By Georg Predota, Interlude

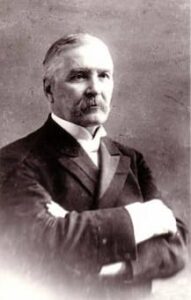

Mykola Lysenko

The political conditions in 19th century Europe spawned a rapid growth of Nationalism and Patriotism across the continent. “The pride of conquering nations and the struggle for freedom of suppressed ones gave rise to strong emotions that inspired the works of many creative artists.” We are well aware of countless composers working within this forceful stream of romanticism, ranging from Smetana and Dvořák in the Czech Lands, Edvard Grieg in Norway, Jean Sibelius in Finland, Elgar and Delius in England, Albeniz, Granados and Falla in Spain, and a whole Russian national school established by Mikhail Glinka.

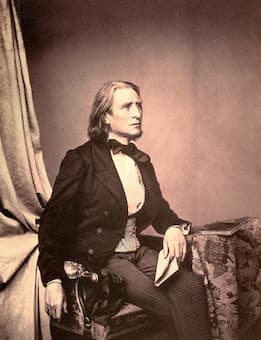

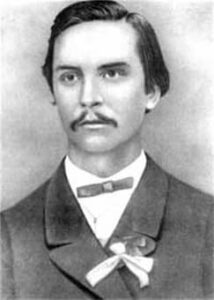

Mykola Lysenko, 1869

As in many other parts of Europe, the emergence of a national spirit in Ukraine resulted in a movement that cultivated popular Ukrainian culture. At the head of this Ukrainian movement for national musical identity we find Mykola Lysenko (1842-1912), widely considered the father of Ukrainian Music. “Beyond providing the inspiration for a national compositional school and founding numerous choirs across the proto-Ukrainian countryside, he is also a national hero whose music academy in Kyiv was a hub for intellectuals, poets and musicians.” Lysenko composed his patriotic hymn in 1885, during a period when Ukrainian culture and language was once again suppressed by the government of Imperial Russia. Lord, O the Great and Almighty,

Protect our beloved Ukraine,

Bless her with freedom and light

Of your holy rays.

With learning and knowledge enlighten

Us, your children small,

In love pure and everlasting

Let us, O Lord, grow.

We pray, O Lord Almighty,

Protect our beloved Ukraine,

Grant our people and country

All your kindness and grace.

Bless us with freedom, bless us with wisdom,

Guide into kind world,

Bless us, O Lord, with good fortune

Forever and evermore.

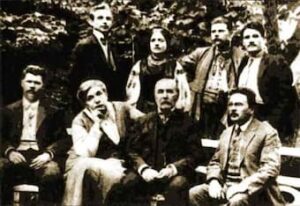

Mykola Lysenko among the Ukrainian civic leaders in Kharkiv

Ukraine has long struggled for independence, with the borders shifting countless time as different conquerors fought over a land rich in natural resource and culture. A short-lived revolution in 1919 was brutally suppressed and the Soviet occupation inflicted one tragedy after another on the Ukrainian people. During the famine of the 1930s, millions of Ukrainian peasants starved to death because of the criminal policies of Joseph Stalin. We must add “the Nazi occupation of Western Ukraine, when the Final Solution was first implemented in cities whose wealth and cultural standing depended entirely on the vast Jewish population – cities like Lviv or Ivano-Frankivsk; the deportation of the Hutsul people in the 1930s and the deportations of the Crimean Tatar population from the beautiful Crimean peninsula, at the command of various Russian heads of state, starting with the Tsars, repeated under Stalin and then once again in 2014 after the Russian occupation. And we all know about the atrocities being committed under Vladimir Putin right now.

Mykola Lysenko: Dumka-Shooma, Op. 18 (Natalya Pasichnyk, piano)

