It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Friday, November 4, 2022

Yuja Wang: Schumann Piano Concerto in A minor Op. 54 [HD]

Sunday, October 9, 2022

Martha Argerich: Schumann Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54(2022)

Monday, October 3, 2022

Play Always as if in the Presence of a Master

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

Lang Lang masterclass

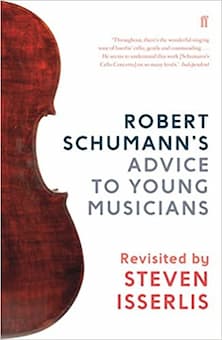

The title of this article is a quote from Robert Schumann’s ‘Advice to Young Musicians’, a cornucopia of practical advice and poetic words of wisdom for young people beginning their musical education, which still has plenty of relevance for musicians of all ages and abilities today.

When we see the word “master” in relation to music, most of us immediately think of the “masterclass”, the private lesson in public where participants submit their playing to the scrutiny of a “master teacher” such as Angela Hewitt or Maxim Vengerov. At one time, such classes were quite terrifying for the participants (I remember watching masterclasses with cellist Paul Tortelier on the TV in the 1970s and 80s and he seemed very fierce!), but in these more enlightened times, the masterclass, sometimes rebranded as “workshop”, has become a valuable forum for critique, support and advice, not only from the “master” but also from active listeners – something private lessons do not offer.

Watching a masterclass, especially with high-level players, is an opportunity to watch artists at work. It reveals what musicians do when they practice and often confirms the huge amounts of time and effort which go into refining music – something which is often forgotten when we see musicians performing. One of the most exciting aspects of the masterclass is witnessing breakthroughs and seeing how just a few words from an experienced master teacher can transform the participant’s playing. It’s an exciting and rewarding experience shared by both performers and observers.

Robert Schumann’s ‘Advice to Young Musicians’

© Amazon

In fact, I don’t believe Schumann was thinking of the masterclass as we know it today in his aphorism, but was actually referring to an attitude of mind which should colour one’s practicing and playing at all times. It is a fact universally acknowledged amongst musicians and music teachers that mindless practice is not only unproductive but also unmusical. But if we play “as if in the presence of a master”, we raise our game. In short, what Schumann is suggesting is that one should always play (and I include “practice” in the word “play”) with all one’s critical and artistic faculties fully alert – mindfully, deeply and beautifully. Repetitive practise is important, for sure, but it should be always be both thoughtful and repetitive – and each repetition should be considered and reflected upon. Taking notice of what one is playing – each phrase, dynamic nuance, subtleties of touch, expression, articulation – will result in more efficient and rewarding practice, leading to the kind of vibrant and authoritative playing one would be happy to present to a master teacher. In effect, one is putting into practice the habits of a master musician; this approach is relevant to from the beginner to the highly advanced player and is one we should carry with us at all times, from the practice room to the performance stage.

For me, Schumann’s comment also suggests one should not fear playing to a master. If you become accustomed to playing with that mindset, what is there to fear?

Wednesday, September 14, 2022

The Coming Joy: Raff’s Ode au Printemps

by Maureen Buja

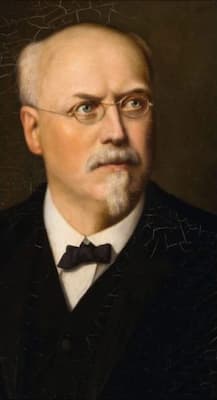

Joachim Raff

Considered during his lifetime the premier symphonist of the day, Joachim Raff (1822-1882) has now virtually vanished from our concert stages. He was encouraged by Mendelssohn and his scores, sent to his publisher by Mendelssohn, got the approval of Robert Schumann in his reviews in his music journal.

Liszt was an admirer and asked Raff to join him in Weimar, where from 1850 to 1856, Raff was part of the Liszt household. Eventually, Raff tired of Liszt’s overbearing personality, but while he was in Weimar, was able to create his own musical voice, poised somewhere between the conservatism of the Mendelssohn / Schumann camp and the revolution of the Liszt / Wagner camp.

