It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Sunday, November 13, 2022

Thursday, June 9, 2022

‘Maestro’: First look at Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein in Netflix biopic

By Sophia Alexandra Hall

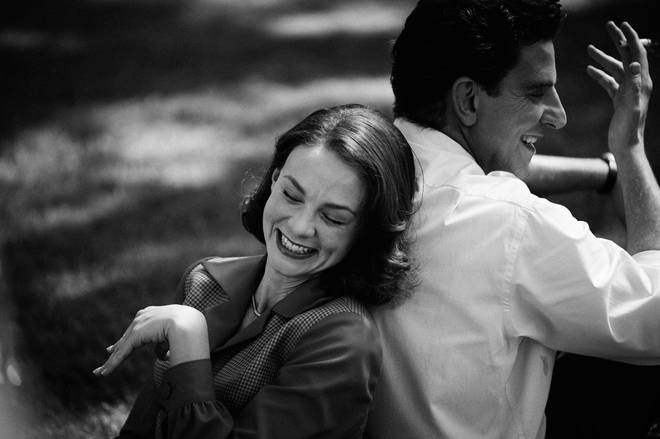

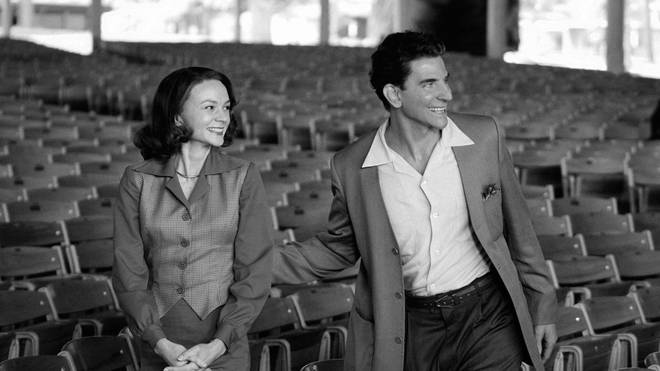

@sophiassocialsBradley Cooper and British actress, Carey Mulligan, star in the new Netflix biopic about the legendary American conductor and composer, Leonard Bernstein.

Directed by and starring Bradley Cooper as the maestro himself, the film is set to hit Netflix in 2023. Alongside Cooper is Carey Mulligan who plays the conductor’s wife, stage and TV actor Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein.

Fans of the streaming service have had an exclusive first look at Cooper and Mulligan in their biopic roles with images released on Netflix’s social media pages yesterday afternoon.

Here are the first stills of Cooper and Mulligan from the upcoming Netflix production portraying the ‘American classical music wonder boy’ and his star actress wife....

Born on 28 August 1918, Leonard Bernstein married Chilean-American TV and stage actor, Felicia Cohn Montealegre, in 1951.

Though a somewhat unsettled marriage due to Bernstein’s well-documented homosexuality, there was a strong love between the two artists, making their connection much more than a relationship of convenience, despite their individual sexual preferences.

The couple had three children together; Jamie, Alexander and Nina.

In an interview with Classic FM, Jamie Bernstein was quick to correct the description of the new netflix film saying, “It’s not a biopic, strictly speaking, it doesn’t tell the story of Leonard Bernstein from birth to death – it’s not that kind of a film at all.

“In fact, it’s a portrait of our parents’ marriage. It’s about something very specific and very personal for [my siblings and I].

“We’re really struck by the fact that this was the aspect of the story that Bradley decided to focus in on and we’re very excited about Carey Mulligan as our mother Felicia; I promise you she is going to send it to the moon in a rocket.”

Montealegre was aware of Bernstein’s sexuality, and in a letter shortly after their marriage in 1951 she wrote, “If I seemed sad as you drove away today it was not because I felt in any way deserted but because I was left alone to face myself and this whole bloody mess which is our ‘connubial’ life.

“I’ve done a lot of thinking and have decided that it’s not such a mess after all. First: we are not committed to a life sentence – nothing is really irrevocable, not even marriage (though I used to think so). Second: you are a homosexual and may never change – you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depends on a certain sexual pattern what can you do? Third: I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr or sacrificing myself on the L.B. altar. (I happen to love you very much—this may be a disease and if it is what better cure?) Let’s try and see what happens if you are free to do as you like, but without guilt and confession, please!

