Apparently, Liszt also composed a 3rd Piano Concerto, possibly before the first two. This concerto was basically unknown until 1989, but it was identified and assembled from multiple sources by Jay Rosenblatt. It had long been assumed that they were early drafts of Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1, but since Liszt never mentioned a third concerto in his writing, the existence was unknown. That work premiered in 1990, but it remains little known and little played.

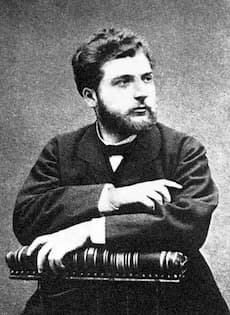

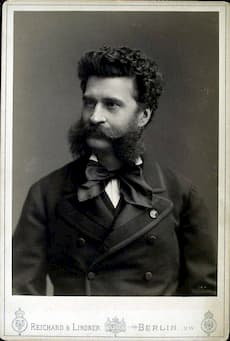

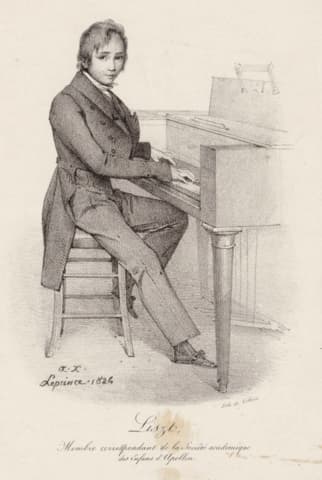

Franz Liszt

Concertos aside, Liszt wrote a number of works for solo piano and orchestra, mostly during his teenage years. In fact, these pieces are probably his first attempts at orchestral writing, combining the forces of the piano and the orchestra. As we celebrate Liszt’s birthday on 22 October, we thought it might be fun to listen to these pieces rarely featured on concert programs today.

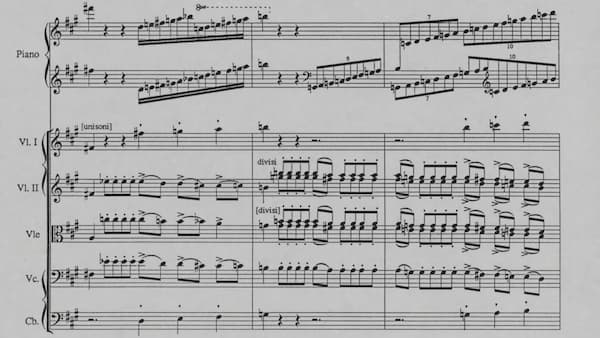

Malédiction, S121/R452

Liszt wrote at least two concerti for piano and orchestra in his teens. However, they were never published, and the manuscripts were presumed lost or ignored. Such is the case with the single-movement concerto for piano and strings known as Malédiction. It was started in 1833, revised in 1840, then forgotten and published only in 1915. Actually, the origins of the work might be traced back to 1827, when sixteen-year-old Liszt played a concerto in London. The great pianist Ignaz Moscheles described it as having “chaotic beauties,” but all traces seem to have been lost.

Liszt did not provide a title for the work, but when the composer received the manuscript from the copyist, he inserted certain descriptive romantic phrases over different sections of the music. The opening theme, which was later taken over in the Années de pèlerinage, is labelled “Malédiction” (Curse), while the second theme area is marked “Orgueil” (Pride).

Liszt would later reuse this theme in his Faust Symphony. A calmer section carries the direction “Pleurs, angoisse” (Tears, anguish), and he identifies the codetta as “Raillerie.” The work is unusual as it features only strings in the orchestra, but as John Lade writes, it is “a remarkable succession mood sketches showing a striking, even unexpected unity in performance.”

Grande Fantaisie Symphonique (on themes from Berlioz Lélio)

The young Liszt

Franz Liszt and Hector Berlioz first met a few months after the July Revolution, when Liszt attended the first performance of the Symphonie fantastique in the company of the composer on December 5 1830. Berlioz and Liszt developed a warm friendship that lasted the better part of 20 years. Berlioz does speak of Liszt with a good deal of affection in his Mémoires, and he clearly regarded him unrivalled as a pianist. However, he was much more guarded about Liszt’s orchestral compositions.