Entirely self-taught, his breakthrough came in 1863 when both his First Symphony and a cantata won prizes that brought him to the attention of the concert-going world. He became the founding director of the Hoch Academy in Frankfurt in 1877. The Hoch Academy was important not only for employing Clara SchumannTra but also for holding special music classes just for women. As a composer, he wasn’t merely a symphonist but also wrote operas, choral pieces, chamber music, songs, and, above all, works for the piano.

Tra Nguyen

His 1857 work Ode to Spring, is described as a ‘morceau de concert.’ He wrote it in Wiesbaden, six months after having left the Liszt household in Weimar. He now had musical independence and a fiancée, Doris Genast. The work is dedicated to Betty Schott, the wife of Wagner’s publisher, and she performed it in 1860 under its first title: Frühlingshymne (‘Spring Hymn’), described as a Caprice symphonique. Schott published it in 1862 as Ode au Printemps.

It’s not an ode to Spring having arrived, it’s an ode to the coming of Spring. The opening Largetto is atmospheric before the piano joins with a long cantabile melody. The piano is then joined by a solo cello and then the full orchestra. It is in the Presto section that Spring arrives with its exuberance and energy. A brass fanfare announces the true arrival of the season. The end of the work is calmer, sunlit, and closes with a flourish.

Tuesday, August 16, 2022

Yuja Wang: Schumann Piano Concerto in A minor Op. 54 [HD]

Thursday, June 2, 2022

From Children’s Tales to Scenes from Childhood

by Maureen Buja , Interlude

Robert Schumann, lithograph by Josef Kriehuber, 1839

Originally, Kinderszenen, Op. 15 was to be published together with the 8 Noveletten, Op. 21, as a work called Kindergeschichten (Children’s Tales) but Schmann changed his mind and separated them. In a 1838 letter to Clara when he sent her the pieces, Robert wrote that they were an answer to her comment ‘that sometimes I seemed to you like a child….’ He told her to laugh at the titles but to take their performance seriously: ‘They will amuse you, but you will have to forget yourself as a virtuoso.’

Clara Wieck at the paino

No. 1. Von fremden Landern und Menschen (Of Foreign Lands and People)

No. 2. Curiose Geschichte (A Strange Story)

No. 3. Hasche-Mann (Catch-as-catch-can)

No. 4. Bittendes Kind (Pleading Child)

No. 5. Glückes genug (Happy Enough)

No. 6. Wichtige Begebenheit (An Important Event)

No. 7. Träumerei (Dreaming)

No. 8. Am Camin (By the Fire-side)

No. 9. Ritter vom Steckenpferd (Knight of the Hobby-horse)

No. 10. Fast zu ernst (Almost Too Serious)

No. 11. Furchtenmachen (Frightening)

No. 12. Kind im Einschlummern (Child Falling Asleep)

No. 13. Der Dichter spricht (The Poet Speaks)

But this is a land as observed by an adult and observed from a distance. The opening piece, Of Foreign Lands and People, serves as the key to the work, with its opening theme appearing in various guises throughout the other pieces.

If we listen to the same piece in other hands, we can hear how much interpretation can change the work.

Brendel’s vision seems much more dutiful than the world of the imagination summoned by Argerich.

The best known of the 13 pieces is the middle one: No. 7, Traumerei (Dreaming). Every child who learns to play it thinks he’s gotten a vision into the world of Schumann, but in the hands of a virtuoso, the role of rubato (a slight speeding up and slowing down of the tempo) gives us a much more dreamlike quality to the work.

Overally, the pieces are not technically demanding, but it is the quality of expression and the sensitivity of the performer to that expression that is key. It is important to remember that the titles are not the story, but only an indication meant to guide the performer. When we look at the final piece, No. 13, The Poet Speaks, we can finally see that these Scenes from Childhood are not scenes as seen by a child, but scenes as remembered by ‘The Poet,’ and therein lies the difference.

