By Hermione Lai, Interlude

Pandemics come and pandemics go, but Easter will surely return every year. For many Christians around the world this is the most important holiday of the year. It commemorates the Passion of Christ, starting with the Last Supper and culminating with the crucifixion and death of Jesus. But above all, it celebrates the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The time around Easter, in many cultures and in different parts of the world is connected with a sense of renewal. Hurrah, Spring is finally coming!

Pandemics come and pandemics go, but Easter will surely return every year. For many Christians around the world this is the most important holiday of the year. It commemorates the Passion of Christ, starting with the Last Supper and culminating with the crucifixion and death of Jesus. But above all, it celebrates the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The time around Easter, in many cultures and in different parts of the world is connected with a sense of renewal. Hurrah, Spring is finally coming!

Here Comes Peter Cottontail

“Here comes Peter Cottontail”

Easter is not just a religious or nature ritual, but it is also connected with some very fun traditions for children and for those young at heart. And Easter wouldn’t be Easter without some beautiful, popular, uplifting and joyful music. So here comes my personal playlist of the most fun classical songs and popular tunes for Easter. Let’s get started with the long-eared and short-tailed creature who delivers decorated eggs to well-behaved children on Easter Sunday. Yes, I am talking about the Easter Bunny. You won’t find him mentioned in the bible, but Peter Cottontail is definitely a hugely popular Easter tradition.

Duke Ellington: Cotton Tail (Dee Dee Bridgewater)

Duke Ellington

The young Easter Bunny Peter Cottontail lives in April Valley together with his fellow Easter Bunnies. They make Easter candies, sew bonnets, and they decorate and deliver Easter eggs. But trouble starts brewing when Peter Cottontail, who is somewhat unreliable and gossipy, is supposed to be appointed Chief Easter Bunny. An evil rabbit named January Q. Irontail also wants the job, but his motivation is a little different. He wants to ruin Easter for children as revenge for a child roller-skating over his tail. Now he has to wear an artificial tail, and he is not a happy bunny. After much intrigue, scheming, and treachery, Irontail does become the new Chief Easter Bunny. He quickly passes various laws to make Easter a disaster. Eggs have to be painted brown and gray, candy sculptors become tarantulas and octopuses, and instead of Easter bonnets, he orders that Easter rubber boots be made. Of course, things do work out in the end, and Cottontail, all reformed and reliable becomes the official Chief Easter Bunny.

Peter Rabbit

The animated television special of Peter Cottontail dates from 1971, but the character of Peter Rabbit has a long tradition in children’s literature. Beatrix Potter first introduced Peter Rabbit in 1902. It became a huge hit, and she wrote five more books on the subject. “Cottontail” also became the inspiration for the great American composer, pianist and jazz orchestra leader Duke Ellington. When he returned to the US after a successful tour of Europe in 1940, he composed the jazz standard “Cotton Tail.” For jazz aficionados the tune “foreshadows bebop in the rhythmic inflections and melody line.” Jon Hendrick wrote the lyrics accompanying the tune based on the familiar Peter Rabbit fairytale. Personally, I really love the scat tribute to Ella Fitzgerald performed by Dee Dee Bridgewater, as her voice skips and hops across the musical landscape.

Philip Henrik Johnsen: Church Music-Easter Sunday 1757 “Allegro”