Liszt did fashion a piano transcription of the Symphonie fantastique, and when Berlioz produced the sequel Lélio, for reciting actors, choruses with orchestra, and voices featuring dramatic monologues, Liszt decided to use two themes to construct a large-scale work in two parts. He titled it “Grande Fantaisie Symphonique,” featuring a full orchestra and a piano part fully integrated into the orchestral texture.

For his fantasy, Liszt uses the ballad for tenor and piano Le pêcheur, and the song for baritone, men’s chorus and orchestra called Chanson de brigands. Liszt writes an imaginative introduction before the first expansive melody finally appears as a piano solo. This theme is developed at length in dramatic fashion and into far-reaching tonalities, and a pianistic explosion leads to the “Brigands’ Song.” Here, Liszt preserves the Berlioz orchestration for a couple of measures before the piano takes over. The theme is developed, and new themes, not from Lélio, appear before a reworked reprise concludes a very confident work by the 23-year-old Liszt.

Fantasy on Themes from Beethoven’s “Ruins of Athens”

Franz Liszt met Beethoven at the age of 11 when he was introduced by his teacher Carl Czerny. The young Liszt played a piece of Ries and a fugue by Bach, which Beethoven told him to transpose. Beethoven apparently told him, “You are one of the lucky ones, as it is your destiny to bring joy and delight to many people.” For Liszt, “it was the proudest moment in my life.” It is hardly surprising that Liszt was to become a tireless champion of Beethoven and his music.

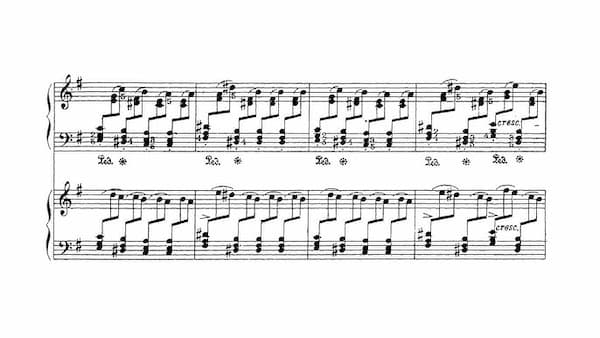

Franz Liszt: Fantasy on Themes from Beethoven’s “Ruins of Athens” music score

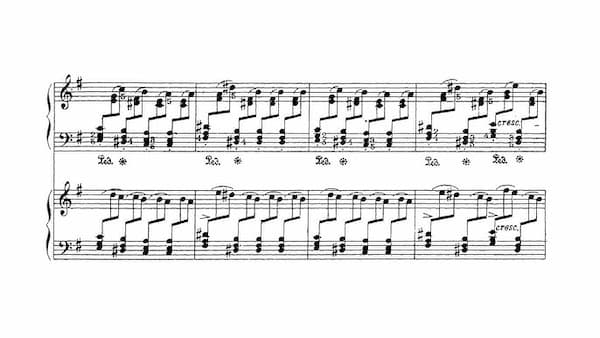

Once Liszt had completed the final revisions for his E-flat Major Concerto, he issued his Fantasy on Beethoven’s the “Ruins of Athens” in three different versions: one for solo piano, one for two pianos, and one for piano and orchestra. All three versions are dedicated to Nikolay Rubinstein, and Liszt extracts three Beethoven themes to fashion his Fantasy.

The introduction, exclusively sounded by the orchestra, uses material from the “March and Chorus” section of the original music blended with Liszt’s own “Capriccio alla turca.” The piano takes the lead in the “Chorus of the Dervishes,” while the final section is based on the famous “Turkish March.” Introduced in a very gentle way, with the orchestration, volume and tempo gradually increasing, the coda resounds the other themes. An annotator writes, “For some inscrutable reason, this excellent work is almost never encountered in concert, a fate which seems to have befallen Beethoven’s original, too.”