Monday, May 2, 2022

Robert Schumann: Album of Songs for the Young

by Georg Predota , Interlude

Robert Schumann

For the 7th birthday of his daughter Marie, Robert Schumann compiled a short album of “Little Piano Pieces.” Once he had gotten that process started, Schumann kept adding miniatures to the collection. His wife Clara Schumann wrote in her diary, “The pieces usually given to children at their piano lessons are so bad, that it has occurred to Robert to bring out a collection of such little works himself.” Schumann was on fire and reported to his friend Carl Reinecke, “I cannot remember ever feeling as content as when working on these pieces… I felt as though I were starting to compose all over again!” Schumann composed the 43 pieces of his Album for the Young in barely 2 weeks, but a good many more miniatures have surfaced in various manuscripts but were not included in the published collection. The set is subdivided into two parts, starting with pieces “suitable for younger players,” and concluding with pieces “appropriate for more mature players.” Clara Schumann prepared the final edition and tellingly wrote, “Never play bad compositions, nor even listen to them, unless absolutely obliged to do so.”

The Evening Star

You lovely star,

You shine from afar,

And so I hold you

Dearly in my heart.

How I do love you

So deep in my heart!

Your twinkling eyes

Look ever on me.

So I look to on you,

As you are there or here:

Your friendly eyes

Stand ever before me.

How you nod at me

In peaceful rest!

O lovely little star,

O were I like you!

(Translation © Gary Bachlund)

Robert Schumann: Album of Songs for the Young

Six months later, Clara Schumann was expecting her fifth child, and Robert Schumann followed up his Album for young pianists with one for young singers. The inspiration for his Album of Songs for the Young might well have been pedagogical, as he considered singing a fundamental part of music education. As he recommended in his pamphlet Musical House and Life Rules, “Try, if you also have only a little voice, to sing from the page without the help of the instrument … But if you have a resonant voice, do not hesitate a moment in cultivating it, consider it as the finest gift that heaven bestows on you! He who wants to cultivate a complete musical personality should not only strive for instrumental virtuosity, as on the piano, but should not neglect singing.” In no time, Schumann had composed 25 solos songs and 4 duets, and he wrote to his publishers: “This collection will best express what I had in mind. I have selected poems appropriate to childhood, exclusively from the best poets, and have tried to arrange them in order of difficulty, progressing from the easy and simple to the difficult and complex. At the end comes Mignon, gazing into a more troubled emotional life.”

Butterfly

[Oh] butterfly tell,

Why do you flee me?

Why are you in such haste,

Now far and then near?

Now far and then near,

Now here and then there–

I shall not catch you,

I shall not harm you.

I shall not harm you:

O stay here always!

And I were a little flower,

I would say to you,

I would say to you:

Come, come to me!

I give you my little heart,

How fond I am of you!

(Translation © Sharon Krebs)

Clara and Robert Schumann

Scholars have suggested “for all their apparent simplicity, these songs need to be performed with loving detachment rather than wallowing sentimentality, and the singers who have been most successful with this repertoire are those who have not turned themselves into children.” The Album of Songs for the Young is not simply a loose collection of songs, but it should be considered a genuine cycle. Fundamentally, “it reflects Schumann’s understanding of the formal and substantial development of folksong into something more elaborate, and it also discloses an exemplary exegesis of a phenomenon by way of varied possibilities for interpreting a given poem in a musical setting.” Following the pattern established in his Album for the Young, Schumann divides the song collection into two sections “For the Younger,” and “For the Older.” The first section begins in the world of children and deals with animals, nature, and daily life. We also find songs of the gypsy lads and shepherd boys, as well as the sandman and the ladybird. The second section leads us into a world of wider experiences and feelings, from the pantheism of Goethe’s “Song of Lynceus the Watchman” to the yearning of “Mignon.”

The Sandman

I wear a fine pair of boots

with wondrously soft soles,

I carry a sack upon my back!

Hush, I scamper quickly up the stairs.

And when I enter the chamber

The children are saying their prayers:

Two little grains of my sand

I scatter into their eyes,

Then they sleep the whole night

Watched over by God and the angels.

Two little grains of my sand

I scattered into their eyes:

The good little children should be visited

By a beautiful dream.

Now rapidly and swiftly with my sack and my stick

back down the stairs!

