by Georg Predota, Interlude

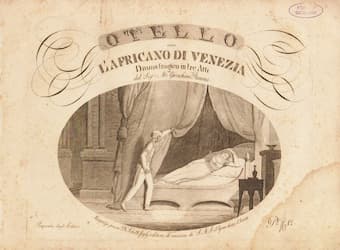

Rossini’s Otello

We celebrate Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) as one of the most successful and popular operatic composers of his time. And although you might never have actually seen or heard a complete Rossini opera, I am sure you know a good many of his overtures. In fact, the overtures have long been staples of the orchestral repertory and much more frequently performed than the operas to which they belong. It is a curious situation in that the reputation of his dramas has never equaled the sweetness “of their melodies, the richness of their harmonies, the brilliance of their orchestration, and the power of their rhythms.” We do know that almost all of his overtures make use of musical elements and melodies that appear somewhere in the opera, which begs the question if Rossini composed the overture before or after he had completed the opera? According to legend, that’s exactly the question a young composer asked Rossini, who described six different ways of composing overtures. Rossini apparently said, “I composed the overture to Otello in a little room in which that most ferocious of all managers, Barbaja, shut me up with a dish of macaroni and told me that he would let me out only after the last note of the overture had been written.” As a point of reference, Otello was first performed in Naples at the Teatro del Fondo in 1816, and the notorious Barbaja was indeed involved. As far as the overture goes, this one was clearly written after the opera had been completed.

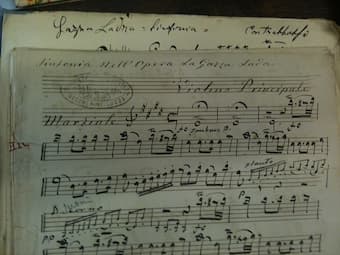

Rossini’s La Gazza Ladra

The same process was apparently at work with the overture to La Gazza Ladra (The Thieving Magpie). Rossini reports that he “wrote the overture to Gazza Ladra, on the very day of the first performance of the opera in the wings of the Scala Theatre in Milan. The manager had put me under the guard of four stagehands who were ordered to throw down the music pages, sheet by sheet, to copyist seated below. As the manuscript was copied, it was sent page by page to the conductor who then rehearsed the music. If I had failed to keep the production going fast, my guards were instructed to throw me in person down to the copyists.” Fortunately, Rossini was able to keep up, and therefore managed to witness the huge success of the opera. Rossini himself was thrilled by his opera and a few days after the première wrote in an excited letter to his mother “that it was so full of music that one could make three or four operas from it,” and that it was “the most beautiful music I have written so far.”

Rossini’s The Barber of Seville

Rossini’s opera buffa The Barber of Seville is primarily known today for its rousing overture. However, the premiere on 20 February 1816 at the Teatro Argentina in Rome was a disaster! The next day Rossini wrote to his mother, “Last night my opera was staged and it was solemnly booed, what mad, what extraordinary things are to be seen in this country. I will tell you that in the midst of it all the music is very fine and already people are talking about its second evening when the music will be heard, something that did not happen last night, from the beginning to the end without the constant noise accompanying the whole performance.” Rossini was entirely correct about the second performance, as it was an unqualified triumph. But how did Rossini compose the famous overture? He writes, “I made my task easier in the case of the overture to the Barber of Seville, which I left unwritten; instead I made use of the overture to my opera Elisabetta, which is a very serious opera, whereas the Barber of Seville is a comic opera.” In fact, the overture is actually twice re-cycled as he had originally written it for the opera Aureliano in Palmira of 1813.

Rossini’s Le Comte Ory

Rossini’s fourth opera for Paris, Le Comte Ory, was first staged at the Paris Opéra in August 1828. Set in thirteenth-century France, the opera deals with the attempts of Count Ory to woo the Countess Adèle, whose husband is away on a crusade. There is much disguising—including hermits and nuns—and everybody manages to run away just before the husband of the Countess returns. The “Introduction” is well matched to the plot, its outer sections suggesting the Count’s cunning exploits, with a martial passage at its heart, the returning opening section ending in the plucked notes of the strings.” How did Rossini go about composing the “Introduction?” According to the composer, “I composed the overture to the Comte Orly while fishing in the company of a Spanish musician who the whole time talked incessantly about the Spanish political situation.” Really doesn’t tell us much about the creative process, but it’s a nice anecdote nevertheless.

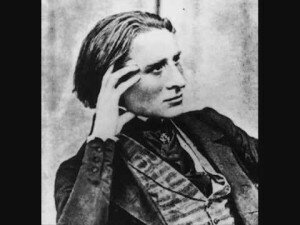

Rossini’s William Tell

When we talk about instrumental favorites in contemporary concert halls, we invariably stumble across the overture to William Tell. While the opera itself has been largely forgotten, the overture owns much of its popularity to varied incorporations within expressions of popular culture. Let’s not be deceived, however, because the popular appeal of Rossini’s William Tell Overture was instantaneous. It was immediately published independently from the opera, and Franz Liszt promptly fashioned his famous piano transcription. Rossini tells us that he “composed the overture to William Tell in the lodgings on the Boulevard Montmartre filled night and day with a crowd of people smoking, drinking, talking, singing, and bellowing in my ears while I was laboring on the music.”

Rossini’s Mosè in Egitto

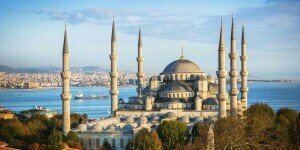

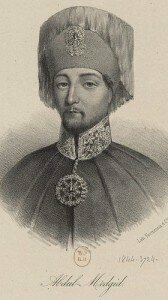

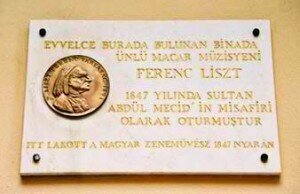

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.