It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Showing posts with label Franz Liszt. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Franz Liszt. Show all posts

Thursday, September 15, 2022

Friday, August 12, 2022

Reading Franz Liszt: The Poetry Behind the Piano Music

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

“I find Roberts’ argument most persuasive”

In the introduction to his new book, pianist Paul Roberts recounts a conversation with “an elderly and much celebrated piano teacher” when he was just starting out as the inspiration for a lifetime’s fascination with literature and language and the essential connections between literature and music: “I introduced myself. I cannot remember quite how the topic came about, but within a few minutes we were talking about Liszt’s great triptych of piano pieces known as the Petrarch Sonnets, inspired by the love poetry of the 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca. “Oh!” I enthused, “those poems …!” She entered her studio. “We don’t need them,” she said, and closed the door. I was deflated. And dumbfounded.”

In the introduction to his new book, pianist Paul Roberts recounts a conversation with “an elderly and much celebrated piano teacher” when he was just starting out as the inspiration for a lifetime’s fascination with literature and language and the essential connections between literature and music: “I introduced myself. I cannot remember quite how the topic came about, but within a few minutes we were talking about Liszt’s great triptych of piano pieces known as the Petrarch Sonnets, inspired by the love poetry of the 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca. “Oh!” I enthused, “those poems …!” She entered her studio. “We don’t need them,” she said, and closed the door. I was deflated. And dumbfounded.”

Paul Roberts feels that music comes from sources beyond simply itself – from, for example, the composer’s life experience, the influence of others, and, in the case of Liszt, poetry and literature, and that as pianists we do the music, and its composer, a disservice by not paying attention to these external sources of inspiration. In his engaging, eloquent and highly readable text, Roberts explores what he believes to be an inseparable bond between poetry and the piano music of Franz Liszt, and how literary inquiry affects musical interpretation and performance. For Roberts, an appreciation of the poetry which inspired or informed Liszt’s music gives the pianist, and listener, significant insights into the composer’s creative imagination, bringing one closer to his music and allowing a deeper understanding, and, for the performer, a richer, more multi-dimensional interpretation of the music. It also offers a better appreciation of Liszt the man: too often dismissed as a superficial showman, in this book Roberts reveals Liszt as a man of passionate intellectual and emotional curiosity, who read widely and with immense discernment, all of which is reflected in his music. As Alfred Brendel said, “Liszt’s music….projects the man”.

Paul Roberts © Viktor Erik Emanuel

Poetry and literature were meat and drink to Franz Liszt, who performed in and attended the cultural salons of 1830s Paris where he knew writers such as Victor Hugo and George Sand. He was familiar with the writing of Byron, Sénancour, Goethe, Dante, Petrarch and others, and his scores are littered with literary quotations which offer fascinating glimpses into the breadth of his creative imagination and what that literature meant to him. For the pianist, they provide an opportunity to “live inside his mind” and open “our imaginations to the wonder of his music”.

Perhaps the most obvious connection between Liszt and poetry is his Tre Sonetti del Petrarca – the three Petrarch Sonnets. They began life as songs which Liszt later arranged for piano solo, and included them in the Italian volume of his Années de pèlerinage. Liszt and his lover Marie d’Agoult spent two years in Italy and it was here that Liszt was exposed to the marvels of Italian Renaissance art and architecture and the poetry of Dante and Petrarch.

The poetry of Petrarch was central to Liszt’s creative imagination and in his triptych inspired by the Italian poet’s sonnets, we find an extraordinary depth of expression and emotional breadth. In the chapter ‘The Music of Desire’, Roberts explores Petrarch’s sonnets in detail and demonstrates how Liszt translates the passion of the poet into some of the finest writing for piano by Liszt, or indeed anyone else.

Perhaps because I have studied and performed these pieces myself, a study which included close reference to Petrarch’s poetry, it is here that I find Roberts’ argument most persuasive, that the pianist really needs this literary context and understanding to bring the music fully to life. He shows how Liszt responds to the ebb and flow of emotions in Petrarch’s writing, in particular in the most passionately dramatic of the three sonnets, No. 104, “Pace no trovo” (I find no peace), where the poet veers almost schizophrenically between extremes of emotion, from the depths of despair to ecstasy.