I can no longer stand around idly,

I must still visit many [children] tonight.

You are already nodding off and laughing in your dreams,

And I barely opened my little sack.

(Translation © Sharon Krebs)

Robert Schumann: Album of Songs for the Young, 29 May, 1849

In terms of music, Schumann’s Album of Songs for the Young offers increasing levels of difficulties. In the opening “children’s songs” the melody is primarily supported by simple but delightful harmonic progressions in the piano. The harmonic accompaniment, sophisticated as it well may be, is simply intended to support a young singer. It has been suggested that Schumann here “follows the tradition of pedagogically oriented collections of songs for children from the 18th century, found in a variety of published sources.” These songs can also be performed together in the family circle. Mailied (May Song) has a second voice ad lib, some numbers are for two voices, while Spinnelied (Spinning Song) is for three, and in Weihnachtlied (Christmas Song), with the text attributed to Hans Christian Andersen, at the end a chorus can join in with the refrain ‘Hallelujah, Kind Jesus’ (Alleluia, Child Jesus).”

Christmas Song

When the Christchild was brought to the world,

Who has rescued us from hell,

He lay in a manger in dark night,

Pillowed on straw and hay;

But above the hut there shone the star,

And the ox kissed the foot of the Lord.

Halleluja, Child Jesus!

Take courage, soul that is sick and weary,

Forget your gnawing pains.

A child was born in the city of David

As a comfort for all hearts.

Oh let us go to the little child,

And become children in mind and spirit.

Halleluja, Child Jesus!

(Translation © Sharon Krebs)

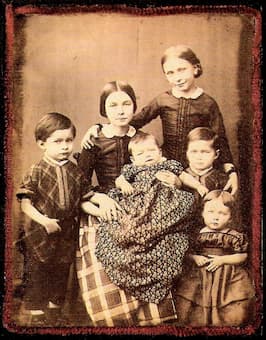

Clara and Robert Schumann’s children

Scholars have suggested that the songs of Schumann’s Album of Songs for the Young hold only a marginal position in musical life today. “For young singers they seem in part overtaxing, but because of their pedagogic aims, on the other hand, they are artistically undervalued by adult singers. The first numbers in particular seem too childish for performance by a concert singer. It may be argued, however, that Schumann’s songs conjure up, not naively but in feeling, the innocent world of childhood.” Aesthetically, they seem close to his piano set “Scenes of Childhood,” which also present idyllic reflections of childhood by adults. That sense of childhood idyll is clearly seen on the title-page of the first edition, which portrays a group of children singing and making music in a paradise of a natural setting “of leafy tendrils with flowers, fruits and nesting birds.”

Watching over children

When good children go to sleep,

Two little angels stand by their beds,

They tuck them in and tuck them up,

And keep a loving eye on them.

But when the children get up,

Both the angels go to sleep,

If the angels’ strength is now not enough,

The good Lord himself keeps watch.

(Translation © Richard Stokes)

Schumann’s Album of Songs for the Young develops from children’s songs to pure art song in the Mörike setting “Er ist’s” (It is Spring).

Spring is here

Spring is floating its blue banner

On the breezes again;

Sweet, well-remembered scents

Drift portentously across the land.

Violets, already dreaming,

Will soon begin to bloom.

Listen, the sound of a harp!

Spring, that must be you!

It’s you I’ve heard!

(Translation © Richard Stokes)

The piano and vocal part are quietly restrained in the first half of the song, possibly suggesting that spring can already be sensed, but that it has not yet arrived. However, after a delicate and light staccato arpeggio imitating the echo of a harp, the “protagonist loudly bursts forth with recognition of the season’s entrance; here, the vocal line simultaneously reaches its highest notes and its first forte crescendo within just two demanding measures.” The composer repeats segments of the text several times, varying each occurrence, especially in terms of dynamics, to emphasize the protagonist’s elation.