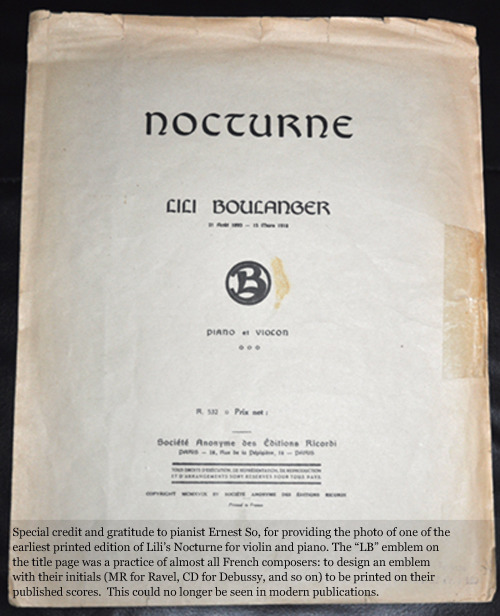

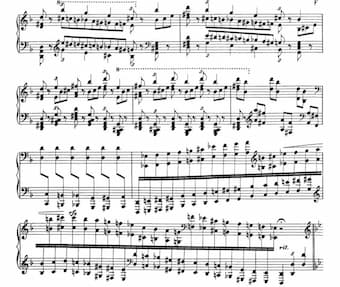

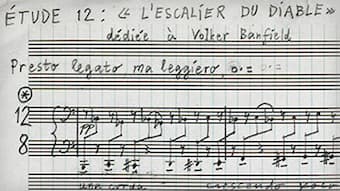

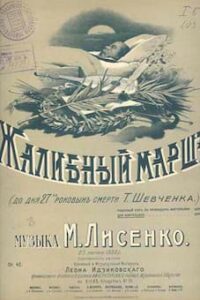

Lysenko’s music score

Lysenko was born in Hrymky, a village near the Dnipro River between Kyiv and Dnipropetrovsk. He came from an old aristocratic family, tracing his lineage back to the Cossacks of the 17th century. Received his rudimentary musical education from his mother, he left for boarding schools in Kyiv and then Karkiv, and he took piano lessons with Panochini and studied theory with Nejnkevič. From 1860 Lysenko studied at Kharkiv University and Kyiv University, joining a number of Ukrainian student societies and church choirs. Ukrainian folk music became his passion, and he began “his life-long ethnographical work of collecting and studying Ukrainian folksong.” Earlier, as a child, he had been deeply impressed by the music of peasant singing, and his nationalist sympathies were greatly stimulated by a volume of poetry by the Ukrainian national poet Taras Shevchenko. Lysenko had been given this volume of Shevchenko’s poetry by his grandfather, and his imagination was fired by words of freedom for the oppressed, especially Ukrainians. A prophetic figure in the Ukrainian Enlightenment, Shevchenko expressed the plight of the Ukrainian people in poetry in the early eighteenth century and “even today holds the status of national hero, as a symbol of the spirit of resistance.” When Shevchenko’s body was brought to Ukraine after his death in 1861, Lysenko, at the age of 19, was a pallbearer at the poet’s funeral.

Mykola Lysenko: Elegy in Memory of Shevchenko (Solomia Soroka, violin; Arthur Greene, piano)

Mykola Lysenko with teachers of Lysenko Music and Drama School

After graduating in 1865 with a degree in natural science, Lysenko entered the civil service as an arbitrator in land-ownership claims for former serfs, but two years later this particular job was made redundant. As such, he was looking to further his musical studies and he attended the Leipzig Conservatoire, with his most prominent teachers including Ferdinand David, Ignaz Moscheles, Carl Reinecke and Ernst Wenzel. In Leipzig, Lysenko began to fully understand the importance of “collection, developing, and creating Ukrainian music rather than duplicating the work of Western classical composers.” In fact, he was determined to establish a Ukrainian national school of music, and to best express his fervent patriotic and political ideals through music. He returned to Kyiv in 1869 to work as a music teacher and conductor, and continued to collect, publish and study folk music. After taking orchestration lessons from Rimsky-Korsakov in St Petersburg between 1874 and 1876, Lysenko returned to Kyiv and was active as a private teacher before opening his own school of music and drama in 1904.

Mykola Lysenko, 1900s

Being a descendant of the 17th century Cossack leader Vovgura Lys, the story of “Taras Bulba” held special significance for Lysenko. The story of this romanticized historical novella by Nikolai Gogol featuring Taras Bulba and his two sons Andriy and Ostap going to war against Poland. Taras is eventually captured, nailed and tied to a tree and set aflame. Even in this state he calls out to his men to continue the fight. Lysenko worked on his opera Taras Bulba during 1880-1891, but it was his insistence on the use of Ukrainian for performance that prevented any productions during his lifetime. He steadfastly refused to allow the opera to be translated. He did play the score to Tchaikovsky, who reportedly “listened to the whole opera with rapt attention, from time to time voicing approval and admiration. He particularly liked the passages in which national Ukrainian touches were most vivid… Tchaikovsky embraced Lysenko and congratulated him on his talented composition.” As modern critic wrote, “The opera marks a great advance on the composer’s earlier works with its folklore and nationalistic elements being much more closely integrated in a continuous musical framework which also clearly shows a debt to Tchaikovsky. But the episodic nature of the libretto, which may be due to some extent to political considerations during its revision in the Soviet era is still a serious problem.

Grave of Mykola Lysenko

During his lifetime, Lysenko arranged roughly 500 folk songs, including both solos and choruses with piano accompaniment, and a-capella choruses. Focusing on the tonal and harmonic characteristics of Ukrainian folk songs, he “fashioned arrangement of various types of songs based on a specific Ukrainian cultural tradition.” In fact, Lysenko was adamant to clearly demonstrate the differences between the folk music of the Ukraine and that of Russia. He had been drawn to musical folklore from an early age, and made the first musical-ethnographic studies on the blind kobzar—an itinerant Ukrainian bard singing to his own accompaniment and playing a multi-stringed bandaura of kobza—Ostap Veresai in 1873. He expanded his research into other regions, and his ethno-musicological projects included a monograph on Ukrainian folk music instruments. In addition, Lysenko wrote over 120 art songs to lyrics of Taras Shevchenko as well as Lesia Ukrainka, Ivan Franko, Heinrich Heine, Oleksandr Oles, Adam Mickiewicz and others. A compilation of Lysenko’s works was published in 20 volumes in Kyiv between 1950 and 1959.

Mykola Lysenko monument

Lysenko was a capable concert pianist, and among his numerous compositions for the piano we find a sonata, two rhapsodies, a suite, a scherzo, and a rondo alongside a long list of smaller forms such as Songs without Words, nocturnes, waltzes, and polonaises. In these works he often uses the melodies and rhythms of Ukrainian folk songs, imbued with the musical style and spirit of Frédéric Chopin. Mykola Lysenko is acknowledged as the founding father of Ukrainian music, and during his lifetime he was at the center of Ukrainian cultural and musical life in Kyiv. He gave piano recitals and organized choirs for performances in Kyiv and tours through Ukraine in 1893, 1897, 1899, and 1902. On the occasion of a celebration marking 35 years as a composer, funds were raised that enabled him to open a Ukrainian School of Music “in opposition to the Russian Musical Society’s school in Kiev.” Lysenko inspired countless young Ukrainian musical minds, and his daughter Mariana followed in her father’s footsteps as a pianist, and his son Ostap also taught music in Kyiv.