“The feelings you have for me will be clearer and easier to express—our marriage is not based on passion but on tenderness and mutual respect.”

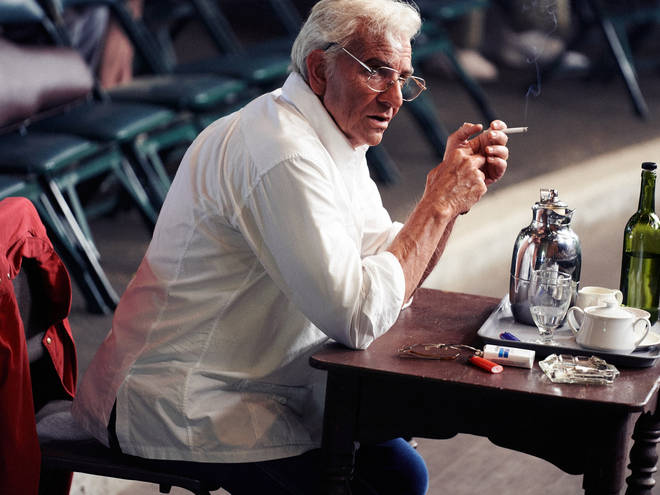

The film follows Bernstein across multiple decades, and fans are already excited to see Cooper’s visual similarity in the photographs of the actor’s portrayal of the conductor at an older age.

“If this is Bradley Cooper, the makeup artist should get an Oscar,” one Facebook commenter noted.

Another said, “It’s more than the makeup, it’s the posture, the gesture, the way he holds his cigarette.”

We’re just as excited as the Facebook comments section to see what Cooper will bring to this role of the beloved American artist.

With a due date yet to be announced, but the film expected next year, we’re sure that something’s coming... something good.

Friday, May 27, 2022

The Greatest Composers of Film Music

Satie, Ibert, Tailleferre, Milhaud and Honegger

Tomb Raider

I was still too young to actually see the first “Tomb Raider” film release in 2001. But when I first watched it some years later, I thought it was the biggest thing since the invention of the handbag. Finally, there was an empowered women beating up all those macho male characters. Later I played all the video games, and “Lara Croft” became a cultural phenomenon that is still going strong 25 years later. Basically, they are pretty silly movies but you can’t beat swashbuckling action films if you want to enjoy a couple hours of mindless fun. The Hollywood studios have given us countless action/adventure movies, and that formula has been a huge commercial success. No wonder that they called the 1930’s Hollywood’s Golden Age. In Europe meanwhile, audiences had little taste for blowing up the world movies after World War I, so filmmakers tended to focus more on the artistic qualities of film. While American composers of film music “seemingly held that new medium in distain,” they imported the Viennese composers Max Steiner and Wolfgang Eric Korngold. In Europe meanwhile, a significant number of art music composers embraced this new challenge. In France, in particular, a number of big-name composers eagerly adopted the new art form, including Erik Satie, Jacques Ibert, Germaine Tailleferre, Darius Milhaud, and Arthur Honegger.

Erik Satie & Francis Picabia, Jean Biorlin (prologue de Relache)

When eccentricity and classical music are used in the same sentence, Erik Satie (1866-1925) immediately comes to mind. Irreverent, disrespectful, contemptuous of tradition, forcefully direct and brutally honest, Satie famously wrote underneath his self-portrait, “I have come into the world very young, into an era very old.” In 1924, Satie collaborated on a ballet production with Francis Picabia, and since both artists had a taste for controversy, audiences immediately knew what to except. It was called Relâche, loosely translated into “No Performance today,” or “Theatre Closed,” and it had really no plot. A female character dances with a changing number of male characters, including a paraplegic in a wheelchair. And there is a man dressed as a fireman who wanders around the stage, pouring water from one bucket into another.

Relâche Part 1

Between acts and after the overture, the film “Entr’acte” was shown. An experimental film by critic Rene Clair, it featured scenes filmed in Paris that included a dancing ballerina with moustache and beard, a hunter shooting a large egg, and a mock funeral procession with a camel-drawn hearse. Satie composed the music for both the ballet and the film, and his score for “Entr’acte” was called revolutionary. “It is an excellent example of early film music, as different segments reflect and support the rhythm of the action and serve as a kind of neutral rhythmic counterpoint to the visual action.” Satie used a number of popular tunes, and while the ballet is little more than nonsensical fragmented spectacle to make Dada proud, “the music is essentially unified and symmetrical.” The premiere, as you might expect, did not go well and audiences and critic attacked “the stupidity of the staging and the inanity of the musical score.” Today we recognize it “as an inventive score without peer, at once durable and distinguished, with “Satie having understood correctly the limitations and possibilities of a photographic narrative as subject matter for music.”