Fantasia on Hungarian Folk Melodies

Franz Liszt at around 14-15 years old

During Liszt’s lifetime, his Hungarian Rhapsodies were among his most popular works. Liszt writes, “by using the word Rhapsody, I wanted to describe the fantastical-epical nature I believed I had found therein. Each of these works seems to me to form part of a series of poems in which the unity of national enthusiasm is most striking; it is a kind of enthusiasm which can only belong to a single people, whose soul and innermost feelings it represents.”

Originally written for solo piano, Liszt decided to produce a version for piano and orchestra of his Hungarian Rhapsody No. 14. The structure is based on contrasting Hungarian folk tunes, a slow “lassan,” followed by a rapid “czifra” and a whirling “friska.” These individual sections are not strictly delineated but are subjected to constant permutations and the introduction of elements taken from improvisation.

The primary theme is based on a Hungarian folk song entitled “The battle of Mohács,” a melody that Liszt knew rather well. Interestingly, as in the piano concertos, Liszt returns to the opening theme to conclude the work. As he reported with a good deal of pride, “this way of summarising and rounding off an entire piece at its conclusion is really quite characteristic of me.”

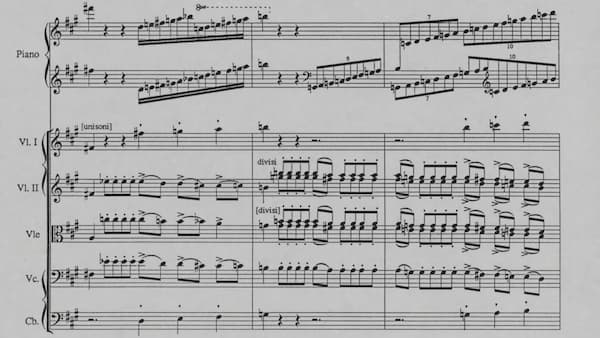

De Profundis

Liszt never completed his 3rd Piano Concerto, and his De profundis “Psaume instrumental” belongs in that unfinished category as well. Composed in 1834/35, this elaborated piano concerto was inspired by Liszt’s friendship with the Abbe Felicite de Lamennais, and his rejection of the right-wing aspects of Roman Catholicism. The text clearly references Psalm 130, but the chant itself was composed by Liszt.

Franz Liszt: De Profundis music score

Out of the depths I have cried unto thee:

O Lord, hear my voice:

Let thine ears be attentive,

to the voice of my supplications.

This early concerto already outlines the way Liszt would subsequently formulate his structural ideas. All sections are presented in a single movement, containing a slow passage, a scherzo and a finale based on the transformation of the material used in previous sections. Liszt treated the orchestra with subtlety and sensitivity, and scholars have found “music of stunning originality and a striking instance of Liszt’s early genius.” Liszt had always wanted to complete the work, but life got in the way. It has since been completed by a number of scholars and performers.

Totentanz

Although Liszt never completed his “Psaume instrumental,” he did recycle the chant melody in his first version of the Totentanz. However, the inspiration for Totentanz (Dance of Death) was probably pictorial rather than literary or musical. In 1839, Liszt and Marie d’Agoult visited Pisa and admired the fresco of the Last Judgement. Liszt might have found additional inspiration in a series of wood engravings by Hans Holbein, which Liszt references in a letter to his son-in-law Hans von Bülow, to whom the work is dedicated.

The work is a series of variations on the “Dies irae” theme which Berlioz had famously used in his Symphonie fantastique to portray the sabbath of the witches. A contemporary critic writes, “Its shuddering, clanking rhythms, its sounds as of dancing bones, are of the weirdest achievement possible.” Liszt achieves astonishing dramatic power interspersed by moments of unexpected peace.” And Béla Bartók wrote, “…the work has such a phantasmagorical, dream-like quality that one feels one is in a world in which the strangest things could happen, and no juxtaposition is too bizarre.”

Totentanz was to be Liszt’s final work for piano and orchestra. Shortly after the premiere, Liszt was ready to join a clerical order, and he was thus known as Abbé Liszt for the remainder of his life. I trust you enjoyed this little excursion into the repertoire for solo piano and orchestra by Franz Liszt, a repertoire that combines the extraordinary accomplishments of his pianism with his visionary imagination as an orchestral composer. Happy Birthday!