by

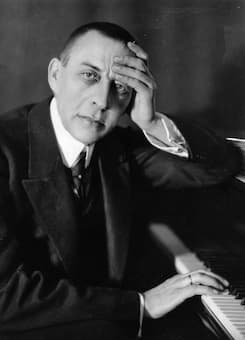

Sergei Rachmaninoff

You have to hand it to composer Sergei Rachmaninoff—his three symphonies, the Symphonic Dances, four piano concertos, and the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini are all written in minor keys. Other favorites, perhaps less frequently performed, are also in minor keys. Is there a reason?

Born in 1873, a leading piano virtuoso, composer, and conductor, Rachmaninoff became one of the last major figures of Russian romanticism. As a youngster, he began piano by the age of four, and displayed uncanny talent but he also experienced emotional ups and downs over his relationships and the successes or failures of his music. He lost two of his sisters, one to diphtheria and the other to pernicious anemia, and his father left the family.

The first performance of his Symphony No. 1 in D minor in 1897, a fiasco, led to scathing and caustic reviews. Rachmaninoff, overcome with despair, descended into a depression that lasted four years. The piece was never performed again during his lifetime. It is now said that the conductor of the premiere, Glazunov, was not only incompetent but also drunk at the time of the premiere.

By 1900 Rachmaninoff was paralyzed with self-doubt and unable to compose. After professional help, his creative juices were rekindled. The Piano Concerto No. 2, completed in 1901 and performed by Rachmaninoff himself, was a success and led to a Glinka Award. During the early 1900s Rachmaninoff, successfully toured the US, and lived in Germany for a time.

The Russian Revolution in 1917 caused great turmoil for the family. His estate was confiscated. Trying to keep his family safe from the bombardments, plagued with financial difficulties, he and his family left Russia and moved to New York. The self-imposed exile resulted in a wrenching time for the composer. The family after all relied on his income as a piano soloist and as a conductor. He performed 70 concerts during his tour of America during the 1922-23 season alone. Hence his compositional output was minimal—just six pieces from 1918-1943.

Arguably one of Rachmaninoff’s most famous pieces The Prelude Op. 3 No.2 is in C# minor and launched Rachmaninoff’s career after he performed this piece in 1892. Composers believe that particular keys evoke discernable and unique feelings. On the piano, this key uses many of the black keys with its slow chords, and one senses anxiety and tension from the beginning. There is a story that the inspiration for this work was a dream Rachmaninoff experienced: Set at a funeral where the coffin is prominently placed, he approaches the coffin, and to his horror he sees himself inside! That calls for a minor key!

Arguably one of Rachmaninoff’s most famous pieces The Prelude Op. 3 No.2 is in C# minor and launched Rachmaninoff’s career after he performed this piece in 1892. Composers believe that particular keys evoke discernable and unique feelings. On the piano, this key uses many of the black keys with its slow chords, and one senses anxiety and tension from the beginning. There is a story that the inspiration for this work was a dream Rachmaninoff experienced: Set at a funeral where the coffin is prominently placed, he approaches the coffin, and to his horror he sees himself inside! That calls for a minor key!

Let me draw your attention to a few other works in minor keys.

In 1893, deeply affected by the death of Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff composed his Trio Élégiaque No. 2 in D minor Op. 9 in Tchaikovsky’s memory, a piece filled with grief and anguish. The repeated descending notes in the first movement in the piano are decidedly morose with heart-rending cello and violin lines. The movement builds to a feverish climax and then as if spent, the music slows. A poignant melodic section accompanied by palpitating strings interrupts. A brief return to the agitated music precedes fading away in gloom.

The Cello Sonata in G minor Op.19 from 1901, was one of the first works Rachmaninoff wrote once he emerged from his stupor. How fortunate for cellists. It’s a gorgeous piece extremely tender and lyrical but fiendishly difficult for the pianist. Dedicated to the brilliant cellist Anatoliy Brandukov the first movement opens hesitantly, without a clear rhythm, but a passionate, breathless melody ensues, followed by a turbulent and foreboding scherzo. The four-movement piece includes a ravishing slow movement and a triumphant and massive finale. Perhaps imitating Rachmaninoff’s monumental personal journey?

Variations on a Theme of Corelli Op.42 is a set of 20 variations, for the piano. All but two variations are in D minor (the 14th and 15th are in D-flat major.) The theme is actually La Folia used by Corelli when he composed his Sonata for Violin and Continuo in 1700, which incorporates 23 Variations also in D minor. Rachmaninoff dedicated his variations to his friend esteemed violinist Fritz Kreisler. It begins in a stately fashion but the piece soon manifests Rachmaninoff’s style—melodies that remind us of his Paganini Variations, dark full passages like in his symphonies, virtuoso sections with big chords and octaves, and suspenseful moments with unpredictable rhythms and harmonies. Rachmaninoff’s originality is impressive and it takes a superb pianist to bring these elements to the fore.

The Isle of the Dead Symphonic Poem Op. 29 is composed in A minor. The piece was inspired by the Swiss symbolist artist Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead in a black and white rendition. Dark water, a barren island, craggy rocks, haunting hallucinations of a coffin, cemeteries, mourning, and the ancient chant of the dead Dies Irae recurs and alludes to death. The piece had to be in a minor key! It begins ominous, in the low strings, in the unusual and unsettling meter of a slow 5/8. The tension rises to an epic climax punctuated by multiple cymbal crashes. Chilling. Slowly unraveling, the piece returns to the dirge in darkness.

Ultimately Rachmaninoff had reason in his life to resort to minor keys to express his many disappointments and tragedies. And yet there is an infinite inventiveness in his music, which never fails to move us.