However, not all of the composers who contributed to American classical music have been men! On the contrary, many of the best composers in American history have been women.

Today we’re looking at the lives and work of eight American women composers.

Amy Beach (1867-1944)

Amy Beach is widely considered to be the first major American woman composer.

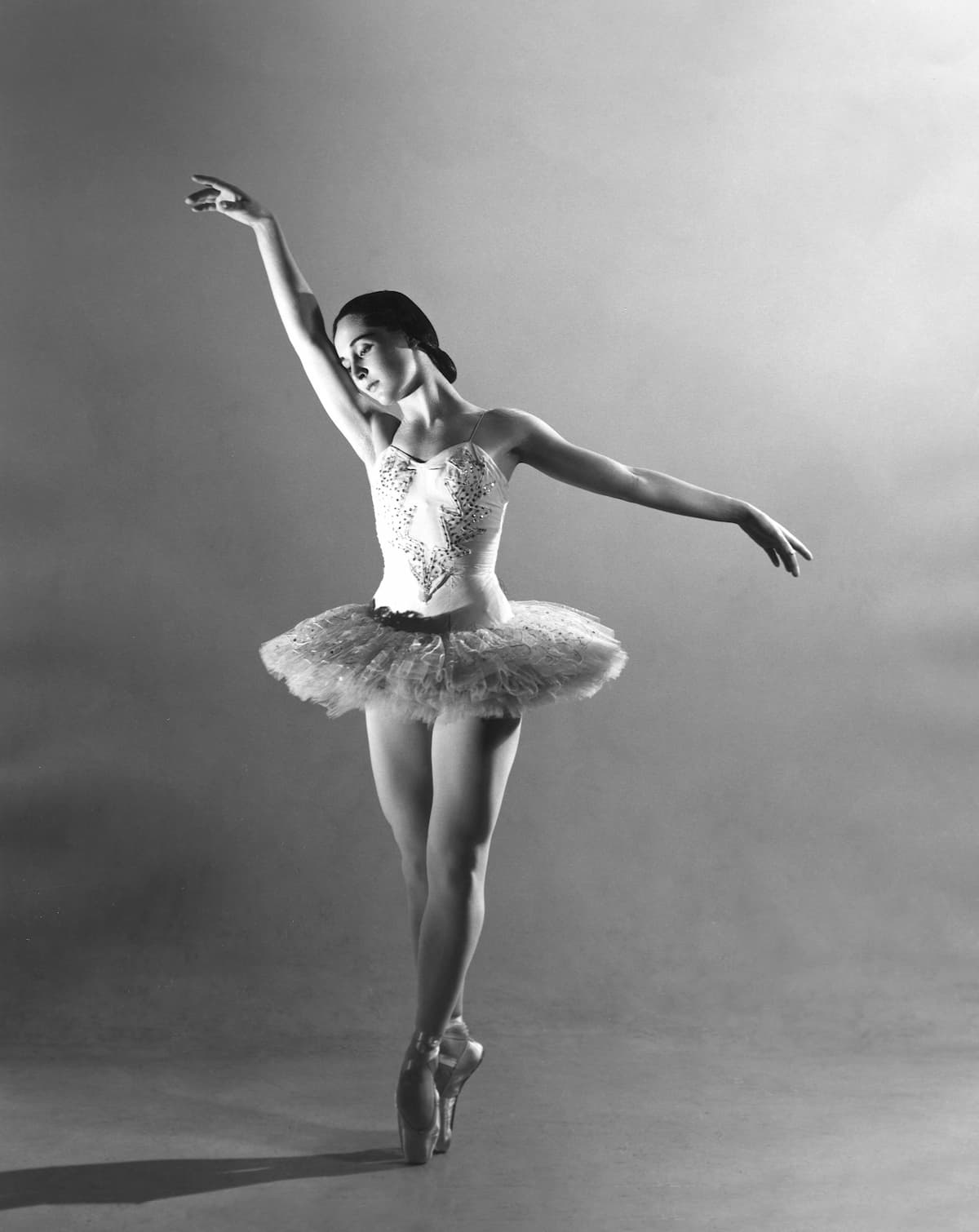

Amy Beach

She was born Amy Cheney in 1867 in New Hampshire. From the beginning, it was clear she was a prodigy. At the age of just four, she composed waltzes in her head while out of the house, then returned home to play them on piano.