Jacques Ibert: 4 Chansons de Don Quichotte

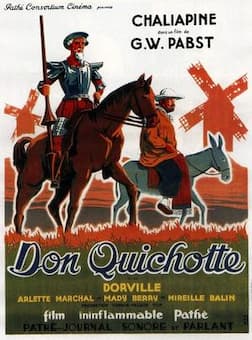

Don Quichotte

I have always loved the music of Jacques Ibert (1890-1962) because he doesn’t take himself or classical music all too seriously. He once said that he only agreed to write music that he was happy to listen to himself. “I want to be free,” he writes, “independent of the prejudices which arbitrarily divide the defenders of a certain tradition, and the partisans of a certain avant garde.” His biographer writes, “Ibert’s music can be festive and gay…lyrical and inspired, or descriptive and evocative…often tinged with gentle humour.” That’s a perfect recipe for writing incidental music for the theater and music for film. In fact, Ibert was a prolific composer when he came to cinema scores, writing music for more than a dozen French films, and two pictures for American directors Orson Welles and Gene Kelly. In 1933, Georg Wilhelm Pabst, one of the most influential German-language filmmakers during the Weimar Republic, directed Don Quixote, the film adaptation of the classic Miguel de Cervantes novel. It was made in three versions—French, English, and German—and featured the famous operatic bass Feodor Chaliapin. The producers separately commissioned five composers—Ibert, Ravel, Delannoy, de Falla, and Milhaud to write the songs for Chaliapin, each composer believing only he had been approached. Jacques Ibert’s music was selected for the film, and Ravel considered a lawsuit against the producers.

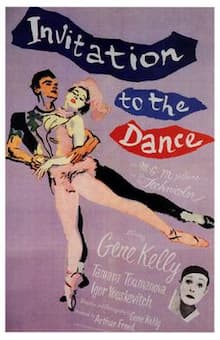

Invitation to the Dance

The American actor, dancer, and singer Eugene Kelly became incredibly famous for his performances in “An American in Paris,” and for “Singin’ in the Rain.” Kelly also starred in “Invitation to the Dance,” the first film he directed on his own. The film is a dance anthology that has no spoken dialogue, with the characters performing their roles entirely through dance and mime. The film consists of three distinct stories, written by Kelly, with the first segment “Circus” set to original music by Jacques Ibert. The plot is a tragic love triangle set in a mythical land sometime in the past. Kelly plays a clown, who is in love with another circus performer, played by Claire Sombert. She, however, is in love with an Aerialist, played by Youskevitch. The Clown, after entertaining the crowds with the other clowns, sees his love and the Aerialist kiss and wanders into a crowd in shock. That night he watches them dance together, and after the Lady finds him with her shawl, he confesses his love to her. The Aerialist finds them and thinks she has been unfaithful and leaves her. Determined to win her, the Clown tries to walk the Aerialist’s tightrope himself, only to fall to his death. Dying, he urges the two lovers to forgive each other. By the way, the movie was a colossal failure at the box office, but it is today regarded “as a landmark all-dance film.”

