Julie von Breuning

Beethoven’s friendship with Stephan von Breuning (1774-1827) lasted a lifetime. We will meet him in more detail in another episode. For now it suffices to say that Beethoven’s Violin Concerto was dedicated to him. Concurrently, Beethoven fashioned a piano transcription, which is dedicated to Julie von Breuning. Born Julie Vering, she was the daughter of Beethoven’s physician Gerhard von Vering, and an excellent pianist with whom Beethoven enjoyed playing duets. It has been suggested that this double dedication was a wedding present to the von Breunings, who had been married in April 1808. Incidentally, the arrangement for piano and orchestra was published at least half a year before the original version for violin and orchestra. Some commentators have questioned the idiomatic merits of arranging a violin concerto for the piano, but “it could be argued that the importance of the work lies not in the violin virtuosity of the solo part, but rather in the musical qualities that transcend the instrumental setting.” This little anecdote has a rather sad ending, however, as Julie von Breuning died at age 19 after less than a year of marriage. The official cause was given as “hemorrhage of the lungs brought on by the imprudent use of cold foot baths.”

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna took place from 18 September 1814 to 9 June 1815 and intended to reestablish something of the European order that had existed before the conquests of Napoleon. Under the chairmanship of Prince Metternich, leaders of the major European states discussed not only political matters, but also engaged in social activities. For one, they attended a grand Beethoven concert on 29 November 1814. This concert had already been postponed three times, but eventually the newspaper reported on 30 November, “At noon yesterday, Hr. Ludwig v. Beethoven gave all music lovers an ecstatic pleasure. In the Redoutenssal he gave performances of this beautiful musical representation of Wellington’s Battle at Vittoria, preceded by the symphony, which had been composed as a companion piece. Between the two works an entirely new cantata, Der glorreiche Augenblick.” The Vienna City Administration had commissioned the work, and Beethoven set a text fashioned by Aloys Weissenbach, a former army doctor. The audience included the Empress, the Tsarina of Russia, the King of Prussia and other dignitaries. The concert was twice repeated in December 1814, and the dedication of the Cantata dutifully reads “To the Congress of Vienna.”

Count Franz von Oppersdorff

In 1806, Beethoven spent an uneasy summer at the country estate of his patron, Prince Lichnowsky. The Prince and Beethoven had gotten into a heated argument over a request to perform for a group of visiting French Soldiers. According to the composer Ferdinand Ries, it was Count Franz von Oppersdorff who stepped between the two quarreling men just in time to prevent Beethoven from smashing a chair over Lichnowsky’s head. Beethoven abruptly departed the Lichnowsky estate and spent the rest of his summer holiday at the Oppersdorff estate. The Count maintained a private orchestra and to honor his famous musical guest, he arranged for a performance of Beethoven’s Second Symphony. Beethoven was pleased, and Oppersdorff commissioned a new symphony from Beethoven. Since Beethoven had been working on his Fifth Symphony at the time, he initially might have intended it in fulfillment of the commission. In the end, Beethoven presented his Fourth Symphony, a work that was essentially complete before the commission, to Oppersdorff. Oppersdorff paid 500 guilders for the work, and five month later commissioned Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, paying another 500 guilders. That work, however, is jointly dedicated to Count Razumovsky and Prince Joseph Franz von Lobkowitz.

Beethoven’s letter to Franz Oliva

Franz Oliva (1786 – 1848) was a banking clerk at Offenheimer and Herz, and he served Beethoven as a part-time secretary from about 1809 until December 1820, when Oliva moved to St. Petersburg. Oliva occasionally served as Beethoven’s business representative, receiving funds from various publishers. Beethoven and Oliva got on well together, and he personally delivered a letter from Beethoven to Goethe. In 1809 Beethoven dedicated the Op. 76 Variations to him, but predictably the relationship ran into trouble on various occasions. Beethoven warned his landlord Pasqualati, “Do not have much to do with the rascal Oliva. I am glad that this connection, which was only formed through necessity, will hereby be entirely broking off.” After Oliva’s departure for St. Petersburg, the Austrian Government, under threat of imprisonment, demanded his return to Vienna. Oliva would have none of it and took a wife and residency in St. Petersburg. When the biographer Otto Jahn contacted Oliva’s daughter for correspondence between Beethoven and her father, he was curtly told that a fire had destroyed all documents.

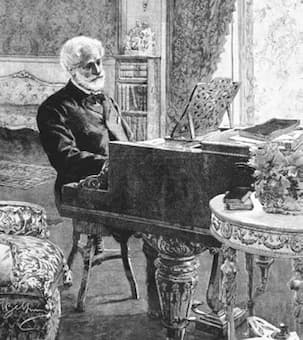

Verdi described the setting of the “Ave Maria” as Scala enigmatica armonizzata a Quattro voci miste (Enigmatic scale, harmonized for four mixed voices). This enigmatic scale spans an octave and rises by a semitone and by an augmented second. It is followed by three whole tone and two semitones. It descends with two semitones followed by one whole tone and an augmented second. From there a semitone, the original augmented second, and finally a semitone concludes the descending version of Verdi’s enigmatic scale. The scale is first heard in the bass, both ascending and descending, and then in the alto, tenor and the soprano. It sounds like a harmonic and contrapuntal exercise, and originally it was not part of the Quattro pezzi sacri, but eventually the publisher Ricordi included it in the set.

Verdi described the setting of the “Ave Maria” as Scala enigmatica armonizzata a Quattro voci miste (Enigmatic scale, harmonized for four mixed voices). This enigmatic scale spans an octave and rises by a semitone and by an augmented second. It is followed by three whole tone and two semitones. It descends with two semitones followed by one whole tone and an augmented second. From there a semitone, the original augmented second, and finally a semitone concludes the descending version of Verdi’s enigmatic scale. The scale is first heard in the bass, both ascending and descending, and then in the alto, tenor and the soprano. It sounds like a harmonic and contrapuntal exercise, and originally it was not part of the Quattro pezzi sacri, but eventually the publisher Ricordi included it in the set.