From writing the world's best-loved soundtracks - such as Star Wars and Harry Potter - to conducting the Boston Pops, John Williams is one of today's musical giants.

1. The force is with him

Born on 8 February 1932 in Long Island, John Williams has composed some of the most popular and recognizable film scores ever, including Jaws, the Star Wars films, Superman, the Indiana Jones movies, E.T., Jurassic Park, Schindler's List, Saving Private Ryan and three Harry Potter instalments. He has won five Oscars, four Golden Globes, seven BAFTAs and 21 Grammys. With 48 Oscar nominations, he is second only to Walt Disney as most nominated person ever.2. Aspiring young musician

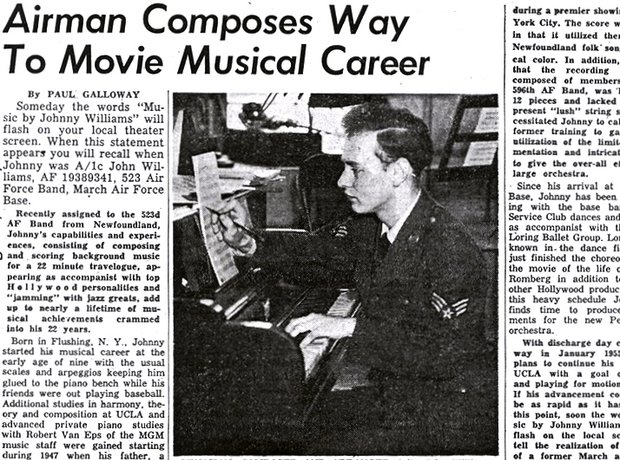

John Williams grew up in a musical family; his father was a jazz percussionist. Young John attended UCLA while studying composition privately with Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco. Drafted in 1952, Williams spent three years conducting and arranging music for the U.S. Air Force Band. After his service ended, Williams moved to New York City and entered Juilliard where he studied piano.3. Legendary piano riff

Williams worked as a pianist in jazz clubs and eventually studios, most notably for the brilliant Henry Mancini. 'Little Johnny Love Williams' played the famous piano riff on the groundbreaking Peter Gunn theme. Williams went on to be music arranger and bandleader for a number of albums for singer Frankie Laine.4. Composing TV classics

Williams returned to L.A. from New York. There he began working as an orchestrator at film studios with such legends from Hollywood's Golden Age as Franz Waxman, Bernard Herrmann, and Alfred Newman. He also developed his skills writing the music for hit 1960 TV shows, Gilligan's Island, Lost in Space, The Time Tunnel and Land of the Giants - pictured.5. Academy Award recognition

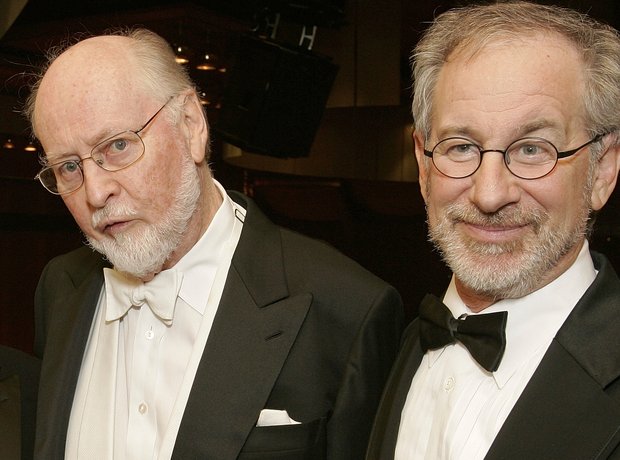

John Williams received his first Academy Award nomination in 1967 for Valley of the Dolls. He was nominated again for Goodbye, Mr. Chips. He won his first Oscar for musical direction for Fiddler on the Roof. High profile scores for 1970s disaster movies followed - The Poseidon Adventure, The Towering Inferno and Earthquake.6. An extraordinary partnership