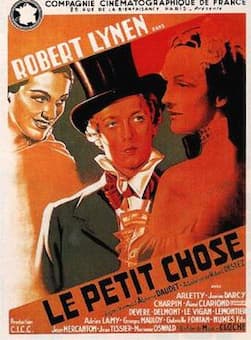

Le petit chose

Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983) was the only female member of the French group of composers known as “Les Six.” She was well-known for her intimate chamber music compositions, but it is generally less well-known that she scored music for thirty-eight films! And that includes music for a series of documentaries, and a number of wonderful collaborations with film director and producer Maurice Cloche. His career spanned for over a half-century, and he produced spy thrillers and films with religious and social themes. He is probably best known for “La Cage aux Oiseaux” (‘The Bird Cage); “Le Docteur Laennec,” the story of the inventor of the stethoscope; “Ne de Pere Inconnu” (Father Unknown) and “La Cage aux Filles” (The Girl Cage). Cloche founded a film society for young talents in 1940, which later became the Institute of Advanced Film Studies and France’s leading film school. Cloche was part of a group of directors that focused on poetic realism, but he did not neglect social subjects. His most famous documentaries on art included “Terre d’amour,” “Symphonie graphique,” “Alsace,” and “Franche-Comte.” In 1938 Cloche turned the autobiographical memoir by Alphonse Daudet into the film Le Petit Chose (Little Good-for-Nothing) starring Arletty, Marianne Oswald, and Marcelle Barry. The title is taken from the author’s nickname, and “Little Good-for-Nothing” is forced to accept a job as a Latin teacher in a college. He is expelled for having naively trusted one of his colleagues, and he departs to join his brother in Paris where he is dreaming of great literary career. As an interesting side-note, the movie features 14-year-old classical guitarist Ida Presti in a supporting role as a guitar player. Tailleferre composed a wonderfully flowing film store that is at once “bold and original, dissonant and exploratory, vigorous and soothing.” In her day, Tailleferre was greatly admired for her film work, which was “likened to the wispy work of the popular watercolorist Marie Laurencin.”

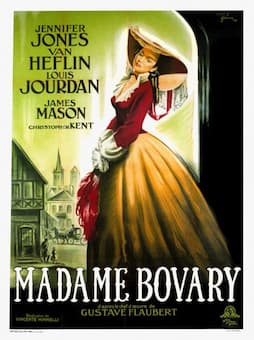

Darius Milhaud: L’album de Madame Bovary

Madame Bovary

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) composed over 400 compositions during his life, and given his love of the cinema, he also wrote music for 25 films. It all started with his first major success, the 1919 Surrealist ballet “Le Boeuf sur le toit,” (The Ox on the Roof). That work was originally subtitled a “Cinéma-symphonie,” and it featured fifteen minutes of music “rapid and gay, as a background to any Charlie Chaplin silent movie.” Milhaud was already composing music in the silent era, “with the now lost score to accompany Marcel L’Herbier’s avant-garde melodrama “L’Inhumaine.” The music is said to have matched the “film’s abrupt, expressionist rhythm, climaxing—for a scene where the hero resurrects his dead love in a futuristic laboratory—in a bravura cadenza scored solely for percussion instruments.” Always eager to experiment, Milhaud brought the opera into the cinema, as he used a backdrop movie screen to disclose the thoughts of his characters in his opera Christophe Colombe. In Dreams That Money Can Buy of 1947, Milhaud collaborated with the Surrealist/Dada super stars Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Alexander Calder, and Fernand Léger, and he received a visit from Renoir while he was composing the score for Madame Bovary.

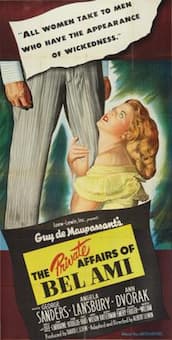

The Private Affairs of Bel Ami

Milhaud’s love for experimentation needed an eclectic use of music. He did admire Debussy and Mussorgsky but truly hated Wagner. Milhaud “happily threw in elements of whatever took his fancy—jazz, Brazilian dance rhythms, the medieval troubadour songs of his native Provence. Rather than cast his music in a predetermined style, he preferred to adopt whatever forms and materials seemed appropriate to the given task. This adaptability, together with his fluency of inspiration should have made him an ideal film composer. But his relationship with the movie industry remained oddly uneasy.” Milhaud spent much of his later life in America, but hated working for Hollywood. “He disliking the system of handing over the composer’s short score to professional orchestrators who churn out on a commercial scale musical pathos à la Wagner or Tchaikovsky.” He did, however, accept one Hollywood assignment titled The Private Affairs of Bel-Ami directed by Albert Lewin. Milhaud called him a “highly cultured man, and what is even rarer in those circles, genuinely modest.” Milhaud did orchestrate his own music, conducted the recording session and was present during the mixing. “The result was a score that vividly evoked the Paris of the Belle Epoque, but without the usual wash of romantic nostalgia.”

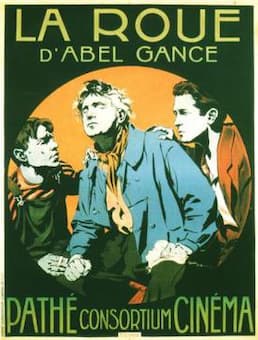

La Roue

Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) was critically acclaimed for both his concert music and his film scores during the interwar years in France. In terms of film scoring, Honegger is best remembered for his collaboration with Abel Gance, a pioneer film director, producer, writer and actor. Gance pioneered the theory and practice of montage, and he is best known for three major silent films J’accuse (1919), La Roue (1923), and Napoléon (1927). And Honegger wrote the music for all three silent films. J’accuse juxtaposes a romantic drama with the background of the horrors of World War I, and it is sometimes described as a pacifist or anti-war film. Work on the film began in 1918, and some scenes were filmed on real battlefields; can you imagine? The film’s powerful depiction of wartime suffering, and particularly its climactic sequence of the “return of the dead” made it an international success, and confirmed Gance as one of the most important directors in Europe. The only surviving score for the 1922 melodrama La Roue is an overture scored for medium-sized orchestra. There has been much speculation as to the rest of the music, and it is said “that Honegger put together a score consisting of pieces of his own and music from the classical repertoire.”

Arthur Honegger: Napoleon Suite

Albert Dieudonne as Napoleon_1927

Abel Gance’s silent masterpiece Napoleon of 1927 “exceeds the parameters of virtually every aspect of film culture. In the 1920s, its temporal gigantism horrified producers and its aesthetic invention flustered critics.” The film is recognised as a “masterwork of fluid camera motion, produced in a time when most camera shots were static. Many innovative techniques were used to make the film, including fast cutting, extensive close-ups, a wide variety of hand-held camera shots, location shooting, point of view shots, multiple-camera setups, multiple exposure, superimposition, underwater camera, kaleidoscopic images, film tinting, split screen and mosaic shots, multi-screen projection, and other visual effects.” It tells the story of Napoleon’s early years, and Gance had planned it to be the first of six films about Napoleon’s career, basically a chronology of great triumph and defeat ending in Napoleon’s death in exile on the island of Saint Helena.

Abel Gance and Arthur Honegger, 1926

Gance had struggled to make the first film, and given the enormous costs involved, he understood that the full project was impossible. Honegger believed that “cinematic montage differs from musical composition in that, while the latter depends on continuity and logical development, the film relies on contrasts. Music and sound must, therefore, adapt themselves to strengthening and complementing the visual element, while the whole must be an artistic unity.” Until now, the original cue sheet for Honegger’s music to Napoleon has not been found, so we don’t know exactly what music was played when. However, a number of musical autographs and orchestrated manuscripts have survived, and have been compiled into a wonderful Napoleon Suite sequence. There are so many more beautiful French movies and corresponding gorgeous music to explore, but in the next blog we will turn our attention to the two Russian giants Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev.

Friday, May 20, 2022

How Do Musicians Express Their Emotions through Music?

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

Music is a powerful means of communication, by which people share emotions, intentions, and meanings, and our personal engagement with music, whether in a live concert, listening to a CD or via a streaming service, is driven by the medium’s ability to convey and communicate emotion. Music can arouse strong feelings, recall memories; it can promote extreme happiness or engender feelings of deep love or loss…

Like speech, music has an acoustic code for expressing emotion, and even if a piece of music is unfamiliar, we can “decode” its message. Because of this, while musicians perform music according to their own interpretations, we can still understand the basic acoustic code: a crescendo indicates increased intensity or drama; a minor key suggests seriousness or melancholy; pauses create suspense and anticipation.

For the performer, the ability to communicate emotion, or tell a story, in music requires more than the technical facility to process what’s on the score. A good understanding of the structure of the music is important for a convincing, and communicative, musical performance, allowing the musician to respond to aspects such as variations in tempo and dynamics, harmonic and melodic tension and release, phrasing, repetitions, etc. By responding to these elements, the listener is given a set of musical “signposts” which guide them through the music, and bring cohesion, interest and variety to the performance.

A performer must resolve the entire depth of the ideas contained there. How often carefully notated shadings, accents, tempo changes reveal not simply a positive characteristic of sound but rather the untold sides of the author’s concept. How many directions we find in Schumann, Chopin, Scriabin, even Beethoven that a pianist should follow not in a real sound but by addressing the subtlest hints to the imagination of a listener!

