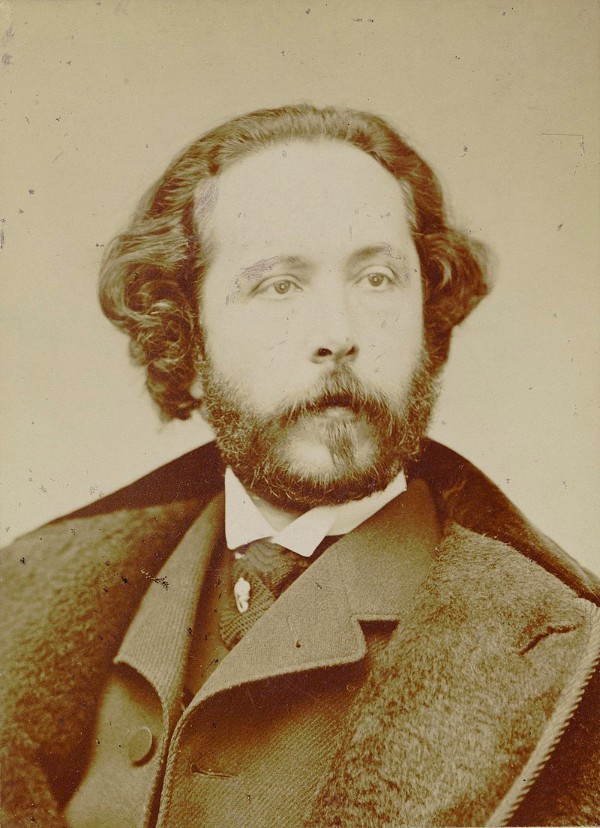

by

Michel Dalberto

In his new album, Dalberto shows us the differing possibilities of virtuosity through the 19th century. He opens with what has become the basic definition of virtuoso: Franz Liszt’s concert paraphrase of a waltz from Gounod’s Faust (S. 407). Starting with the basic theme, Liszt then adds the emphasis and techniques that only he is capable of to create a virtuoso performance.

As a complete change of pace, this is followed by Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 15 in C major, K. 545, which carries the name of the Simple Sonata or Sonata facile. This demonstrates virtuosity in another way: Mozart’s ability to create transparent and seemingly simple work, but which, by its very simplicity, speaks of his virtuosity as a composer.

The next work, Brahms’ Variations on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 35 returns us to the idea of the virtuoso performer, but now matched with a virtuoso composer. Written by Brahms for the virtuoso pianist Carl Tausig, it’s a triple hit, since the original theme was by the violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini. Described variously as ‘fiendish’ and ‘one of the most difficult works in the literature’, and ‘diabolical’. Even Clara Schumann nicknamed them the ‘Witch’s Variations’.

Dalberto plays both books 1 and 2, but joins them in a unique manner. Each book, as written, starts with a statement of Paganini’s theme and then goes into a complete set of 14 variations. Dalberto chooses to play Book 1 through Variation 12, then goes directly to Book 2, Variation 1, skipping the restatement of the theme. This is not unusual, and when the Books are being played back-to-back as they are here, the omission of the restatement of the theme is not unique.

At the end of Book 2, he plays Variation 13, then Variation 13 of Book 1, and closes with Variation 14 from Book 1. He omits Book 2, Variation 14, entirely. He doesn’t explain this decision, but perhaps considers the final Variation of Book 1 a more definitive ending.

Franz Liszt’s Réminiscences de Norma (after Bellini’s opera), S.394, follows, bringing us yet another example of virtuosos creating their own versions of music that everyone knew.

Franz Liszt: Réminiscences de Norma (after Bellini’s opera), S.394

The last virtuoso piece was somewhat of a surprise. We’re familiar with all of Liszt’s versions of Schubert songs, but this is one by Sergei Rachmaninoff. His piano transcription of Wohin? from Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin is a curious amalgam of Schubert’s original song with extra colouration. Rachmaninoff did some 14 transcriptions, ranging from Fritz Kreisler’s Liebesleid and Liebesfreud to Bach’s Violin Partita in E major, but this Schubert work is unique.

The playing is top-notch, if some of the decisions, particularly about the Brahms, are inexplicable. Virtuoso music in the hands of a virtuoso performer is always impressive.

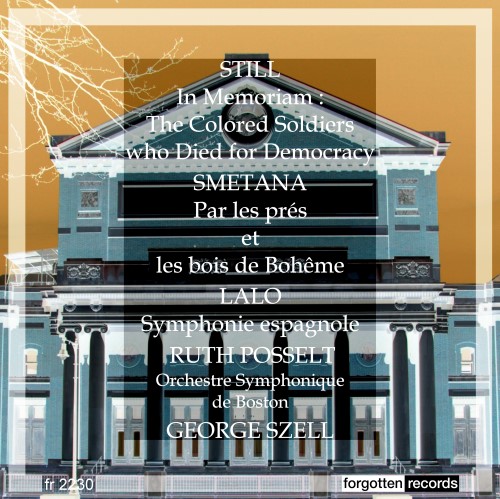

Michel Dalberto: Virtus

La dolce volta LDV148

Release date: 14 March 2025

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter