We don’t really think about what the heart symbol (♥) really means. We know it’s not the shape of a real heart, which is much more asymmetrical. It’s been discovered in jewelry dating back to 3,000 years BCE, and is very much like shape of a seed of a plant used as a contraceptive. It was in the Middle Ages, however, that the equation between the heart symbol and love was made. Starting in the 15th century and continuing today, hearts mean love.

When we see books in the shapes of hearts, then, what are we to think of them? In this anonymous late 15th century painting of St. Jerome and St. Catherine, she’s reading a book. The two saints are surrounded by their attributes: St. Jerome and his lion and St. Catherine and the shattered wheel (known as a Catherine Wheel) representing the unsuccessful torture of Catherine by Emperor Maxentius. In her hands, she holds a heart-shaped book.

Anonymous: St Jerome and St Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1480 – c. 1490) (Rijksmuseum)

Another image from the same time shows a young man holding a heart-shaped book. Here, it’s thought that the heart shape might be related to St. Augustine, whose attribute was a flaming heart.

Master of the View of Sainte Gudule: Young Man Holding a Book (ca. 1480)

(Metropolitan Museum of Art)

When heart-shaped books are closed and held between the hands, they form, in the liturgical sense, the shape of praying hands.

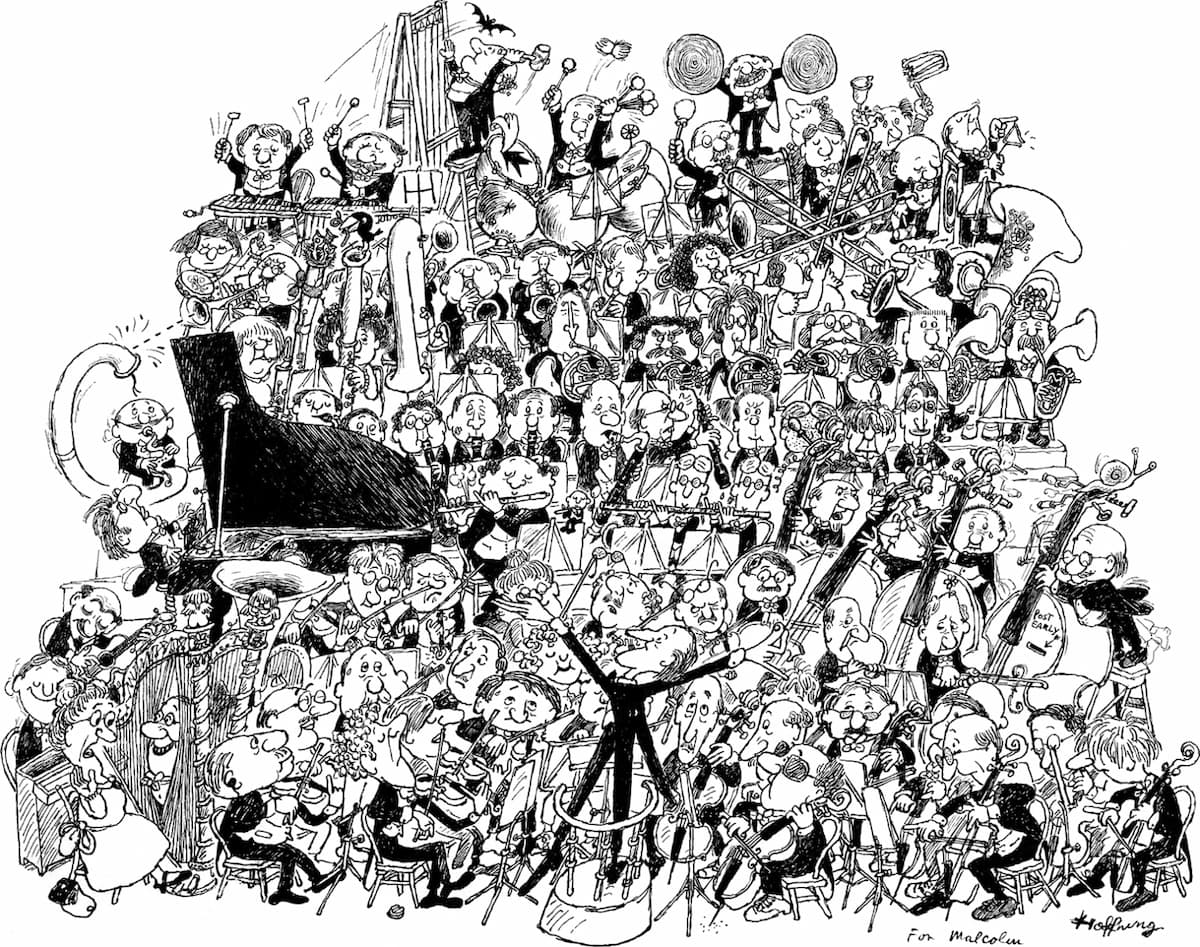

The Chantilly Codex, held in the museum at the Château de Chantilly, France, has an unusual musical work that was added to the beginning of the book. The book dates from ca. 1350-1400 and contains 112 musical works, mostly by French composers. The added work was written by the composer Baude Cordier (ca. 1380-ca. 1440) and is written in the shape of a heart – the top curved lines are the top voice and underneath are the Tenor and Contratenor lines. Below, filling out the point of the heart, are additional lyrics. The text, ‘Belle, bonne, sage, plaisant..’. means ‘Beautiful, good, wise, and pleasing…’ and after giving her his songs, the first verse closes with : ‘…my heart I also give to you.’ It’s a song for the new year and he urges his lover to take them as her due.

Belle, bonne, sage, plaisant (Chantilly Codes)

The heart-shaped music is a play on the name of the composer, where ‘cor’ of ‘Cordier’ means ‘heart,’ in addition to being his gift to her.

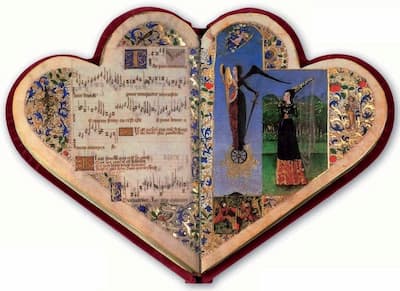

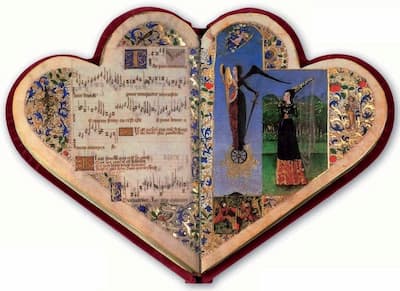