– Samuil Feinberg

Communicating emotion is the most elusive aspect of the performer’s skillset, and is the fundamental reason why people – performers and listeners – engage with music. At a basic level, music communicates specific emotions through simple musical devices, for example:

- Happy – fast tempo, running notes, staccato, bright sound, major key

- Sad – very slow tempo, minor key, legato, descending sequences or falling intervals, diminuendo, ritardando

But there is something else which makes a performance particularly rich in expression or communication. Performance is generally regarded as a synthesis of both technical and expressive skills. Technical skills can be taught, while expression is more instinctive: it is of course possible to act upon expression markings in the score, but in order for these to sound convincing and, more importantly, natural, the performer must draw upon other factors, including extra-musical ones.

Many performers create a vivid internal musical and artistic vision of the music they are playing. This may include an aural model; the use of metaphors or adjectives to create a narrative or picture for the music; and personal experience, including extra-musical experiences. A performer’s own emotional experiences may influence the way they convey emotion in the music. This suggests that only a performer who has actually experienced the highs and lows of romantic love can perform, for example, Schumann’s Fantasie in C with the requisite emotional insight. Of course, not every performer will have the life experience, but they can still convey emotion in their performance by awakening their imagination to bring expression and emotional depth to their playing. In addition, in a concert situation, the imagination of the listener is very much at the disposal of the performer, to be shaped and influenced through sound.

We talk about performers “communicating the composer’s intentions” (i.e. paying attention to and acting upon directions in the score such as dynamics, tempo and expression markings, articulation, rests and pauses etc) or “conveying the story of the music“, but fundamentally I think as listeners we crave a performance which touches us personally. Listening to music is a highly subjective and personal experience – we’ve all had those ‘Proustian rush’ moments when a piece of music, or a single movement or even a phrase, provokes an involuntary memory, sometimes with physical side-effects such as goosebumps or shivers (physiologically, this is the result of the release of Dopamine, the brain’s “reward” neurotransmitter). Sometimes we want to feel uplifted or transported by music, taken us out of ourselves and the mundanity of everyday life to another place, to experience something touching the spiritual or transcendent. Such moments, and the memory of them, are very special and individual.

Occasionally one is at a concert where a very palpable sense of collective concentration can be felt in the auditorium. This occurs when the performer creates an intense communication between music and listener. I experienced it, along with the rest of the Wigmore Hall audience, at a performance of Beethoven’s last three sonatas by the Russian pianist Igor Levit in June 2017. The sense of concentrated listening and suspense was extraordinary. How did Levit achieve it? I’m not sure…. a combination of exquisite tone control, musical understanding and the sheer power of the music itself.

Most people like music because it gives them certain emotions such as joy, grief, sadness, and image of nature, a subject for daydreams or – still better – oblivion from “everyday life”. They want a drug – dope -…. Music would not be worth much if it were reduced to such an end. When people have learned to love music for itself, when they listen with other ears, their enjoyment will be of a far higher and more potent order, and they will be able to judge it on a higher plane and realise its intrinsic value.

– Igor Stravinsky

Dining With Music

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

Whim W’Him Contemporary Dance company in La revue du cuisine (2015)

As you peek around the corners of the repertoire, there are a few pieces that reflect the daily concern with Dining. There are works that set recipes, works that show the activities in a kitchen, works that show the procession of the courses, and one that gives you the ambient sound of a large kitchen. Let’s explore!

Martinů’s La revue de cuisine (1927) was still a favourite of its composer some 50 years later. It was a one-act jazz ballet about a love triangle in the kitchen between Pot, Lid, and the adventurous Whisk to which Pot has become enamoured. ‘The forthcoming marriage between Pot (Le chaudron) and Lid (Le couvercle) is jeopardised by the adventurous Whisk (Le moulinet) to whose magic Pot has succumbed. Pot is so captivated that Lid falls off him and rolls into a corner of the kitchen. Now Dishcloth wants to seduce Lid but order loving Broom to challenge Dishcloth to a duel, which delights Whisk. The two irritated combatants fight to the bitter end. Whisk makes eyes at Pot once more but now Pot longs for Lid, but Lid is nowhere to be found. The shadow of an enormous foot appears suddenly and with one kick propels Lid out of his corner. Broom leads him back to Pot, while Whisk and Dishcloth break out into a wild dance of joy.’ Despite this wildly interesting synopsis, the work has rarely been performed as a ballet in its entirety but has had a much more successful life as a suite. One recent version in 2013 moved the scenario to that of a traveling circus. The ballet score was revised and reconstructed by Christopher Hogwood after the full score was found in the Paul Sacher Foundation Archives.