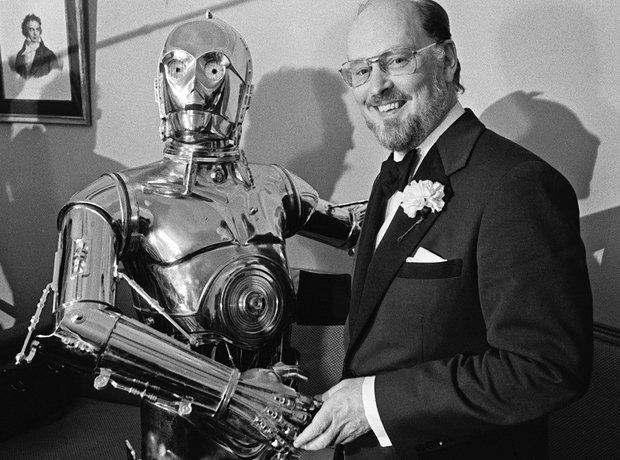

In 1974, a young director called Steven Spielberg approached Williams to compose music for his film, The Sugarland Express. They teamed up again the following year for Jaws. The threatening shark motif, two low notes played alternately on the tuba, has since become synonymous with sharks in general and danger at sea. Spielberg and Williams have gone on to work on more than 20 films together, most recently War Horse, Lincoln and The Adventures of Tintin.7. A galaxy far, far away...

Spielberg recommended Williams to his friend George Lucas, who needed a composer for Star Wars. Williams delivered a grand symphonic score in the style of Hollywood's swashbucklers of the 1930s and 1940s. The soundtrack remains the best-selling non-pop record of all-time - and Williams won another Oscar for Best Original Score. He was also nominated for the follow-up scores for The Empire Strikes Back and The Return of the Jedi.8. At the peak of his powers

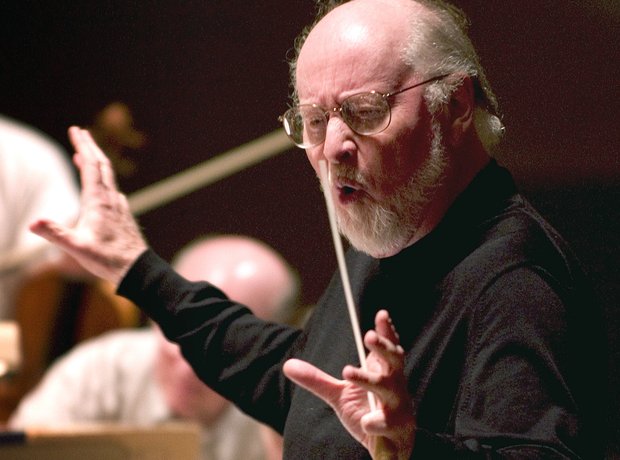

The late 1970s and early 1980s saw Williams at the peak of his powers and success. He scored Superman in 1978, followed by The Empire Strikes Back (1980), and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), created by George Lucas and directed by Spielberg. Williams' rousing Raiders March theme has defined the character of Indiana Jones and become a concert hall favourite in its own right.9. Boston Pops star

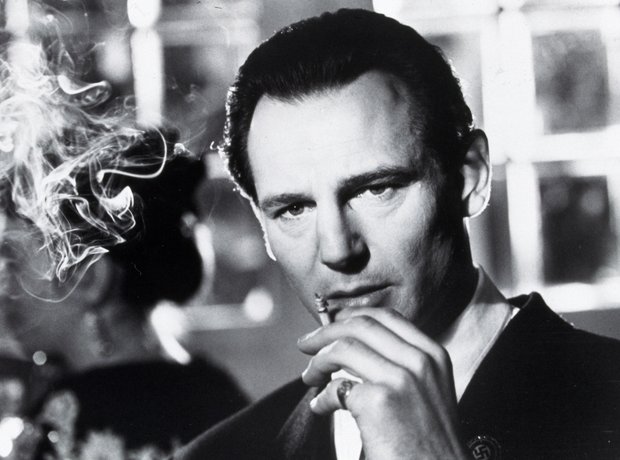

From 1980 to 1993, Williams was Principal Conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra. He is now its Laureate Conductor, leading the orchestra on several occasions each year, particularly during their Holiday Pops season and a week of concerts in May. He conducts an annual Film Night at both Boston Symphony Hall and Tanglewood.10. Schindler's List

