by Georg Predota, Interlude

Bach’s St. Matthew Passion

In both works, the text is capable of telling the story all on its own, but Bach adds multiple layers of musical meaning that make it possible to enjoy the music on a number of levels. Bach’s music makes the text and the story come alive, and the compositional complexity and theological depth trigger a wide range of profound emotional responses.

As the Passions are sacred oratorios performed in churches and concert halls, they forgo some important visual elements associated with opera. There are no costumes or scenery, and there is no action. So what happens when one of the single greatest masterpieces of Western sacred music combines Bach’s powerful music and the passion narrative with spellbinding dance performances?John Neumeier

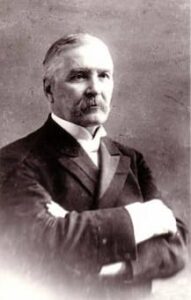

John Neumeier

Transforming the gospel into dance and expressing religious experiences and convictions, has been the life work of the American ballet dancer, choreographer, and director John Neumeier. After a career as a ballet dancer in the United States, Neumeier became director of the Frankfurt Ballet, and subsequently the chief choreographer at the Hamburg Ballet in 1973. He has choreographed more than 170 works, including many evening-length narrative ballets.

John Neumeier’s St. Matthew Passion

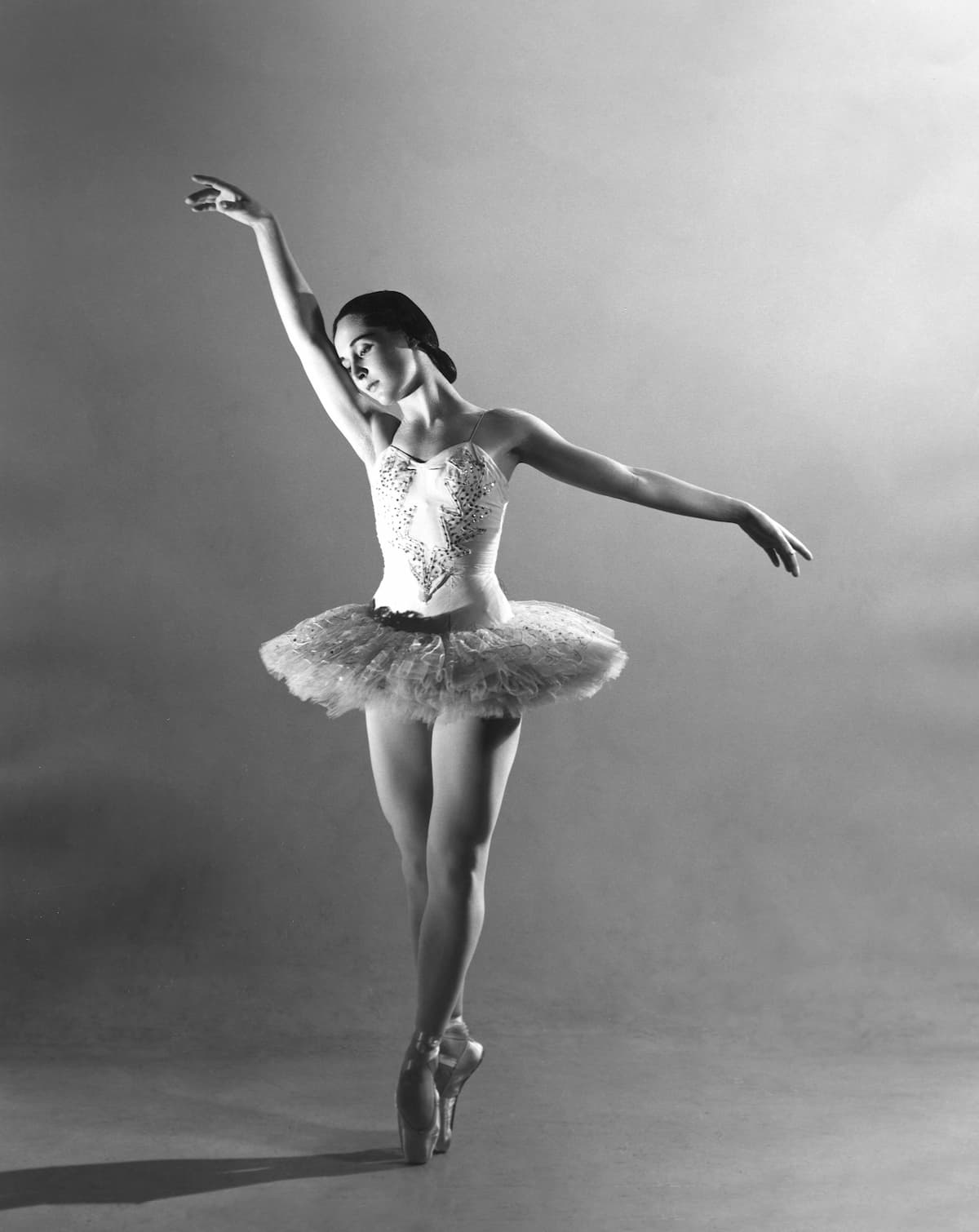

Neumeier premiered his St Matthew Passion as a medieval passion play in a Hamburg church before taking it to the Hamburg Opera House. Neumeier’s dancers, dressed in white, embody Bach’s human Passion, with the audience invited to physically and spiritually experience the drama of struggle and redemption. Each dancer expresses grief, doubt, and even aggression, which adds a powerful visual dimension and physical reality to the allegory. Neumeier focuses on the awe-inspiring complexity and universal appeal of Bach’s St Matthew Passion into a profoundly moving experience.

Friederike Rademann

The German choral conductor and teacher Helmuth Rilling is best known for his performances of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries. He was the first conductor to have twice prepared and recorded the complete choral works of J. S. Bach on modern instruments. Rilling was a student of Leonard Bernstein in New York, and in 1954 he founded the internationally recognized Gächinger Kantorei, which joined forces with the Bach Collegium Stuttgart.

The Gächinger Kantorei is still the ensemble of the International Bach Academy in Stuttgart, and it currently combines a baroque orchestra and a selected number of choristers. The ensemble is under the direction of Hans-Christoph Rademann, and his wife Friederike was a solo dancer at the Semperoper in Dresden. She has devoted herself to expressive dance and developed choreographies for a number of works by Chopin, Ravel, Schumann, and Bach, including the St. Matthew Passion. Her choreography includes the participation of one hundred schoolchildren, who connect and experience Bach’s monumental work as an artistic form of self-expression.

Gloria Contreras

Gloria Contreras

Born in Mexico City, the dancer and choreographer Gloria Contreras was a student of George Balanchine. She taught choreography at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and was director and founder of its choreography workshop. For Contreras, dancing was much more than just a profession, it is “a way of life that teaches a greater understanding of life itself.” Contreras adopted the neo-classical choreographic style of Balanchine, and utilized the music of Mexican composers in her work. However, she also left us a moving choreography of the St Matthew Passion.

Kamea Dance Company

The Passion settings of Bach continue to inspire contemporary ballet productions. One such interpretation, combining music with virtuosic dance movements, comes from the Kamea Dance Company from Be’er Sheva, in southern Israel and the choreographer Tamir Ginz. The title “Matthew Passion 2727” asks the question of what will have happened to this work 1000 years after its premiere in 1727, and what will happen on the way there. Ginz does not translate doctrines, world views, or political statements, but expresses universal human experiences such as suffering and envy, grief and betrayal.