Background as an Organist and Performer

Muzio Clementi

Born in 1752, Italian composer Clementi showed his musical talent at an early age. Not only did he begin composing and writing an oratorio at the age of 13, but he was also hired as an organist of the parish church of San Lorenzo in Dámaso. However, he didn’t work for the church for a long time. Instead, in 1766, he was taken to England by Sir Peter Beckford. The following seven years, Clementi stayed at one of Beckford’s estates, Stepleton House, where he gave his first public performance. The performance was successful, and the audience was impressed with his playing.

His Encounter with Mozart

Clementi left the estate when he turned 22 years old. His reputation as a performer quickly developed as he toured around London and later all over Europe. When he was in Vienna in 1781, he was invited by Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II to contest with Mozart. The composers were asked to improvise and perform excerpts of their works. Even though the contest was declared a tie, Mozart and Clementi had very different impressions of each other. Clementi was impressed by Mozart’s performance. One of Clementi’s students, Ludwig Berger, recalled what Clementi said of Mozart:

“Until then I had never heard anyone play with such spirit and grace. I was particularly overwhelmed by an adagio and by several of his extempore variations for which the Emperor had chosen the theme, and which we were to devise alternately.”

Stepleton House

However, Mozart was not impressed by Clementi’s playing at all. In one of his letters to his father, Mozart mentioned that Clementi’s playing was a “mere mechanic” and

“Clementi is a charlatan, like all Italians. He marks a piece presto but plays only allegro.”

Although Mozart remained negative of Clementi, Clementi was influential to many composers and pianists even to this day. On the other hand, Beethoven looked highly upon Clementi and his compositions. He encouraged his nephew, Karl van Beethoven, to learn Clementi’s works. Beethoven said, “They who thoroughly study Clementi, at the same time make themselves acquainted with Mozart and other composers; but the converse is not the fact.”

The “Newer School of Technique on the Piano”

Clementi has been known as the “Father of the Piano.” Through his 110 piano sonatas, Clementi expanded and showcased the capabilities of the pianos, as well as exhibited many virtuosic passages and demanding skills required to execute his works.

Ignaz Moscheles once wrote that Clementi founded the “newer school of technique on the piano.” Moscheles was among one of the students of Clementi. Others included Johann Baptist Cramer, Therese Jansen Bartolozzi, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Ludwig Berger (teacher of Felix Mendelssohn), and John Field.

Influences on the History of Piano-Making

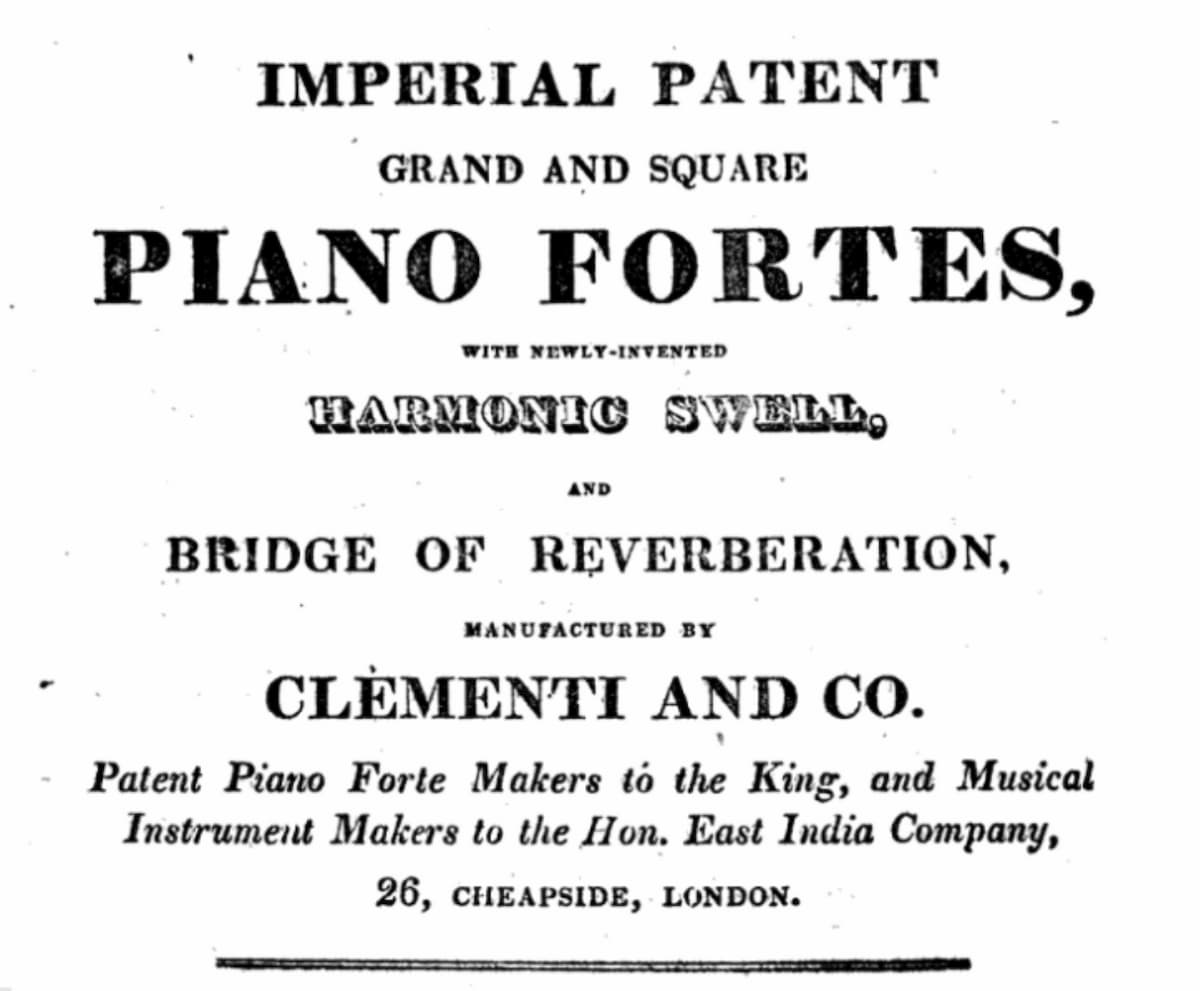

This Father of the Piano influenced piano history in more than just as a composer, a performer, and a pedagogue. Clementi was also known as a clever businessman. Clementi was involved in both music publishing and piano manufacturing. In 1798, when he was 45 years old, he took over Longman and Broderip and began a publication line, “Clementi & Co., & Clementi, Cheapside.”

Clementi brought significant improvements to the design of pianos, and many remained the piano standard. In 1810, Clementi almost completely stopped performing and devoted most of his time to composing and piano making. One of his last compositions, Gradus ad Parnassum, is a set of 100 studies published in 3 volumes. The studies are short but cover both technical and interpretative skills that deserve more attention from piano lovers.

Besides Gradus ad Parnassum and the 110 piano sonatas, Clementi’s Capriccios are equally charming. His output of Capriccios spanned over his career, and among them, the two Capriccios in op.34 display many expressive and improvisatory elements in Clementi’s music. lementi, a legendary performer, composer, educator, publisher, and piano manufacturer, lived a prolific life and is well deserved to be called the Father of Piano. Yet, he also was a conductor who founded the Philharmonic Society of London (which later became the Royal Philharmonic Society in 1912). He also wrote a few symphonies and chamber works, including Symphony No.3. It is nicknamed “the Great National,” and Clementi used God Save the King (National Anthem of the United Kingdom) in various movements.