Hinrich Philip Johnsen

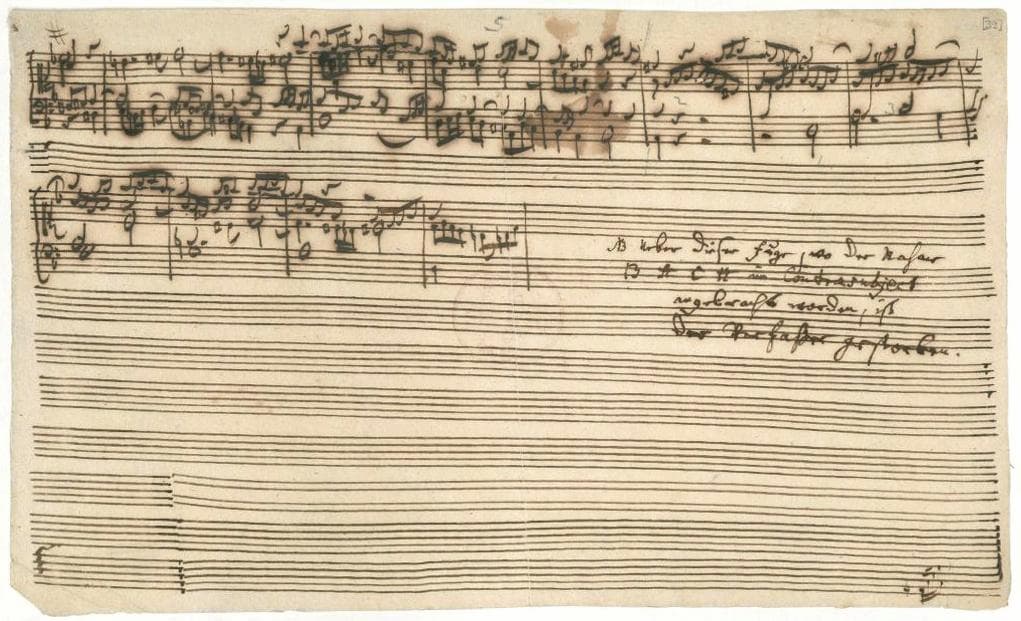

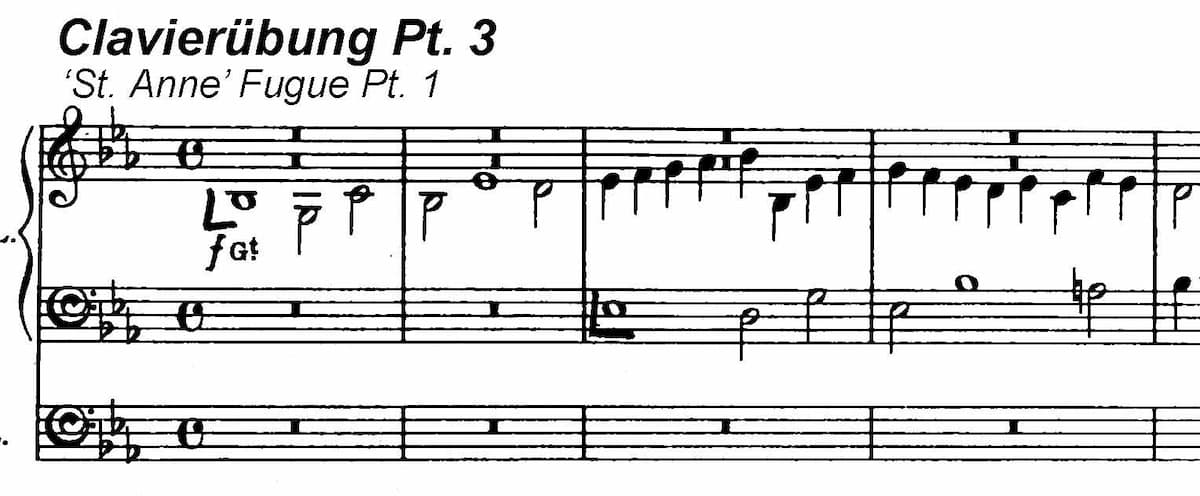

Our next Easter selection takes us to a completely different time and place. The time is the mid-18th century, and the place is Stockholm in Sweden. There had been a bit of trouble deciding on the royal succession, and in the end Adolf Fredrik, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp was elected to the throne of Sweden. The Duke had to pick up his entire household for his move to Stockholm, and he brought his own musicians along. That included a young clavier player named Hinrich Philip Johnsen (1717-1779). He probably hailed from Germany, and he was regarded as a prominent contrapuntist and organ improviser. He composed some delightful and cheerful music for the Easter Sunday service in 1757. The reason we know that it was composed in 1757 is because the composer put the date in the title. The music is very cheerful indeed, and even though the composer is not a household name, it’s a really fun Classical Song for Easter.

Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov: Russian Easter Festival, Op. 36

Russian Easter Festival

Everybody has his or her favorite Easter traditions and memories. The Russian composer Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov remembers the celebration of Easter “as a large gathering of people from every walk of life, with several popes conducting cathedral service… the old liturgical chants and nearby monastery bells ringing out.” In 1887/88 he decided to musically encode his childhood memories, growing up in Tikhvin, in Novgorod province. The orchestra was Rimsky-Korsakov’s instrument, and he composed a brilliant and wonderful score. As he wrote, “I want to reproduce the legendary and heathen aspect of the holiday, and the transition from the solemnity and mystery of the evening of Passion Saturday to the unbridled pagan-religious celebrations of Easter Sunday morning.” You can hear all the excitement of the crowds in that beautiful and fun Classical Song for Easter.

