Discovering the 'Paris of Negro' through the Rondalla

Music of the Philippines (Filipino: Himig ng Pilipinas) include musical performance arts in the Philippines or by Filipinos composed in various genres and styles. The compositions are often a mixture of different Asian, Spanish, Latin American, American, and indigenous influences.Notable folk song composers include the National Artist for Music Lucio San Pedro, who composed the famous "Sa Ugoy ng Duyan" that recalls the loving touch of a mother to her child. Another composer, the National Artist for Music Antonino Buenaventura, is notable for notating folk songs and dances. Buenaventura composed the music for "Pandanggo sa Ilaw".

By: CORAZON CANAVE-DIOQUINO

Philippine Music underwent another transformation with the coming of the Americans. The three mainstreams of music during this post-colonial period include classical music, semi-classical music and popular music.

Classical Music

In the newly established public school system, music was included in the curriculum at the elementary and later at the high school levels. At the tertiary level, music conservatories and colleges were established. The earliest such schools were St. Scholastica’s College (1906) and the University of the Philippines Conservatory of Music (1916). In the 1930’s, two private music schools were established in Manila: The Academy of Music (1930) under Alexander Lippay and the Manila Conservatory of Music (1934) under Rodolfo Cornejo. Both these schools however did not last beyond a few years. Subsequently, other schools with strong music departments emerged at the University of Sto. Tomas, Silliman University, Centro Escolar Univesity, Santa Isabel, St. Paul College and the Philippine Women’s University.

The graduates from these institutions included present-day composers and performers. Composers produced works utilizing the western idiom and forms: symphonies, chamber works, concertos, solo instrumental works, choral works, solo vocal works. The leading figures of the first generation of composers were Nicanor Abelardo, Francisco Santiago, Antonio Molina, and Juan Hernandez. Classical works written from the 1940’s to the 1970’s were mostly contributed by the first members of the League of Filipino Composers founded in 1955. The majority of these compositions were written in the style of the late 19th century European classical music. These included works by Rosalina Abejo, Alfredo Buenaventura, Antonio Buenaventura, Rodolfo Cornejo, Felipe Padilla de Leon, Hilarion Rubio, Lucino Sacramento, Lucio San Pedro, Rosendo Santos, Amada Santos-Ocampo, and Ramon Tapales.

After studies abroad, modern methods of composition were employed by Eliseo Pajaro and Lucresia Kasilag. Both were strongly influenced by American neoclassicism. Jose Maceda is considered the first legitimate Filipino avant-garde composer. He was the first Filipino composer to succeed in liberating Philippine musical expression from the colonial European mould of symphonies, sonatas, and concertos. Among the younger generation of composers, the first to respond to the challenges of new music were Francisco Feliciano and Ramon Santos. A still younger set of composers, all students of Ramon P. Santos includes Josefino Toledo, Ruben Federizon, Verne de la Pena, Arlene Chongson, and Jonas Baes. Since the 1950’s to the present, the trend of serious musical compositions in the Philippines has been towards a synthesis of traditional concepts of structure, of time, of space, of melody, of performance medium with the new and experimental techniques.

In the performance field , some notable Filipino artists include Jovita Fuentes, Isang Tapales, Ramon Tapales, Dalisay Aldaba, Conchita Gaston, Mercedes Matias, Federico Elizalde, Luis Valencia, Oscar Yatco, Benjamin Tupas, Nena del Rosario Villanueva, Jose Contreras, Fides Asencio Cuyugan, Reynaldo Reyes, Jose Maceda, Ernesto Vallejo, Sergio Esmilla, Carmencita Lozada, Basilio Manalo, Evelyn Mandac, Aurelio Estanislao and Cecile Licad.

Outstanding groups include the Manila Symphony Orchestra, the Filipino Youth Symphony Orchestra, the U.P. Symphony Orchestra, the Manila Concert Orchestra, the Quezon City Philharmonic Orchestra, the Artists’ Guild of the Philippines, the Philippine Choral Society, the U.P. Madrigal Singers, the U.P. Concert Chorus among others.

Semi-Classical Music

The semi-classical repertoire includes stylized folk songs, music for theater, songs and ballads, and various types of instrumental music. An awakened interest in field work produced a body of folk songs from the different regions of the Philippines. These were written in Western notation, often utilizing western harmonies. Instrumental and vocal arrangements of the songs were published and used as educational materials in schools.