An entire music book in the shape not of a single heart, but a double heart was created in the Chansonnier Cordiforme (Heart-shaped Songbook). This sumptuously decorated double-heart book was commissioned between 1470 and 1475 by Jean de Montchenu, the Bishop of Agen (1477) and then Vivier (1478-1497). The book is bound in red velvet. The 44 pieces of music come from both Italian and French sources. The music is bordered with elaborate gold-touched illustrations of animals, including cats, dogs, and birds, and flowers and plants. In this page of music, there’s a fantastic beast on the left, a monkey with a book at the bottom of the page, and an elongated bird at the top and on the right side.

Detail of Chansonnier Cordiforme, with Bedyngham’s O rosa bella

(Bibliothèque nationale de France)

As a double-heart book, the design is intended to represent two lovers who are sending message to each other in the songs. The songs seem to reflect both his and her points of view: he goes out one morning and encounters a shepherdess, when he asks if she could love him, she replies that she loves another who entertains her with his pretty flageolet (L’autre jour). In another song, she says she is a pure girl and complains that jealousy is bearing false witness against her but says that virtue will be her defense (Be lo sa Dio). He compares his lover to a goddess because she is so full of goodness that everyone should pay her homage (De tous biens plaine). Each side can speak its part and say, often in coded words, how they regard the other.

There are two striking illustrations in the book: in this image from the beginning of the book, Cupid in the sky shoots arrows at a young girl and to the left, Fortune stands on her ever-turning wheel.

Chansonnier Cordiforme, fol. 3v, with J’ay pris amours (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

On another page, 2 lovers walk in a room. In the margins, a cupid has his arrow at the ready and floral and fauna fill the other corners of the heart. Those are the only two full-page images in the book – the other pages are filled with music.

Chansonnier Cordiforme, fol. 23v, with Gentil Madonna (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The music in the book is given without composer’s names, but in the centuries since the book was created, the composers have gradually been identified and include the big names of the 15th century: Guillaume Dufay, Gilles Binchois, Johannes Ockeghem, Antoine Busnois and other smaller names: Hayne van Ghizeghem, Vincenet du Bruecquet, the theorist Johannes Tinctoris, and English composers such as Robert Morton and Johannes Bedyngham.

There are other heart-shaped books, but they’re very rare. One example is the 16th-century Danish Hjertebog (Heart book), that contains 83 love ballads in Danish.