Vally Weigl, wife of Karl Weigl © Weigl Foundation

Karl Weigl: 6 Children Songs, No. 4 “To the Easter Bunny”

Karl Weigl was born in Vienna in February 1881. He showed some exceptional musical talent and his parents sent him for private lessons with Alexander Zemlinsky. From his very beginnings as a composer, it became clear that he had a passion for vocal music. His settings of “Six Children’s Songs” to poems by his second wife Vally date from between 1932-1944. They are written in English because Weigl and his family had to flee to the United States when Hitler annexed Austria in 1938. Weigl had a gift for melodic invention, “as well as simple onomatopoeic devices such as the hopping appoggiaturas in his “To the Easter Bunny.” It’s all about the Easter Bunny delivering his brightly-colored Easter eggs. What a fun and hopping Classical song for Easter.

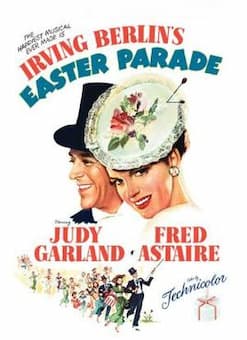

Irving Berlin: Easter Parade

Easter Parade

Easter Parades are said to date back to the early days of Christianity. But they really got going in New York City in the mid-1800s. It was an entirely social event. After the upper crust of society attended Easter services at various churches alongside Fifth Avenue, they strolled outside to show off their new spring outfits and hats. They soon attracted ordinary onlookers wanting to see what the rich and famous were up to, and the tradition of the Easter parade was born. It was highly popular during the mid-20th century, and it even inspired the very popular film “Easter Parade” in 1948. Starring Fred Astaire and Judy Garland, the music was composed by Irving Berlin. Plenty of popular tunes for Easter in that hit production.

Irving Berlin: Easter Parade (MGM Studio Orchestra; Johnny Green, cond.; Roger Edens, piano; Betty Rome, vocals; Blanche Arnaud, vocals; Camilla Holliday, vocals; Fred Astaire, vocals; Gene Curtsinger, vocals; Loolie Jane Norman, soprano; Misses Doxie, vocals; Mel-Tones, vocals; Judy Garland, vocals; Peter Lawford, vocals; Ann Miller, vocals; Dick Beavers, vocals; Clinton Sundberg, vocals; The Lyttle Sisters, choir; Eadie Griffith, piano; Rack Goodwin, piano; MGM Studio Chorus, choir)

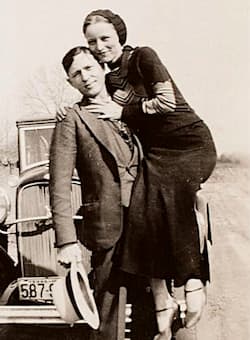

Bonnie and Clyde

Thomas Newman: The Highwaymen, “Easter Morning”

Talking about films, in 2019 Kevin Costner and Woody Harrelson starred in the period crime drama “The Highwaymen”. Essentially, it’s the famed story of the notorious outlaws Bonnie and Clyde, and includes a haunting track detailing some sad events on “Easter Morning.”

Andrew Lloyd Webber: Jesus Christ Superstar, “I don’t know how to love him”

Jesus Christ Superstar © Pamela Raith

Andrew Lloyd Webber is called “the most commercially successful composer in history.” Several of his musicals have run for more than a decade in the West End and on Broadway, and surely you know such hit songs as “The Music of the Night” from The Phantom of the Opera, “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” from Evita, and “Memory” from Cats. One of his earlier and rather controversial projects was the 1970 rock opera “Jesus Christ Superstar.” The story is loosely based on the accounts of the last week of Jesus’ life, and it focuses on the personal psychology of the characters. Audiences were rather shocked by the controversial portrayals of Mary Magdalene, and her unrequited love for Jesus. “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” presents her personal confusion in understanding her attraction to Jesus. This gorgeous tune became hugely popular, and it stormed the pop hit charts.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: “Fantaisie tableaux,” Suite No. 1, Op. 5, No. 4 “Pâques (Easter)”

Rachmaninoff, 1901

As a boy, Sergei Rachmaninoff was frequently taking to Russian Orthodox Church services by his grandmother. He was absolutely enchanted by the rituals, and the sounds of church bells and liturgical chants never left him. His Suite No. 1 for two pianos dates from the summer of 1893, and as he explained, “it consists of a series of musical pictures.” Maybe, these musical pictures are based on poetic excerpts, and the work is dedicated to Tchaikovsky. The final tone picture is called Pâques (Easter), and it takes us back to Rachmaninoff’s childhood and the beautiful ringing of bells. For me personally, it is one of the most fun Classical songs for Easter. Easter celebrations and traditions vary widely across the world. No matter how you celebrate Easter or the coming of Spring, there is plenty of fantastic music for that special occasion. What are some of your musical Easter favourites?