Critics have suggested, “Mörike-lovers may consider this song a witless travesty of a beautiful poem.” However, the music is certainly charming and effective, and Schumann has left the innocence of his early songs in this set behind and the music has “grown into the dancing pulse of a girl’s first love song.” Until recently, it has been fashionable to consider the songs of 1849 a decline. “Schumann never again reached or even approached the level of his 1840 masterpieces” a scholar writes. “Other composers of comparable stature are believed to mature in their music; Schumann appears to deteriorate. A favoured explanation is mental illness…and the musical evidence seems to support a theory of progressive disorder from 1849 onward. And while Schumann is still a fine songwriter in 1849, he is no longer a great one. Sometimes, as in Goethe’s text from Faust, he treats great poetry rather cavalierly.”

Song of Lynceus the Watchman

I am born for seeing,

Employed to watch,

Sworn to the tower,

I delight in the world.

I see what is far,

I see what is near,

The moon and the stars,

The wood and the deer.

In all these I see

Eternal beauty,

And as it has pleased me,

I’m content with myself.

O happy eyes,

Whatever you have seen,

Let it be as it may,

How fair it has been!

(Translation © Richard Stokes)

Robert Schumann: Lieder-Album fur die Jugend, Op. 79 – No. 24. Spinnerlied (Christina Landshamer, soprano; Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Andreas Burkhart, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

Robert Schumann: Lieder-Album fur die Jugend, Op. 79 – No. 27. Lied Lynceus des Türmers (Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Gerold Huber, piano)

Schumann: Album of Songs for the Young – Mignon

It has been said that Goethe’s character “Mignon” beautifully embodied the virtues of Romanticism. “From her simplicity, to her unbreakable loyalty and strength of emotions, she simultaneously embodies youthful innocence and mature longing, helplessness as an abused child and an ambiguous relationship with her protector… She gave voice to those in society who were otherwise ignored or forgotten.” Schumann composed “Mignon” to conclude his Album of Songs for the Young in the summer of 1849 amidst the uproar and danger of the Dresden uprising.” In his reading of the poetry and his musical setting there is no audible suggestion of decline. It might be somewhat taxing for untrained voices, as the melodic line is disjunct and widely spaced. In addition, the phrasing of the vocal lines and their interlinking with the piano part certainly calls for trained interpreters. Assumed mental deterioration aside, Schuman thought highly enough of his “Mignon” setting to place it at the head of his “Songs of Wilhem Meister,” Op. 98a.

Mignon

Do you know the land where the lemons blossom,

Where oranges grow golden among dark leaves,

A gentle wind drifts from the blue sky,

The myrtle stands silent, the laurel tall,

Do you know it?

It is there, it is there

I long to go with you, my love.

Do you know the house? Columns support its roof,

Its great hall gleams, its apartments shimmer,

And marble statues stand and stare at me:

What have they done to you, poor child?

Do you know it?

It is there, it is there

I long to go with you, my protector.

Do you know the mountain and its cloudy path?

The mule seeks its way through the mist,

Caverns house the dragons’ ancient brood;

The rock falls sheer, the torrent over it,

Do you know it?

It is there, it is there

Our pathway lies! O father, let us go!

(Translation © Richard Stokes)

Friday, November 5, 2021

Robert Schumann: Paradise and the Peri, Op. 50

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Robert Schumann © Wikipedia

When Robert Schumann premiered his secular oratorio Das Paradies und die Peri, Op. 50 (Paradise and the Peri) in December 1843 in Leipzig, the composer was instantly catapulted from provincial to international fame. In the first decade after the composition, the Peri was performed more than fifty times. Schumann even called it his “greatest work,” and his wife Clara suggested, “It seems to me the most magnificent he has written yet.”

Although the work was a resounding success with audiences and critics alike, it quickly disappeared from the repertoire and has been unable to gain a foothold in the modern concert hall. A number of commentators have wrongly located the primary reason for the work’s neglect in the “flowery, Eastern-inspired verbiage of the libretto.” The subject matter is loosely based on one of the four lengthy poems from Thomas Moore’s oriental epic the Lalla Rookh. Originating in Persian mythology, the text strongly resonates with contemporary enthusiasm for oriental impressions that is reflected in light fiction as well as serious literature.