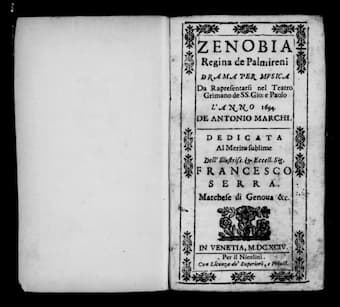

The native sarswela in the vernacular, an outgrowth of the Spanish zarzuela introduced in1879, appeared by 1900. Composers who wrote music for these dramas included Bonifacio Abdon, Alejo Carluen, Gavino Carluen, Jose Estella, Fulgencio Tolentino, Juan Hernandez, Francisco Buencamino, Leon Ignacio, and Francisco Santiago. As a general rule sarswela composers functioned as conductors of the orchestra. Often they were instrumental performers of note in their own right. Many taught in schools or gave private lessons in homes. They also appeared in large public music concerts as well as in smaller gatherings where music programs formed the main attraction of informal and semi-formal occasions.

The sarswela solo songs became models for the classical kundiman and the lighter type of love songs and ballads used in radio and in the cinema. These songs were further popularized in the 1950’s with the advent of the recording industry, particularly the Villar Recording Company. It gave rise to the unprecedented popularity , not only of the music, but also of the performers. Outstanding instrumental groups included the Juan Silos Rondalla, the Leopoldo Silos Orchestra, and the Mabuhay Recording band. Top artists were Sylvia La Torre, Ruben Tagalog, Cely Bautista, Raye Lucero, Diomedes Maturan, Pilita Corales, Cenon Lagman, Ric Manrique, and Nora Aunor. Initially the songs were written by Abelardo, Santiago, Buencamino, later joined by Mike Velarde, Constancio de Guzman, Josefino Cenizal, Juan Silos, Manuel Velez, Leopoldo Silos, Simplicio Suarez, Minggoy Lopez, Santiago Suarez, Restie Umali, Antonio Maiquez, and Ernani Cuenco. A favorite lyricist of these major songwriters was Levi Celerio.

In the field of semi-classical instrumental music, the band stands out. The tradition of village and town bands that proliferated during the Spanish times continued. By the turn of the century, band performances in Manila which took place at the Luneta, the Plaza Mayor, and the Calzada were highly praised for their impeccable performances. Travelogues written at this time echo the same sentiment- that nowhere had they heard such fine performances. Until today, the band tradition goes on. Marches, concert overtures, concertant pieces, tone poems, and even symphonies have been written for band. Composers of band music include Alfredo Buenaventura, Antonio Buenaventura, Francisco Feliciano, Felipe Padilla de Leon, Eliseo Pajaro, Hilarion Rubio, Lucino Sacramento, Lucio San Pedro and Rosendo Santos.

A popular medium for light classical muse is the rondalla. Its repertoire consists mainly of native folk tunes, ballroom music as well as arrangements of classical pieces such as opera overtures. Bayani de Leon and Jerry Dadap have written more serious music for the rondalla.

Popular Music

The third mainstream of music during the 20th century is popular music. This genre includes Pinoy Ballads, Pinoy Rock, Manila Sound, Pinoy Disco, Pinoy Folk, Mainstream Jazz, Pinoy Jazz Fusion, Pinoy Rap, Ethnic Pop, and novelty songs.

About the Author:

Corazon Canave-Dioquino musicologist, is a professor at the University of the Philippines, College of Music where she has taught for the past 42 years.She is actively involved in the collection and archiving of musical Filipiniana at the UP Center for Ethnomusicology at Diliman, Quezon City.

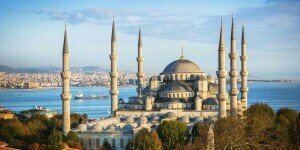

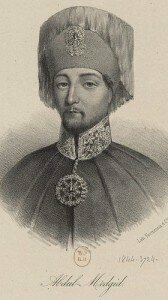

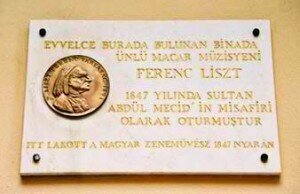

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.