Considered by many to be the finest film score of recent decades, Schindler's List followed hot on the heels of Spielberg and Williams' collaboration on Jurassic Park - and it couldn't be more different. When he first saw the film, the composer told the director: 'You need a better composer than I am for this film.' Spielberg replied, 'I know. But they're all dead!' For the soundtrack Williams, following Spielberg's suggestion, hired the great violinist Itzhak Perlman. The film's main theme, played with such passion and emotional intensity by Perlman, is heartbreakingly simple and touching. For Schindler's List, Williams won his fifth Oscar.

omposer John Williams awarded RPS Gold Medal...

... for introducing millions to orchestral music

‘He has dedicated his life to ensuring orchestral music continues to speak to and captivate millions of people worldwide.’

Internationally treasured composer , 88, is the recipient of this year’s RPS Gold Medal.

The legendary film maestro, who composed the enduring music for Star Wars, , and many more, won the coveted award at the 2020 Awards, for introducing millions to orchestral music.

His win, one of the highest honours in music recognising outstanding musicianship since 1870, was announced during a digital broadcast on 18 November featuring performances filmed at London’s .

Accepting the medal via video, Williams said: “To receive this award is beyond any expectation I could possibly have. For any composer to be able devote his or her life entirely to the composition of music is very fortunate indeed.”

Director Steven Spielberg presented a special congratulatory message to his long-time collaborator via video message, saying: “John, you have brought the classical idiom to young people all over the world through your scores, and through your classical training and your classical sensibilities. You are in the DNA of the musical culture of today.”

In his wonderful introduction to Williams’ win, which was determined by the RPS Board and Council and voted for by RPS members, RPS chairman John Gilhooly said:

“Some of us are born into classical music, never recalling a time without it. Others are drawn to its magic by the spell that orchestras cast in bringing soul, drama and humanity to motion pictures.

“The recipient of this year’s RPS Gold Medal has dedicated his life to ensuring orchestral music continues to speak to and captivate people worldwide in this way. Aged 88 and still at work, he is an international treasure, writing score after score of sophistication and impact, many transcendent of the films for which they were written.”

Elsewhere, cellist was presented with the Young Artists Award for “captivating listeners worldwide”.

Welsh soprano Natalya Romaniw received the Singer Award, while the Scottish Ensemble received the Ensemble Award for their innovation in their 50th birthday year.

(C) 2020 by ClassicFM London

Unlike many contemporary composers, John Williams is a household name, even among families who aren't classic music buffs. To date, his award stats seem inconceivable, even to the most aspiring of professional composers. They include 25 Grammy Awards, seven British Academy Film Awards, five Academy Awards, and four Golden Globe Awards (and more to come, we would imagine).

A well-published John Williams quote (filmtracks.com) states, "So much of what we do is ephemeral and quickly forgotten, even by ourselves, so it's gratifying to have something you have done linger in people's memories." Based on that statement, this famous musician, composer, conductor, and music producer must be one gratified human being.

John (Johnny) Williams II: The Basics

We can't post an Artist Spotlight without capturing some of the basic biographical details. But, as we know, there is so much more to any human than birth dates and accolades. Therefore, the second section of this post focuses on facts you may not know about one of the 20th/21st centuries' most famous and well-loved composers.

The Early Years

John (Johnny during his younger years) Towner Williams II was born on February 8, 1932, making him almost 90 years wise today. He was born in Queens, New York, to parents Esther (née Towner, hence his middle name) and Johnny Williams. His father was a talented jazz percussionist who played with the Raymond Scott Quintet. Later on, after the family's move to Los Angeles in 1948, his father worked as a recording artist and a studio musician for both radio and films.