She began formal piano lessons with her mother at the age of six. A couple of years later, her family moved to suburban Boston. At fourteen, she briefly studied harmony and counterpoint. This would be her only formal compositional training.

She made a brilliant orchestral debut at 16. But two years later, in 1885, her performing career came to a halt when she married a doctor named H. H. A. Beach, who was twenty-four years her senior.

A condition of the marriage was that she could only perform in public twice a year, and she had to donate any money she earned to charity. Because of this, she began gravitating toward composition.

In 1892, she had her Mass in E-flat Major premiered at the Handel and Haydn Society.

Four years later, the Boston Symphony premiered her Gaelic Symphony, marking the first time a major American orchestra had played a symphony by a woman.

Four years after that, the Boston Symphony premiered her piano concerto.

In 1910, she was widowed, a change in circumstance that granted her freedom to pursue a performing career.

Margaret Ruthven Lang (1867-1972)

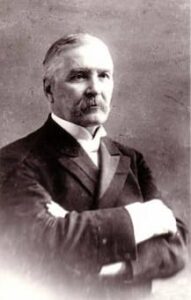

Margaret Ruthven Lang was born in Boston to musical parents. Her father was a conductor, pianist, and composer and ensured that she had a good musical education.

In 1886, she went to Munich to study violin. After she returned to America, she studied composition with professors from the New England Conservatory of Music.

Margaret Ruthven Lang

In 1893, the Boston Symphony premiered her Dramatic Overture, marking the first time a major American orchestra had played a woman’s work. (It just barely beat out Beach’s Gaelic Symphony.)

Sadly, Lang had fierce self-doubts and destroyed many of her manuscripts. It seems likely that her orchestral works were among these.

After her father’s death in 1909, she became less involved with music and more interested in religion, becoming a devoted Episcopalian. Her final work, Three Pianoforte Pieces for Young Players, was published in 1919.

However, she lived for decades more and ended up setting a patron record at the Boston Symphony, having been a subscriber there for 91 consecutive years. She died just short of her 105th birthday.

Florence Price (1887-1953)

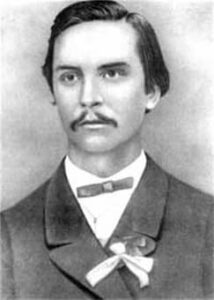

Florence Price was born to a Black family in Little Rock, Arkansas. Her father was a dentist and her mother was a music teacher.

From an early age her musical talent was apparent. She gave her first public piano performance at the age of four, and she had her first piece published when she was eleven.

Florence Price © University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections

She graduated from high school at the age of fourteen and then enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music.

After graduation in 1910, she returned to Little Rock to teach and start a family. She married a lawyer named Thomas J. Price in 1912 and had three children with him.

To escape the ever-present domestic terrorism of the Jim Crow era, the family moved to Chicago in 1927. Surrounded by the artists that made up the Chicago Black Renaissance, Price returned to her musical career.

She also made a big life change when she divorced in 1931. She remarried the same year to an insurance agent named Pusey Dell Arnett, but the relationship fizzled out. During this time of transition, to make ends meet, she played organ at movie theaters and roomed with friends.

In 1932, her hard work paid off when she won the Wanamaker Foundation Award for her Symphony in E-minor. The following year, the Chicago Symphony performed the symphony, making it the first time a Black woman had seen her work played by a major American orchestra.

Florence Price died in 1953 of a stroke. She has been experiencing a revival over the past few years in America as audiences are rediscovering her charming, deeply moving work.

Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901-1953)

Ruth Crawford Seeger

Ruth Crawford Seeger was born in Ohio in 1901. Her minister father died young and her mother was forced to open a boarding house to make up for the loss of his income.