The story centers on the heroine Peri, who is seeking admission into paradise, a realm from which she has been excluded owing to her mixed descent from the union of a fallen angel and a mortal. Peri can enter the heavenly pastures only if she is able to render “the heaven’s dearest gift.” To gain admission, Peri captures the last drop of blood of a young freedom fighter in India, and in Egypt she catches the last breath of a girl who sacrifices herself for her plague-ridden lover. Both gifts, however, are not sufficient. Only the tear of a Syrian criminal, shed in remorse at the sight of a praying child, finally opens the gates of heaven. Richard Wagner enthusiastically wrote to Schumann in 1843, “I do not only know this wonderful poem, it has also been passing through my musical senses; but I found no form with which to reproduce the poem, and therefore I now wish you the luck to have found the right one.”

The work is clearly the product of Schumann’s ever-fertile interest in literature and allegory. Above all, Schumann was looking to create an oratorio “not for the chapel, but for merry people.” In a musical sense, he blended elements from the oratorio, opera and song. Internally, the work is held together by lyrical quasi-recitative that propels the narrative portions of the text. Since it contains a number of memorable tunes, Schumann was quickly accused of pandering to popular taste. But it was not the choice of text or Schumann’s musical treatment that plunged the work into obscurity. Rather, it all had to do with a subtle change in the inner constitution of concert life. While church music is primarily sustained by the institution, secular non-theatrical music was aligned with notions of education, culture and good breeding. The educated classes in the 19th century extended from the lesser nobility to academics and the working middle classes. Compositions for mixed chorus represented the educated classes, and choral societies formed throughout Europe that would perform at specific times during the year in large musical festivals. Since secular vocal music was closely linked with the spirit and institution of the public concert, it only took some minor changes in social conventions and attitudes to make the entire repertory disappear into oblivion. Maybe the early 21st century is once again sensing the need for a closer connection between the public concert and the educated classes. Whatever the case may be, it is decidedly satisfying to witness the revival of this once highly popular secular choral repertory.

The work is clearly the product of Schumann’s ever-fertile interest in literature and allegory. Above all, Schumann was looking to create an oratorio “not for the chapel, but for merry people.” In a musical sense, he blended elements from the oratorio, opera and song. Internally, the work is held together by lyrical quasi-recitative that propels the narrative portions of the text. Since it contains a number of memorable tunes, Schumann was quickly accused of pandering to popular taste. But it was not the choice of text or Schumann’s musical treatment that plunged the work into obscurity. Rather, it all had to do with a subtle change in the inner constitution of concert life. While church music is primarily sustained by the institution, secular non-theatrical music was aligned with notions of education, culture and good breeding. The educated classes in the 19th century extended from the lesser nobility to academics and the working middle classes. Compositions for mixed chorus represented the educated classes, and choral societies formed throughout Europe that would perform at specific times during the year in large musical festivals. Since secular vocal music was closely linked with the spirit and institution of the public concert, it only took some minor changes in social conventions and attitudes to make the entire repertory disappear into oblivion. Maybe the early 21st century is once again sensing the need for a closer connection between the public concert and the educated classes. Whatever the case may be, it is decidedly satisfying to witness the revival of this once highly popular secular choral repertory.

Monday, April 5, 2021

Clara Schumann - Her Music and Her Life

Clara Schumann née Clara Wieck (1819 – 1896)

Biography

From an early age Clara's prodigious talent at the piano was esteemed throughout Europe. Her talent at the keyboard attracted fellow composer Robert Schumann, and the pair married in 1840. Clara also shared many years of close friendship with Brahms, who said she inspired all his best melodies.

Clara continued to perform throughout her life, championing many works by her husband and Brahms, but her skills as a composer were never fully realized. Balancing her husband's mental instability, the pressures of a solo career, and a family of eight children put pressure on her time, but she still managed to create many important works: her Piano Concerto, Piano Trio and songs set her apart as one of the most talented - if not one of the most overlooked - composers of the era.

Did you know?

Clara was unsure if she should continue to write music because she was a woman. She said: "A woman must not desire to compose — there has never yet been one able to do it. Should I expect to be the one?"