by Maureen Buja, Interlude

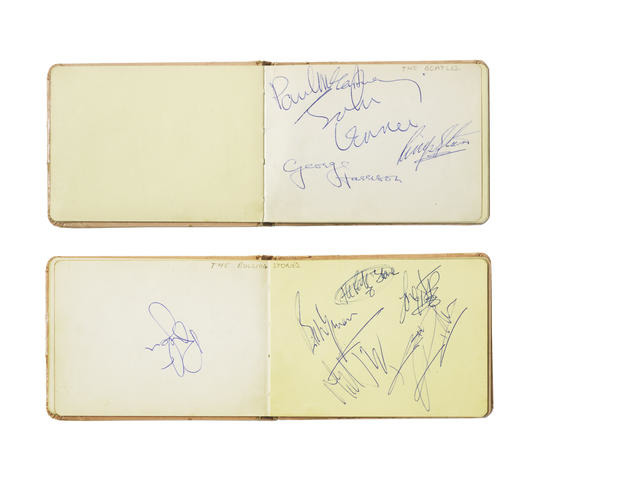

An autograph book is typically a small book (4”x 6” or A6 size) that was small enough to fit into the owner’s hand (or handbag) and could be produced when a celebrity was sited. Some autograph books only have signatures, but others, particularly those kept for signing at parties, often have more interesting contents. This book, up for auction in December 2013 at Bonham’s, has the signatures of all four members of the Beatles:

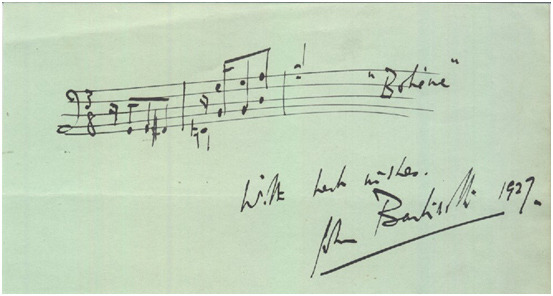

Whereas this leaf is much more interesting:

The English conductor John Barbirolli signed this page in 1927 “With best wishes” and included a bit of music from Puccini’s La bohème. At the time, Barbirolli was just 28 years old and conductor of the British National Opera (which later became the English National Opera).

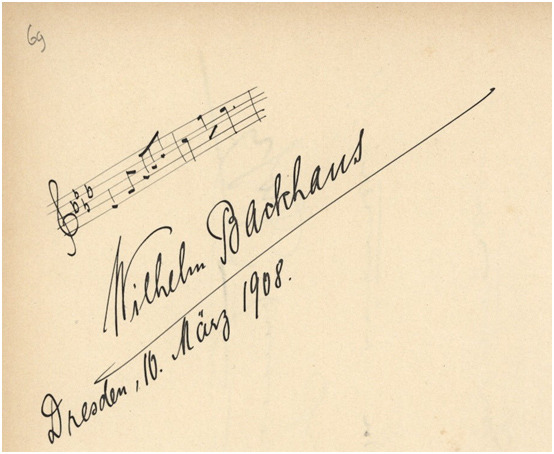

Here’s another leaf, signed by the pianist Wilhelm Backhaus in 1908, which carries a tag from Chopin‘s Ballade in A-flat Major.

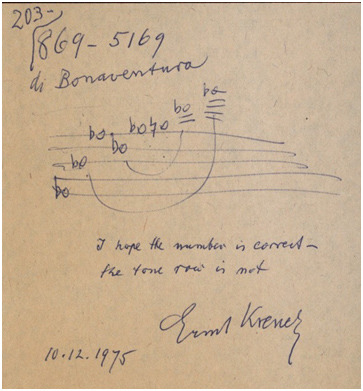

So far, we’ve just seen examples from performers. Composer’s autograph pages can be even more interesting. Here’s one from Austrian composer Ernst Krenek that is addressed to the American conductor Mario de Bonaventura in 1975. The phone number is for somewhere in the state of Connecticut (please don’t phone it – the conductor is no longer at that number) and giving a 7-note tone row (no clef, but e flat, b flat, f flat, d flat, g flat, g natural, d flat, and b flat if read in treble clef). The composer notes “I hope the number is correct – the tone row is not.”

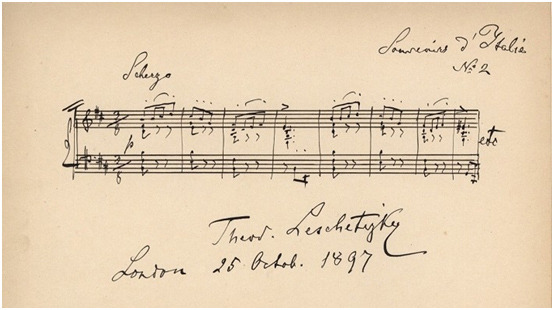

Another album leaf is this beauty from the composer, pianist, and teacher Theodor Leschetizky, dated London 25 October 1897. This gives a selection from the Scherzo from his Souvenirs d’Italie, Op. 39, a piano suite.

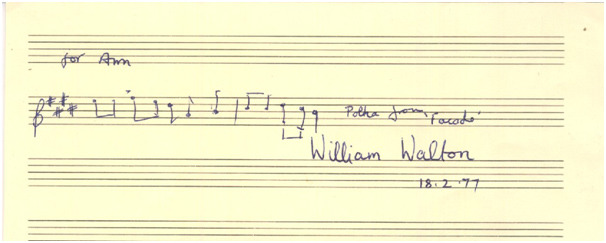

When a formal autograph book wasn’t available, composers often took what was to hand, generally music paper, and made their own album leaves:

This leaf, cut down from a larger piece of music paper, inscribed “for Ann” and signed by William Walton is an excerpt from the “Polka” from his experimental work Façade, which was commissioned by Dame Edith Sitwell. Walton, born in 1902, was 75 in 1977 and the shakiness of his hand writing makes a startling contrast with the strength in some of the other autograph pieces.

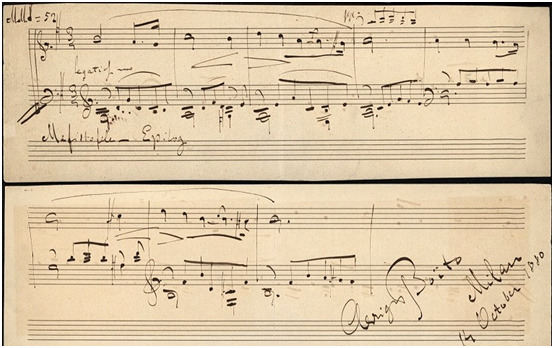

One more autograph is a two-sided autograph, this time from the composer, conductor, and librettist Arrigo Boito. It is also cut down from a sheet of music paper and contains a musical quote from the Epilogue to his opera Mefistofeles, for which he also wrote the libretto. This is from the beginning of the Epilogue, “The Death of Faust.”

These autograph books are an interesting view into what a composer or a performer or a conductor found most interesting. Sometimes these are recent compositions, sometimes these are their most famous piece, and sometimes, it might have been inspired by conversations with the autograph collector. In most cases, we can only guess at why that piece of music might have been included but in every case, it’s an interesting record of the past, passed forward by hand.

All album leaf examples are from the collection of the New York antiquarian music dealer Wurlitzer Bruck.

(C) 2014/2021 by Interlude