Darius and Madeleine Milhaud on their wedding day, 1925

French composer Darius Milhaud (1895-1974) left France in 1940 when the Germans invaded and took up a post at Mills College in California. One of the changes that the Milhaud family experienced in America was the lack of household help. Cooks and maids were no longer available in war-time America. Milhaud paid tribute to his wife in 1944 in La Muse ménagère (The Household Muse), which recognizes his wife Madeleine’s ingenuity in having to take up household tasks during their time in the United States, where, as Milhaud noted, ‘servants receive higher wages than university professors.’ Her whirlwind kitchen activities are covered in the movement entitled La cuisine.

Jennie Tourel and Leonard Bernstein at a recording session, 1960

A ‘song cycle of recipes’ takes Emile Dumont’s 1899 cookbook La Bonne Cuisine Française (Tout ce qui a rapport à la table, manuel-guide pour la ville et la campagne) (Fine French Cooking “Everything That Has to Do with the Table, Manual Guide for City and Country”) as the text source for Leonard Bernstein’s 1947 work. Written for singer Jennie Tourel, it sets the recipes for Plum Pudding, Ox Tail, a Turkish dish of Tavouk Guenksis, and closes with a recipe for ‘Rabbit at Top Speed.’

Kitchen in Chateau d’Orion

In his 1961 work Grand Concerto Gastronomique for Eater, Waiter, Food and Large Orchestra, Op. 76, English composer Malcolm Arnold wrote a 6-part memorial to a great dinner. Written for the Hoffnung Festival in 1961, the work involved the actions of an off-stage chef and two on-stage actors (the Eater and the Waiter). The Prologue, with its fanfares and ‘comic gestures’ signals the beginning of the action: the Eater and the Waiter enact a ‘ceremonial napkin display’ and the meal is on. The second movement, Soup (Brown Windsor), is both ‘thickly scored and unappealing’, rather like the soup. It is in the third movement, Roast Beef, that the Englishness comes out. The movement may be short, but the performance instructions say that it must be ‘repeated and repeated slower and slower until all is finished’ and the plate of food must be ‘enormous.’ It is the Eater who determines how many repetitions of the march occur – choosing either to gulp everything down as quickly as possible or to savour every morsel, in the manner of Erik Satie’s piano piece Vexations (which 1 page of music is to be played 840 times).

This movement is followed by Cheese, and then the dessert course of Peach Melba and closes with Coffee, Brandy, Epilogue.

English composer Gavin Bryars’ work Cuisine (1993) was written for an installation at Chateau d’Orion, in Orion, France. The music was written to establish the ‘architectural acoustic’ of the space and ‘to animate the spaces in which the music was played.’

We all have our triumphs and failures in the kitchen. Each of these composers has chosen to memorialize something different for their kitchens: love affairs between the implements, the musicality of a recipe, the ceremony of a meal, or just the sound of the space.

Thursday, May 5, 2022

Vancouver pianist suffers heart failure during concerto performance, continues playing

By Sophia Alexandra Hall, ClassicFM

@sophiassocialsPrior to the concert, the audience was told the pianist had been experiencing a shortness of breath.

Last week, Georgian-American pianist Alexander Toradze was scheduled to perform two concertos with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra USA, based in Vancouver Washington.

However, the classical musician, who turns 70 next month, had been feeling unwell in the run up to the performance on Saturday 23 April. By the day of the concert, Toradze was struggling to walk unaided, so was accompanied onto the stage by Dr. Michael Liu, a medical doctor and board member of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra.

The audience had been warned in advance that although Toradze had tested negative for coronavirus, due to experiencing a shortness of breath there was a possibility the musician wouldn’t be able to perform.

However, the virtuoso pianist played through not one, but two concertos; first, Stravinsky’s Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments, followed by the main event, Shostakovich’s Second Piano Concerto. Toradze is recognised worldwide for his interpretation of Russian repertoire and studied at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow as a teenager.

His performances, which both took place during the first act, were met with enthusiastic applause, but unbeknownst to the audience – and at the time Toradze himself – the pianist had experienced acute heart failure while performing.

On Sunday, the day after the performance, Dr. Liu drove Toradze to PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center, where doctors told the pianist what had happened on stage. Toradze was meant to be playing with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra again tonight, but is instead being kept at the medical centre until his health stabilises.