In 1907 she began piano lessons, and after high school, she settled on a musical career.

In 1921 she moved to Chicago and began attending the American Conservatory of Music. She earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees there between 1921 and 1929.

After her graduation, she became the first woman composer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship. She used the money to study in Paris and Berlin.

In 1932 she married her composition teacher, Charles Seeger, who was fifteen years her senior. From 1933 to 1943 she had four children with him.

Her most famous works date from between 1930 and 1933, when she was writing fearlessly modernist works that embrace dissonance and serial techniques.

She died of intestinal cancer in 1953.

Margaret Bonds (1913-1972)

Margaret Bonds was born Margaret Majors in Chicago. Her parents were a Black doctor and his church musician wife, who divorced when she was four. She took her mother’s maiden name and became known as Margaret Bonds.

Margaret was a prodigiously gifted child who wrote her first piece of music at the age of five. In high school, she studied composition with Florence Price and William Dawson.

Margaret Bonds

In 1929, when she was sixteen, she began studying at Northwestern University, where she earned her master’s degrees in piano and composition. The atmosphere at the school was deeply racist and difficult for her to endure.

While at Northwestern, in 1933, she soloed with the Chicago Symphony, becoming the first Black person to ever do so.

In 1939, with her degrees from Northwestern in hand, she moved to New York City to go to Juilliard. She married a probation officer in New York in 1940.

Bonds was good friends with poet Langston Hughes and they collaborated on a variety of creative projects over the years.

She also spent time creating projects that would uplift Black artists and the wider community.

In 1964 she composed one of her most ambitious works, the Montgomery Variations, which graphically portrayed the violence and resilience of the 1960s civil rights movement. She dedicated the work to Martin Luther King, Jr.

In 1966, she moved to Los Angeles, where she died in 1972.

Julia Perry (1924-1979)

Julia Perry was raised in Kentucky and Ohio.

She studied voice, piano, and composition at Westminster Choir College. She continued her postgraduate studies at the Berkshire Music Center and Juilliard.

Julia Perry

In 1952 she traveled to Paris to study with legendary teacher Nadia Boulanger. She spent a little over five years in Europe, then returned to America, where she became a teacher herself.

She preferred to write for voice, and wrote several incredible works in vocal genres, including her Stabat Mater. But she also wrote great works for instrumental ensembles, too, including twelve symphonies, two piano concertos, and a violin concerto.

At the time of her death she was working on an opera, which remains unfinished.

Jennifer Higdon (1962-)

Jennifer Higdon was born in Brooklyn, New York, to a painter and his wife, and raised in Georgia and Tennessee.

She didn’t listen to much classical music as a child, and only began playing an instrument in high school, when she started learning percussion and flute.

Jennifer Higdon

She attended Bowling Green State University for flute performance and began studying composition there. She later earned her master’s degree and PhD in composition from the University of Pennsylvania, where she studied under George Crumb.

In 1994 she became a professor at the Curtis Institute of Music, the most selective music school in America.

Her compositional style is tonal and accessible; it’s sometimes called neoromantic. Her music has received popular and critical acclaim. She has won three Grammy Awards for Best Contemporary Classical Composition (they were awarded for her percussion concerto, viola concerto, and harp concerto). In 2010 she won the Pulitzer Prize for Music.

Jessie Montgomery (1981-)

Jessie Montgomery was born to a composer and a playwright in New York City in 1982. She earned her bachelor’s degree in violin performance from Juilliard, and her master’s degree in film and media composition from New York University.

She values diversity, arts education, accessibility, and uses her music to engage with ideas and issues surrounding equity and social justice.

Jessie Montgomery

Her work blends all kinds of musical influences from all around the world, including countries like Mexico, Cuba, and Zimbabwe, and genres like swing, samba, and even techo.

In 2021, she was named the Chicago Symphony Composer-In-Residence.

Today she is one of the most frequently performed new music composers in America.