by

The young Brahms

In 1900, when Boston’s Symphony Hall was being built, Philip Hale, a distinguished American music critic working for the Boston Herald, suggested that a sign should be fitted over the central doorway reading, “Exit in case of Brahms”! Hale’s message is clear, if Brahms is on the program, run away as quickly as you can. We rightfully might dismiss Hale’s suggestion as sour grapes; however, at the turn of the twentieth century music criticism was not alone in expressing a pejorative and highly negative opinion of Brahms. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote: “I played over the music of that scoundrel Brahms. What a giftless bastard! It annoys me that this self-inflated mediocrity is hailed as a genius.” Hugo Wolf suggested, “The art of composing without ideas has decidedly found in Brahms one of its worthiest representatives.” Gustav Mahler, after his first composition failed to win a prize, with Brahms at the head of the selection committee, wrote “I have gone through all of Brahms pretty well by now. All I can say of him is that he’s a puny little dwarf with a rather narrow chest.” And Benjamin Britten quipped, “It’s not bad Brahms I mind’, it’s good Brahms I can’t stand.” Friedrich Nietzsche suggested that the music of Brahms “perspires profusely,” and to George Bernard Shaw it sounded, “extremely constipated.” These exaggerated visceral reactions and earthy comparisons to bodily functions are not merely the result of professional jealousy or the effect Brahms’s music had on his critics. Rather, the vicious and personal nature of the criticism suggests that the real target was Brahms himself. However you look at it, there is a clear disconnect between the way Brahms was perceived at the turn of the 20th-Century, and the way we think of him today. Instead of giving you a play by play of the labored gestation of the Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 — and indeed, Brahms spent nearly twenty-one years completing this work — let us briefly untangle the mechanism that fused Brahms the man and Brahms the composer into an idealized and naïve package for easy consumption.

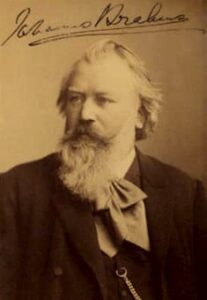

Johannes Brahms

Photographs of the composer, taken by Maria Fellinger in the 1890’s, show a kind and gentle old man with flowing beard, highly reminiscent of imagery associated with Santa Claus. In one of these extraordinary photographs, Brahms is sitting in his personal library surrounded by books and musical scores. And this is exactly how we think of Brahms today; a grand, old master of an extended Austro-German musical traditions, exclusively absorbed with musical history and knowledge, and defending his way of thought against all corrupting influences of a rapidly encroaching and changing world. This particular way of thinking about Brahms was actively shaped and promoted in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s. Musicologist working at Universities in the United States and Europe, together with historians and politicians were, after the horrors of WW2 and the atrocities committed by Nazi Germany, actively searching for a kinder and gentler German. And a German Santa Claus figure whose only goal in life was to compose, perform and live in the service of music did fit that image perfectly. Yet, Brahms was hardly a nice and gentle soul. He had a strong dislike for the French, the Russians, the English and the Americans, really anything that would pose a threat to German cultural and political supremacy. Paired with a strong dose of pessimism as to the future of German culture, he was highly patriotic and militantly opposed to foreign influences. He hated almost everything having to do with technology, especially despised cameras and bicycles, and his relationship with women was ambivalent at best. He publicly embarrassed them whenever he could — telling dirty jokes or making sexually explicit comments — and only began to show real interest in them once they were married to somebody else. In addition, Brahms utterly dominated the Viennese musical scene in terms of administration and governance. He was a highly active member of the most important committees, legislative boards and funding commissions and every appointment at the Conservatory, the University or private music institutions were subject to his approval or venomous contempt. When Hans Rott, a highly talented composer and the natural musical link between the symphonic works of Anton Bruckner and Gustav Mahler submitted the first movement of his E-major Symphony to a composition contest, Brahms told him that he “had absolutely no talent whatsoever, and that he should give up music altogether.” Unable to deal with this rejection, Rott bought a revolver and threatened a passenger during a train journey, claiming that Brahms had filled the train with dynamite. Rott was eventually committed to a mental hospital, where he died at age 25.

The charges leveled against Brahms by his contemporaries were made in the context of his abrasive personality, his radical nationalist political position, his professional influence, and against his music, which was seen as old-fashioned, introvert, dry and complex. Many composers and critics wanted Brahms and his music to be swept away by a new wave of music, commonly referred to as the “music of passion.” Proponents of Brahms’s music stubbornly and innocently maintained that his music came from intuition, that is, he composed music exclusively for the sake of expressing music. This conception clearly clashed with those who promoted compositions that sought overt connections to extra-musical elements — be it poetry, literature or architecture — seeking a programmatic content that involved a process of conscious reflection. Ironically, Brahms’s passions — which are best understood in terms of his personality and convictions — are clearly present in his music; he simply did not feel like providing written explanations. His patriotism, aggression, yearning, ambivalence towards women — frequently juxtaposing the idealized image of the Virgin Mary against the common prostitute in the street — and even his “constipation” are essential aspects of his compositions. So let’s not get stuck in some artificially constructed musical Disneyland but rather discover what makes the music of Brahms one of the most powerful, tightly strung, and abrasive musical expressions of the 19th century.