Williams's mother was originally from Maine and grew up in a family that owned a department store. Her father was also a carpenter and cabinet maker. As a result, John Williams, the composer, felt his life exemplifies both the musicianship and the strong work ethic that defined his formative years and family culture.

As is the way of many professional composers, Williams quickly became poly-instrumental. He began playing the piano at age six. By the time he left grade school, Williams was proficient on the bassoon, cello, clarinet, trombone, and trumpet. Eventually, Johnny-now-John attended UCLA, where he studied composition.

Williams' later years

In 1951, John Williams got drafted into the military, where he served in the U.S. Air Force Band as a pianist, brass player, and conductor. Upon his release from the service in 1955, he was accepted into Julliard. At first, Williams planned to become a concert pianist but eventually turned his sights to composition. He continued his composition studies at the Eastman School of Music and, upon graduation, Williams began working as an orchestrator in film studios.

That initial post-graduate job led to Williams's career as a world-renowned film score composer. However, it's impossible to narrow down his "best-known works" because the entire list is recognizable, including:

Jaws (1975)

Superman - The Movie (1978)

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

Jurassic Park (1993)

Schindler's List (1994)

Seven Years in Tibet (1997)

Saving Private Ryan (1998)

The first three Harry Potter films (2001, 2002, and 2004)

All of the Star Wars films

(Wikipedia's complete list of compositions by John Williams)

We could go on, but you get the point. He also served as music director and laureate conductor of one of the country's treasured musical institutions, the Boston Pops Orchestra.

In our post, Insights From the World's Best Film Score Composers, we quoted John Williams saying, "I think the biggest single mission perhaps of the filmmakers and myself is to try to seek universalisms in the story, in the music, and in the emotions." (Source: Gramaphone). His laudable career exemplifies John Williams's ability to do just that.

10 Fun Facts

Now, as promised, we'd like to break away from the basic details and leave you with ten fun facts you might not have known about John Williams.

He's been nominated for 52 Academy Awards, making him the second-most nominated person after Walt Disney.

You can hear some of his early professional piano playing in the movies "Some Like it Hot (1959)" and "To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)."

Williams "allowed" Steven Spielberg to play clarinet, which he'd learned to play in high school in the band street scene. The dailyjaws.com website quotes Williams saying that Spielberg "added the right amateur quality to the piece" (sorry, Steven).

He paid his way through graduate music school, working as a nightclub jazz pianist and a bandleader called "Little Johnny Love."

In an interview with businessinsider.com, Williams admitted that he's never seen a single "finished" version of the Star Wars Films.

Technology is not his thing. Williams composes his scores at a desk with a pencil and paper, with his adjacent Steinway piano as a companion. John Williams has this to say about technology, "I have not evolved to the point where I use computers and synthesizers. First of all, they didn't exist when I was studying music, and luckily, mercifully, I have been so busy in the interim years that I haven't had time to go back and retool. And so my evolution, in very practical terms, i.e. piano and pencil and paper, has not changed at all." (Grunge)

John Williams's son, Joseph, was the lead singer of the band Toto, most famous for their songs, "Africa" and "Rosanna."

While best known for his film scores, a composer is a composer through and through. Williams has also composed concert hall performances that include two symphonies and various concertos for horn, cello, clarinet, flute, violin, and bassoon. Watch Yo-Yo Ma performing Williams's Concerto for Cello and Orchestra.

The iconic first three notes of the Jaws theme song (which Spielberg thought were a joke at first) have become the most famous musical introduction in history after the beginning of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

Two of his first Academy nominations were for movies you've probably never heard of: Valley of the Dolls (1967) and Good-Bye, Mr. Chips (1969).

At a sharp and still-composing 89 years old, John Williams is a musician, composer, producer, and conductor who deserves every bit of the respect and accolades he's received. We look forward to what this soon-to-be nonagenarian composes next.