Toradze recorded this video to reassure his fans and concerned members of the orchestra.

Describing the event as a “pretty memorable concert”, Toradze seems in good spirits and sends best wishes to all the musicians and his fans.

Saturday, April 9, 2022

MAKE MUSIC - NOT WAR!

Friday, April 8, 2022

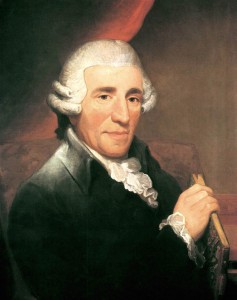

The Dark Childhood of Joseph Haydn

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

Joseph Haydn has entered music history as a jovial, grandfatherly figure with a reputation for a quick wit. Generations later, we still chuckle at the stories behind the Surprise Symphony or the Farewell Symphony. His famous good humor is all the more striking considering his often difficult upbringing.

Joseph Haydn has entered music history as a jovial, grandfatherly figure with a reputation for a quick wit. Generations later, we still chuckle at the stories behind the Surprise Symphony or the Farewell Symphony. His famous good humor is all the more striking considering his often difficult upbringing.

Joseph Haydn was born in the little town of Rohrau, Austria, on 31 March 1732, the second of twelve children. His father Mathias was a wheelwright by day and a folk musician by night. He was especially fond of accompanying himself on the harp singing folk tunes, and he would often encourage his family to sing along with him.

It’s no surprise that Joseph’s talent blossomed in this idyllic, naturally musical environment. That talent would soon change his life forever. When he was six, a distant relative named Johann Matthias Frankh visited Rohrau. Frankh was a schoolmaster and choirmaster in the town of Hainburg, and he thought that Joseph would do well to become his apprentice. Joseph’s parents hoped that such training would assist Joseph in becoming a clergyman, and so they agreed to send him away. Accordingly, Joseph Haydn left home at the age of six.

The Frankh family didn’t take very good care of their brilliant new charge. He frequently went hungry and he was beaten regularly. Later in life, he remembered being embarrassed at the dirty clothing the Frankhs forced him to wear. Nevertheless, he learned the basics of music: how to play the violin and harpsichord, and, more importantly for his immediate future, how to sing.

In 1739, not long after Joseph had arrived at the Frankh house, an important musician named Georg von Reutter came to town. Reutter was the director of music at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, and he was on a tour of the smaller Austrian cities, scouting out new talent for his cathedral choirs. (A steady supply of boys was needed, since every year a certain percentage of their high voices fell victim to puberty.) During this scouting trip, Reutter heard Haydn and was deeply impressed, offering him a position as a chorister. In the spring of 1740, Joseph made his second big move, arriving in Vienna at the age of eight.

He worked for nearly a decade at the cathedral as a chorister. He was steeped in church music, but he didn’t receive the systematic training in theory and composition that he craved. He eventually resorted to asking his father for money to buy the famous textbook Gradus ad Parnassum so that he could start to teach himself. He also still struggled to get enough to eat. But if he sang well enough, he was invited to perform at aristocratic parties, where he was fed.

He worked for nearly a decade at the cathedral as a chorister. He was steeped in church music, but he didn’t receive the systematic training in theory and composition that he craved. He eventually resorted to asking his father for money to buy the famous textbook Gradus ad Parnassum so that he could start to teach himself. He also still struggled to get enough to eat. But if he sang well enough, he was invited to perform at aristocratic parties, where he was fed.

By 1749, Haydn’s voice was starting to break. Apparently the Empress herself referred to his singing as “crowing.” Joseph didn’t help matters when he jokingly snipped off the pigtail of a fellow chorister. Ruetter threatened to cane Haydn for his insubordination. Haydn replied that he’d rather leave the choir than be so humiliated. Ruetter replied, “Of course you will be expelled…after you have been caned.”

So it was that a teenaged Joseph Haydn found himself humiliated, fired, and homeless. Luckily an acquaintance named Johann Michael Spangler invited the young genius to share (cramped) quarters with him, his wife, and baby son. His lodging secured, Haydn started working as a freelance musician, finally gaining a certain level of control over his life after years of lonely nights, tiny meals, and hard teachers.

Haydn was clearly more than a great composer or a quick wit. He was a survivor.

.jpg)

.jpg)