by Frances Wilson

3D rendering of Franz Liszt by Hadi Karimi

In fact, he was a remarkable musician and human being. Sure, as a performer he could be flamboyant and extravagant in his gestures, but he helped shape the modern solo piano concert as we know it today and he also brought a great deal of music to the public realm through his transcriptions (he transcribed Beethoven’s symphonies for solo piano, thus making this repertoire accessible to both concert artists and amateur pianists to play at home). He was an advocate of new music and up-and-coming composers and lent his generous support to people like Richard Wagner (who married Liszt’s daughter Cosima).

His piano music combines technical virtuosity and emotional depth. It’s true that some of his output is showy – all virtuosic flourishes for the sake of virtuosity – but his suites such as the Années de Pèlerinage or the Transcendental Etudes, and his transcriptions of Schubert songs demonstrate the absolute apogee of art, poetry, and beauty combined.

Martha Argerich

Martha Argerich

Martha Argerich brings fire and fluency to her interpretations, underpinned by a remarkable technical assuredness. Her 1972 recording of the B-minor Sonata and Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6 is regarded as “legendary”.

Leslie Howard

Leslie Howard

Australian Leslie Howard is the only pianist to have recorded the solo piano music of Liszt, a project which includes some 300 premiere recordings, and he is rightly regarded as a specialist of this repertoire who has brought much of Liszt’s lesser-known music to the fore.

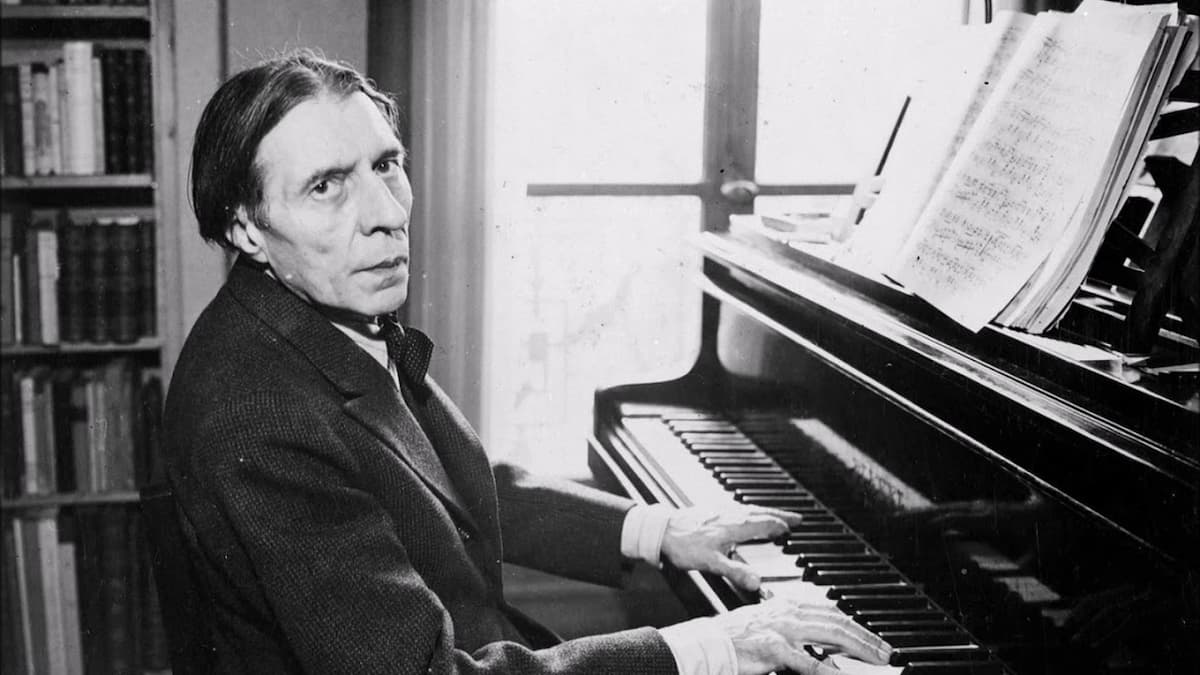

Lazar Berman

Lazar Berman

Berman’s 1977 recording of the Années de Pèlerinage remains the benchmark recording of this repertoire for many. Berman brings sensibility and grandeur, warm-heartedness, and mastery to this remarkable set of pieces.

Alim Beisembayev

Alim Beisembayev

Winner of the 2021 Leeds International Piano Competition, the young Armenian pianist Alim Beisembayev’s debut recording of the complete Transcendental Etudes is remarkable for its spellbinding polish, precision, and musical maturity, all supported by superb technique.

Yuja Wang

Yuja Wang

Yuja Wang has been praised for her breath-taking interpretations of Liszt’s First Piano Concerto which combine force and filigree, emotional depth, and technical mastery to create thrilling and insightful performances.

Springtime – the turning of the season, the weather growing milder and the days longer, the first fresh buds of blossom appearing – is fertile territory for musical inspiration, as this selection of piano pieces inspired by Spring or emblematic of its reveal:

Springtime – the turning of the season, the weather growing milder and the days longer, the first fresh buds of blossom appearing – is fertile territory for musical inspiration, as this selection of piano pieces inspired by Spring or emblematic of its reveal: This piece was written for me as part of a project which paid homage to Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons. 12 pieces were composed for 12 pianists who submitted their own recordings which were then mastered into an album. Although in a minor key, the mood of this piece, with its chirruping, pulsing rhythm and cascading arpeggios in the upper register of the piano, suggests nature bursting into life in all its colourful glory after the gloom of winter.

This piece was written for me as part of a project which paid homage to Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons. 12 pieces were composed for 12 pianists who submitted their own recordings which were then mastered into an album. Although in a minor key, the mood of this piece, with its chirruping, pulsing rhythm and cascading arpeggios in the upper register of the piano, suggests nature bursting into life in all its colourful glory after the gloom of winter.

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.