Are your favourite cartoon characters musical maestros or faking frauds? YouTuber Amosdoll Music explores the animation of the pixelised pianist.

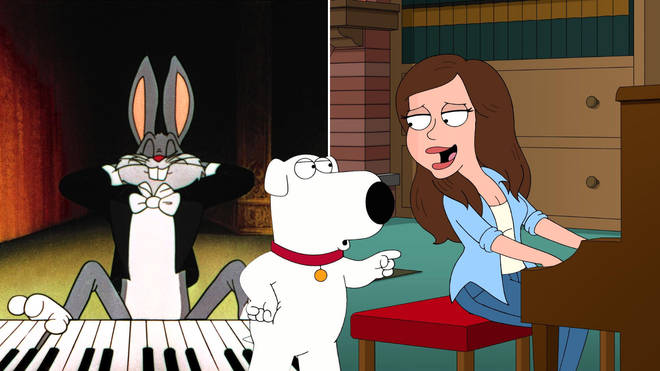

From Bugs Bunny, to Lois Griffin, to various Simpson family members, a piano-playing character is almost a staple in the world’s most famed animations.

But one musical YouTuber has taken a deeper dive into the so-called ‘talents’ of these much loved animations, to see just how accurate their piano-playing is.

Last month, YouTuber started the series, ‘’, on his channel which boasts over two million subscribers. The content creator has since made over 100 videos analysing scenes from shows like Peppa Pig, Looney Tunes, Spongebob Squarepants, The Simpsons, Snoopy, along with various Disney films.

Let’s take a look to see which of our favourite characters might have fallen into the trap of less than accurate animation...

Family Guy

In season 2 episode 20 of Family Guy, created by voice actor and jazz singer, Seth MacFarlane, the protagonist of the show – Peter Griffin – is found out to have virtuosic piano abilities, which can only be accessed when he is extremely drunk.

Peter plays numerous tunes throughout the episode, and his repertoire seems to be firmly ingrained into film and TV show theme songs.

Throughout the 22-minute episode, Peter performs theme songs from Dallas, Nine to Five, The Incredible Hulk, and The X-Files.

But it was his final performance of the Mary Tyler Moore Show theme which intrigued Amosdoll Music enough to make a takedown of Peter’s choice of notes.

Listen above to hear how Peter really played the piece. The reality sounds (perhaps accurately) like a rather drunken performance.

The Simpsons

Bart Simpson may not be the first person you associate from this iconic 33-season-long show with musical talent.

His saxophone-playing younger sister Lisa is the usual culprit, and her talents are often shown off in episodes dedicated almost entirely to her musical abilities.

However, in season 24 episode 20, Bart starts making rapid progress at the piano, shocking his family and friends and making Lisa pretty jealous of her brother’s newfound abilities.

It’s later found out that Bart was actually just miming along to a CD which he had placed under the piano, hence the title of the episode, ‘The Fabulous Faker Boy’.

Eagled-eyed musicians would have been able to tell that Bart was in fact faking from the start due to his pretty noticeable hand (and foot) placements during a rendition of Mozart’s Rondo Alla Turca, which is exactly what Amosdoll Music spies in the clip above.

Tom and Jerry

This 1947 classic stars Tom and Jerry in ‘The Cat Concerto’, a short film which won the Oscar for Best Short Subject: Cartoons.

In the short, animated cat, Tom, performs the opening of ’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2.

Unbeknown to the musical cat however, the animated mouse, Jerry, is rudely awakened from his sleep inside the piano by Tom’s playing. This encounter leads to a host of visual gags as the pair swipe at each other on stage.

While the opening of Tom’s piano performance of the Liszt is near perfect, it’s when the second hand joins in that things start to go awry...

Regardless of the musical mistakes, it was a fantastic feat that the animators managed to get some of the notes right, especially considering that these animations would have been hand-drawn.

Fantasia

Disney’s Fantasia, a musical film released in 2000, takes the viewer on a magical journey incorporating eight pieces of famous classical music.

One of these pieces is George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, a 1924 piano composition that incorporates both classical and jazz influences.

Impressively, this clip which Amosdoll Music has analysed is perfect. The animated pianist plays the difficult music accurately, even with the complex rhythms of the opening riff.

Seeing the notes line up with what you’re listening to really makes all the difference, and the animators must have taken extra time to make sure this was accurate, knowing it would attract a musical audience. Bravo!

Soul (DIsney Pixar)

Another clip found by Amosdoll Music where the animated musician gets it right is this scene from the 2020 Disney Pixar movie, .

This musical adventure film follows the life of a part time school music teacher and jazz pianist, Joe Gardner.

Soul won the Oscar for Best Original Score at 93rd Academy Awards, and it’s easy to see that great care was taken over the representation of jazz musicians in the film. In fact, various jazz greats such as pianist and composer, Herbie Hancock, were consulted as part of the movie’s production process.

What makes this scene so special is Gardner’s description of each part of what he is playing; “then he adds the inner voices, and it’s like he’s singing!”

Stick with the familiar and play the music you learnt before

Stick with the familiar and play the music you learnt before