Franz Liszt

Subsequent chapters explore other great piano works – the extraordinary B-minor Sonata which Roberts believes is firmly connected to that pinnacle of nineteenth century European literature, Goethe’s Faust, the existentialism of Vallée d’Obermann, a work which exemplifies the Romantic spirit, and its relationship with Etienne de Sénancour’s cult novel Obermann, the “aura” of Byron and his Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage which pervade the Swiss volume of the Années alongside Liszt’s personal experience of the majestic landscape of Switzerland and the Alps. The final chapter explores the Dante Sonata and Liszt’s reverence for The Divine Comedy at a time when Dante’s poetry was being rediscovered by English and European Romantic writers like Keats, Coleridge, Shelley and Stendhal. Throughout, Roberts conveys the power of literature to awaken and inspire the Romantic imagination and sensibilities, and demonstrates how this might inform the way one performs Liszt’s music – from the physical cadence of poetry to its drama, narrative arc and emotional impact which had such a profound effect on Liszt and which infuses his music in almost every note. Here Liszt finds a new kind of expression in which, in his own words, music becomes “a poetic language, one that, better than poetry itself perhaps, more readily expresses everything in us that transcends the commonplace, everything that eludes analysis”.

A useful Appendix explores the influence of other poets such as Alphonse de Lamartine and Lenau, with analysis of other pianos works, including Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude, the Mephisto Waltz, the two St Francis legends, and Mazeppa, inspired by a poem by Victor Hugo.

In this book, Paul Roberts reveals the essence of Liszt literary world, providing the pianist with valuable insight and inspiration with which to appreciate, shape and perform his music.

Reading Franz Liszt: Revealing the Poetry behind the Piano Music is published by Amadeus Press, an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield, USA.

Tuesday, September 28, 2021

Bringing out the National Song: Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies

by Maureen Buja , Interlude

Franz Liszt

In 1839, Franz Liszt (1811-1886) returned to Hungary, which he had left in 1822 at age 11. In the new nationalism that was sweeping Europe, he was hailed as a true Hungarian champion. As part of his musical explorations of his home country, he was fascinated by gypsy music and started to transcribe it for inspiration. Later researchers, such as Bartók and Kodály, found that Liszt’s gypsy music was regular art music played in a gypsy style, rather than their original music, but no matter, it served as an inspiration for Liszt.

Auguste Alexis Canzi: Franz Doppler (1853)

Liszt wrote a series of piano works between 1839 and 1847 and published them under the title Magyar dallok / Ungarische National-melodien (Hungarian Songs / Hungarian National Melodies). These included 15 Hungarian Rhapsodies; 4 more were written later. Six of the Hungarian Rhapsodies were orchestrated by Franz Doppler. Flautist, conductor and composer Doppler had met Liszt in Weimar in 1854 where Doppler and his brother had been performing. Later, Doppler was in Pest, Hungary, as principal flautist at the German Theatre and then, from 1841-58, as flautist and ballet conductor at the Hungarian National Theatre. Doppler’s role as orchestrator is unknown, but in Liszt’s will of 1860, he insisted that the orchestration for the Hungarian Rhapsodies had to be credited as ‘orchestrated by F. Doppler and revised by F. Liszt.’

Franz André

The Hungarian Rhapsody No. 3 in D major is an orchestration of the piano Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6 in D flat major. It was dedicated to Count Antal Apponyi. It is made up of 4 popular Hungarian songs, It opens with a march-like theme before moving to a quicker Presto. Next follows a Lassu, which originally had a text of surprising sadness: My father is dead, my mother is dead, and I have no brothers and sisters, and all the money that I have left will just buy a rope to hang myself with.’ This traditional text of despair is followed by a lively Friss to change the mood.

Monday, September 20, 2021

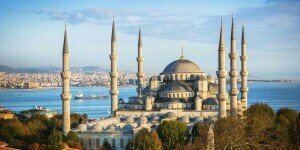

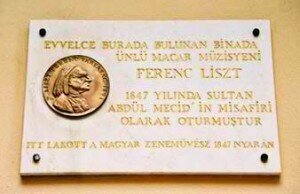

Franz Liszt in Istanbul

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Franz Liszt

Istanbul

Sultan Abdul-Medgid

Bosphorus

Çırağan Palace in 1840s © Wikiwand

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.

Liszt also gave a number of public concerts, including a musical matinee on 18 June at the Franchini Mansion at Buyukdere. Further private and public concerts were held at the Fethi Pasha Mansion and the Russian Embassy at Pera on 28 June. During this concert, “Liszt saw the panorama of Istanbul from the window and got really excited of seeing the east and the west at the same time. He even thought that he could seen Mount Olympus in the distance.” During his five-week stay, Giuseppe Donizetti hosted Liszt and he arranged accommodations for him at the home of the piano manufacturer Alexander Kommendinger. Donizetti had previously composed two marches for the Sultan, and at Liszt’s request, Donizetti gave him his compositions. “Liszt was in my house,” he writes. “He has just left. He wanted the notes of the two marches I composed for the Sultan. He said he was going to work them into variations sets.” Liszt first played the variations during concerts at Buyukdere on 14 and 15 June. Liszt eventually wrote out the manuscript and gave it to the Austrian ambassador, who passed it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who in turn presented it to the Sultan. In return, Liszt received the already mentioned enamel box studded with diamonds. Additionally, the Sultan handed Liszt a special seal, with the name of the composer written in Arabic alphabet with Turkish letters, and we do know that Liszt used it to seal a number of his letters. As it turns out, Istanbul delivered the perfect setting for Liszt to say goodbye to his life as a traveling virtuoso.(C) 2021 by Interlude

Thursday, July 23, 2020

A digital artist is creating remarkable 3D portraits of Brahms, Liszt and Chopin

By Maddy Shaw Roberts, ClassicFM

|  |

The great composers’ faces, reconstructed as if they are alive today.

An artist has been crafting digital portraits of the great Romantics, bringing four musical greats once shrouded in awe and mystery into the modern world.

Chopin, Liszt, Brahms and Schubert can all be admired in 3D and in color, as if reborn from the ashes.

Hadi Karimi, the Iranian CG artist behind the new renderings, is an expert in sculpting 3D portraits of Hollywood stars and other famous figures. But, he says, he’s “always been a fan of classical music”. So, he decided to take on a new project.

“We grew up with all these beautiful symphonies and memorable melodies, but do we know the minds behind them?” Karimi tells Classic FM.

“Sometimes we remember them by just a name and if we’re lucky there’s a painting or a black and white photo from centuries ago that could barely show us what they actually looked like.”

— Hadi Karimi (@HadiKarimi_Art) July 13, 2020

Faces, as Karimi says, get lost in history. Photographs quickly deteriorate, and we are left with only death masks and portraits to rely on for an accurate picture of what our treasured historical figures actually looked like.

Karimi adds: “The mid-19th century was the time that photography started to become popular throughout Europe and paintings, life masks, began to fade. Daguerreotypes were very expensive and only the wealthy could afford them – and the same with masks and paintings!”

Of Chopin, there are just two known photographs: an unflattering daguerreotype, which was taken when the Polish composer was rather ill; and a reproduced version of a deteriorated photograph, that was lost during the Second World War. With no ‘true’ photographs to play with, Karimi worked from the composer’s death mask.

Frédéric Chopin #CG #Likeness— Hadi Karimi (@HadiKarimi_Art) June 1, 2020

Sculpted in @pixologic #ZBrush

the color map was painted in @Substance3D #Painter

Rendered in @AdskMaya with @arnoldrenderer

used #Xgen core for the hair.https://t.co/hrVZ2llqMh pic.twitter.com/85RJ4FqeTX

For Schubert, who – incredibly – wasn’t famous during his lifetime, the situation was equally tricky, as the Austrian early Romantic couldn’t have afforded a skilled artist to do his portrait.

“Most of the portraits of him were done decades after his death when his music finally started to make it to the mainstream,” Karimi explains. “All I could find as a reference was just one photo of a cast impression of his life/death mask, unfortunately the original mask is lost or destroyed in the market.”

Franz Schubert #CG #Likeness— Hadi Karimi (@HadiKarimi_Art) June 12, 2020

Sculpted in @pixologic #ZBrush

the color map was painted in @Substance3D #Painter

Rendered in @AdskMaya with @arnoldrenderer

used #Xgen core for the hair.https://t.co/hrVZ2llqMh pic.twitter.com/82rgwbr84r

Liszt is based on photographs of the composer, taken by Franz Hanfstaengl in 1858. And for the former, “Luckily there are many photographs of Brahms on the internet, even from his teenage years! I tried to picture him in his thirties (around 1860).”

All the sculpting was done using ZBrush, a digital sculpting tool that combines 3D and 2.5D modelling, texturing and painting. The colour texture was painted in Substance Painter, and for the German maestro’s floppy locks, the artist used XGen, an interactive tool used for creating realistic-looking hair.

“Thanks to the current technology along with the techniques that I’ve learned throughout my career as a CG artist, I can present to you the result of days and nights of my works and studies,” Karimi says.

“In this series of facial reconstructions, not only did I gather the references like photographs, paintings, life/death masks, … but also took a step further to study their personality so that I could reflect that in their facial expressions.

Liszt Ferenc 🇭🇺https://t.co/m6OOeL8nQJ pic.twitter.com/5QEl7AhdpN— Hadi Karimi (@HadiKarimi_Art) July 10, 2020

“I hope that I did them justice,” Karimi adds.

The reaction to his portraits has been extraordinary. “Amazing as usual,” one Twitter user comments. Other have requested Beethoven and Wagner as the next composers to get the 3D treatment.

British pianist and Chopin expert Warren Mailley-Smith, who five years ago memorised the Romantic’s entire repertoire for solo piano, remarked it was “quite incredible to actually see the man”.

“Some of these great composers can end up with such legendary, god-like status it’s easy to forget how perfectly ordinary as human beings they otherwise were.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)